On April 5, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) capped off a nearly year-long project to change the name of Dixie Place to Vivien Thomas Way.

Running from 21st Avenue South to VUMC’s Central Garage, the street honors the life of Vivien Thomas, an African-American lab technician who worked at VUMC from 1930 to 1940 and developed a novel procedure for the “blue baby” surgical operation.

Roots of Change

The idea for changing the name of Dixie Place originated from the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, per second-year medical student Alex Lupi, one of the leaders behind the name change. Lupi said that after seeing posts about Floyd’s death circulate on social media, he and his classmates felt a desire to take action.

“A bunch of students wanted to protest,” Lupi said. “There was a lot of talk around activism and what you can do as a medical student.”

During a meeting with then-first-year medical students, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM) Faculty Mentor Dr. Walter Clair responded to students’ desires to invoke change by presenting the idea of changing the name of Dixie Place. Clair encouraged students to take action and expressed his personal frustrations with the Confederate symbol.

“One [humiliation] that I regularly suffer is turning into Vanderbilt’s campus on Dixie Place. If you guys want to do something that would certainly have meaning to me and would be long lasting, do something about the name of that street,” Clair said.

After Clair’s call to action, nine first-year medical students—including Lupi and Ekiomoado Olumese, who spoke at the April 5 event—emailed Clair to form an ad hoc committee of students pushing for the change of Dixie Place. Clair served as the committee’s faculty leader, and the team met for the first time in June 2020.

Name Selection Process

The students on the committee recognized that their voices should not be the only ones represented in the name change of Dixie Place. In the renaming process, Lupi stated that he and his teammates sought to incorporate the perspectives of many different members of the VUMC community, reflecting the ideals of community and inclusivity that inspired the initiative.

The committee reached out to Vanderbilt University and VUMC Chief Diversity Officer Dr. André Churchwell, proposing a collaboration across several different VUMC employee resource groups (ERGs), or affinity groups. Churchwell brought together representatives from African-American, Latinx, Perspectives, Resources, Insights and Direction by Employees (P.R.I.D.E.) and Veteran ERGs, along with Minority Housestaff for Academic and Medical Achievement representatives and VUSM and VUMC administrators. Representatives from the different groups met over Zoom to discuss the history of Dixie Place, the aspirational values of the new sign and the strategic approach to implementing the physical signage change.

“It took a while because it was a very diverse group of folks to get together and do research on how that sign got there in the first place, how would we go about the process of vetting names and eventually, when we chose a name, who would be part of the process to then change it,” Churchwell said.

Per Lupi, during their first series of meetings, the group identified values to be reflected in the new street name. Lupi added that the group originally considered both symbols and names of specific people to use as the new name.

“We came up with a list of ideals that we wanted to meet—perseverance through adversity, loyalty, ties to Nashville or Tennessee in general,” Lupi said. “One really big one was being the antithesis of Dixie.”

According to Clair, the students, faculty and ERGs researched and brainstormed potential historic and contemporary figures to highlight in the street name. Then, Clair said that the group recongregated and narrowed down the list of candidates to five finalists. Per Clair, the selection process allowed all members of the ad hoc committee to deepen their understanding of Vanderbilt, medical and civil rights history.

“We talked about the pros and cons, who we would represent and why,” Clair said. “We were all learning about people that we otherwise would not have learned about.”

VUSM students on the committee, including Lupi and Olumese, compiled presentations on the five finalists and pitched the names to a panel including Clair, Churchwell and VUMC Chief Operating Officer Dr. John Manning. The panel selected Vivien Thomas to be honored on the street sign, kicking off an implementation process that included receiving the Metro Nashville City Council’s approval of the name change on Dec. 1.

Vivien Thomas

Born in 1910 in Lake Providence, Louisiana, Thomas joined Dr. Alfred Blalock’s laboratory at VUMC as a technician in 1930, just one year after graduating from Pearl High School in Nashville. Thomas quickly began to collaborate with Blalock on experimental techniques for vascular and cardiac surgery.

Despite Thomas’s mastery of research methodologies and collaboration with Blalock, Thomas was classified and paid as a janitor at VUMC, limiting the accreditation and documentation of Thomas’s scientific contributions. After Blalock left VUMC in 1940, he decided to continue his research at Johns Hopkins because the hospital allowed him to include Thomas on his staff, per Clair.

“A lot of people don’t know that Blalock turned down a job at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit because he insisted that wherever he went, he was gonna take Vivien Thomas with him,” Clair said. “They said ‘We don’t hire African-Americans in our hospital,’ and he said ‘Then I won’t be coming to Henry Ford Hospital.’”

At Johns Hopkins, Thomas innovated a novel surgical solution for cyanosis—or “blue baby” condition—while operating on dogs. Per his biography on VUMC’s website, Thomas coached Blalock through the first performance of the procedure on a human in 1944, and the technique was published in the May 1945 edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association as the “Blalock-Taussig shunt,” with Thomas receiving no credit.

