The Metropolitan Council of Nashville and Davidson County (Metro Council) passed BL 2021-961 on Feb. 1 with a 22-14 vote, approving a six-month pilot program for the implementation of license plate readers (LPRs).

Authored by District 26 Council Member Courtney Johnston, the bill was passed after over 15 months of deliberations.

“I was inspired to write this bill by fears that my residents have about drive-by shootings and murders happening in their own neighborhood, blatant drug deals and generally unsafe activity that makes them feel uncomfortable in their own yards and own porches,” Johnston said.

Per Johnston, the bill was written with assistance from the ACLU, the Policing Project at New York University Law School and Vanderbilt Law School professor Christopher Slobogin. Slobogin is working on a research grant with several other Vanderbilt professors studying the effectiveness of automated LPR technology.

“I’m glad it’s a pilot program to get a sense of whether it works well in Nashville and then, at that point, decide whether to do it permanently,” Slobogin said. “It could be a significant boon to law enforcement, specifically in solving and deterring serious crimes.”

The bill allows Nashville and Davidson County to acquire LPR technology, which are automated cameras that take pictures of passing cars’ license plates, and run them against “hot lists.” These lists can include license plates of stolen vehicles or vehicles that have been used in a crime.

Many of Davidson County’s neighboring municipalities have already approved the use of LPRs, including in Brentwood, Belle Meade and Mt. Juliet. According to a 2013 report from the U.S. Department of Justice, 75% of nationwide police departments in municipalities with over 100,000 residents use LPR technology.

Although Metro Council passed the LPR bill in early February, Nashville residents will not be seeing the cameras any time soon. Both Johnston and At-Large Metro Council Member Bob Mendes said that the installation timeline is undetermined and that it could be up to two or three months before any LPR technology is actually implemented.

Per a 2017 measure passed by the Council, all acquisitions of surveillance technology must first undergo approval from the Council and a public hearing. The city has to find an LPR vendor and finalize a contract before seeking final approval. No date has yet been set for the LPR hearing.

Provisions of bill

Under Tennessee state law, police departments have been allowed to utilize automated LPR systems since 2014, although the implementation of LPR technology is delegated to each municipality. In 2017, a bill passed by the Metro Council prohibited the use of LPRs on public roads. However, under the new law, the 2017 law is no longer in effect.

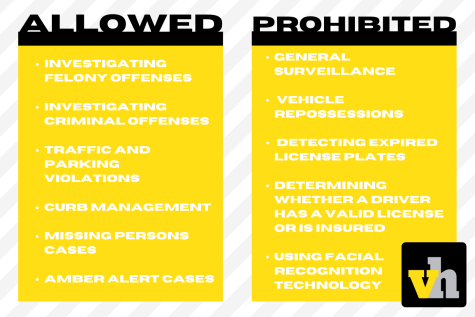

The bill reads that the LPR systems will only be used for investigating felony and criminal offenses, traffic and parking violations, “smart parking,” curb management, missing person cases and Amber Alert cases. The bill explicitly prohibits the use of LPRs for general surveillance, vehicle repossessions, detecting expired license plates or determining whether a driver has a valid license or is insured. It also prohibits the LPR system from utilizing facial recognition technology.

The bill also specifies that all data collected by the LPR devices must be automatically deleted 10 days after collection, provided that it is not being used in an ongoing investigation. Johnston said this 10 day retention period is much shorter than the length prescribed by Tennessee state law, which is 90 days, and much shorter than those of other cities, such as New York City, which retains LPR data for five years. Per Slobogin, these provisions were included to limit civil liberties concerns in relation to the bill.

“We wanted to limit the retention of records and the purposes of their use,” Slobogin said.