Churchwell and Clair said that the perseverance reflected in Thomas’s story and his background as a Nashville native motivated the selection panel to honor Thomas in the new street name.

“He is representative of an African-American Nashville native who grew up in the Jim Crow time of Nashville,” Churchwell said. “He succeeded against impossible odds.”

Clair emphasized that, despite the constraints imposed by racism, Thomas demonstrated “excellence in the face of adversity,” succeeding as a scientist, surgical pioneer and mentor.

“Vivien Thomas put up with a lot of racism, but he continued to pursue science through whatever avenue was available to him,” Clair said. “He taught a lot of people. A lot of surgeons were trained by him, including Blalock.”

Impact

Lupi, Clair and Churchwell said that they believe the sign change will help make Vanderbilt a more inclusive community. In addition to serving as a reminder of the Confederacy for VUMC faculty and staff, according to Clair, Dixie Place was one of the first markers of campus for visiting VUMC patients. Clair said that patients would inevitably interact with Dixie Place because of its proximity to the hospital’s 21st Avenue entrance.

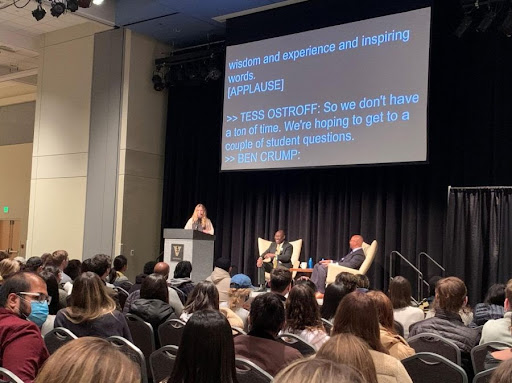

The renaming of Dixie Place to Vivien Thomas Way also brings attention to an influential person overlooked by mainstream historical narratives, according to Clair and Churchwell. During the April 5 celebration event, Churchwell expressed hope that “anyone with an ounce of curiosity” will see Vivien Thomas Way and research Thomas’s story, educating themselves on someone whose historical contributions have been masked by systemic racism.

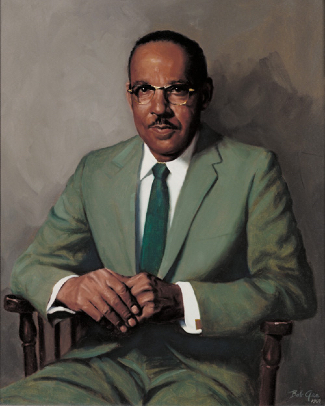

Vivien Thomas Way’s purpose of uncovering the contributions of neglected historical figures coincides with Churchwell’s Hidden VUMC Figures project. Hidden VUMC Figures began in 2017 and honors “unsung heroes” each year for their work in uplifting the VUMC community, including nurses, technicians, research assistants and communications officials.

Churchwell and the VUMC Office for Diversity Affairs have also constructed a “VUMC Diversity Timeline” permanently on display in Light Hall. The timeline maps the historic contributions of marginalized individuals at

VUMC since 1904. Additionally, the Office for Diversity Affairs honors historically overlooked figures—including Vivien Thomas—in the Underrepresented Groups Portrait Series.

“I’m sure that if most hospitals, medical institutions and universities start digging, they’ll find those key staff folks who contributed to the growth and magnificence of their medical center,” Churchwell said.

Jerry Kaz • Sep 20, 2021 at 12:09 pm CDT

I have no problems with finding ways to honor people with the accomplishments of Vivien Thomas. I do have problem with the article that leaves the reader with misinformation by leaving out facts.

The article leaves the reader with the notion that the renaming is for the purpose of correcting a wrong of racism that is behind any use of the name Dixie. It does this by not mentioning the origin of the name Dixie Place. The name Dixie Place was not recognizing a period of time but honoring Dr. Richard Douglas that was nicknamed Dixie by his father. He went through life known as Dixie.

Who is Dixie Douglas? Check out a WSJ article at https://www.wsj.com/articles/vanderbilt-medical-school-renaming-dixie-street-history-11631913014. Born in 1860, he was a pioneer in medicine. He pioneered surgical techniques and promoting cleanliness that greatly reduced infections. His negotiations with University of Nashville and Vanderbilt University basically helped establish Vanderbilt’s shining achievement the Vanderbilt School of Medicine.

Vivien Thomas Way is a great honor to a person worthy of the honor. The renaming is also an insult to the memory of Dr Richard “Dixie” Douglas, his achievements, his family and Vanderbilt University. Douglas Way would have been a better way to still honor a great man and remove the word Dixie. Educating people that this was a person rather than a racial slur would have been even better. At the least a journalist should give facts rather than leave obvious innuendos as to the reason the name was changed.

Ed Engbrock • Sep 20, 2021 at 4:28 pm CDT

Correctamundo! Selective omission of otherwise substantive facts that don’t support the popular narrative – media bias regaled in all of its collegiate finery! This budding reporter would make a splendid addition as a staffwriter at the NYT, WP or many other once-reliable fishwraps…