Community support

Some supporters of LPRs claim that the technology is useful for solving and deterring crime. In a letter sent to the Metro Council on Jan. 31, Metropolitan Nashville Police Department (MNPD) Chief John Drake cited several past cases in which LPRs assisted police departments across the country. The Belle Meade police department told WSMV in a 2020 article that, since implementing LPRs, they have been able to find two to three stolen vehicles per month, in contrast to one per year before using LPRs.

When developing the bill, Johnston said she consulted communities that have already implemented LPRs.

“I talked to police and they say that LPRs are a force multiplier, the most effective tool that they have,” Johnston said.

However, as Slobogin emphasized, research on the effectiveness of LPRs is still relatively limited and inconclusive. A 2018 study by the International Association of Chiefs of Police found that mobile LPRs (cameras attached to police cars) were 140% more effective at detecting stolen vehicles than vehicles without the technology, and it found fixed LPR cameras to work better than these mobile units. The same study also found a 35% error rate for hits in the LPR system due to a license plate misread. A 2011 study in the Journal of Experimental Criminology found no statistically significant deterrence of crime through the use of LPRs.

“Some research suggests it is not useful, but it still collects data of thousands of cars every day, especially when balanced against a lack of data on crime prevention,” Slobogin said.

Community backlash

Some opponents of LPRs say that the technology is a violation of civil liberties. They point to violent police encounters, especially against minority groups, that could occur due to errors in the system. A coalition of many Nashville affinity groups, including the Nashville chapter of the National Association for the Advance of Colored People (NAACP), Black Lives Matter Nashville and the Tennessee American Muslim Advisory Council opposed the LPR measure in fear that minority groups will be disproportionately targeted by the technology.

Mendes opposed the LPR pilot program, voicing many of his concerns in an annotated version of the bill’s text, which he released leading up to the vote.

“My biggest thing is that when this goes wrong, when there are mistakes with license plate reader technology, innocent people get surrounded by multiple police cars and pulled out,” Mendes said. “Some council members feel like, ‘mistakes will happen.’ But when we’re talking about mistakes leading to infringing on civil liberties, I’m not that eager to tolerate very many.”

A 2015 analysis of raw LPR data from the Oakland Police Department found that mobile LPRs tended to collect a disproportionate amount of data from low-income, Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

To combat potentially biased targeting of Nashville’s underprivileged communities, Johnston said the cameras will not collect racial or ethnic data. According to the bill, police officers conducting a stop from LPR data may collect their own report including the race and ethnicity of the driver but only “if voluntarily provided by the driver at the request of the officer.”

Johnston also noted that the fixed LPR cameras will only be placed on major roads and be equally distributed throughout all four quadrants of the city.

“You may pass a camera at Harding Place and Trousdale by 65, but that isn’t going to tell you anything. It’s impossible to track someone that way,” Johnston said.

Local organizations, including Worker’s Dignity, which partners with Nashville’s sizable immigrant worker population, also raised concerns that LPR data may be shared with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“Worker’s Dignity serves primarily immigrant workers in south Nashville, which has a very large Hispanic community who have historically been targeted by ICE,” senior Matty Templeton, who works for Worker’s Dignity, said. “One of the provisions in the bill is that license plate information can be basically turned over to ICE at any time for pretty much any reason.”

However, Drake’s letter to Metro Council states that MNPD would not share LPR data with ICE.

In his annotated bill, Mendes specifically disagreed with how the bill stipulates the limits of the sharing of Davidson County LPR data with other law enforcement agencies “[t]o the extent consistent with state or federal law.”

“The state of Tennessee has passed very aggressive anti-sanctuary city legislation,” Mendes said.“There’s no question that, if ICE were to ask Metro for its license plate reader data, Metro would have to give it to them under state law.”

Mendes is working to amend the text of the bill to further limit the expansiveness of LPR technology. He filed three amendments at a Feb. 15 Metro Council meeting, one of which explicitly prohibits LPR data from being shared with ICE. He noted that, despite the efforts of this amendment, it is not clear if a city ordinance can legally prevent a federal agency such as ICE from obtaining LPR data.