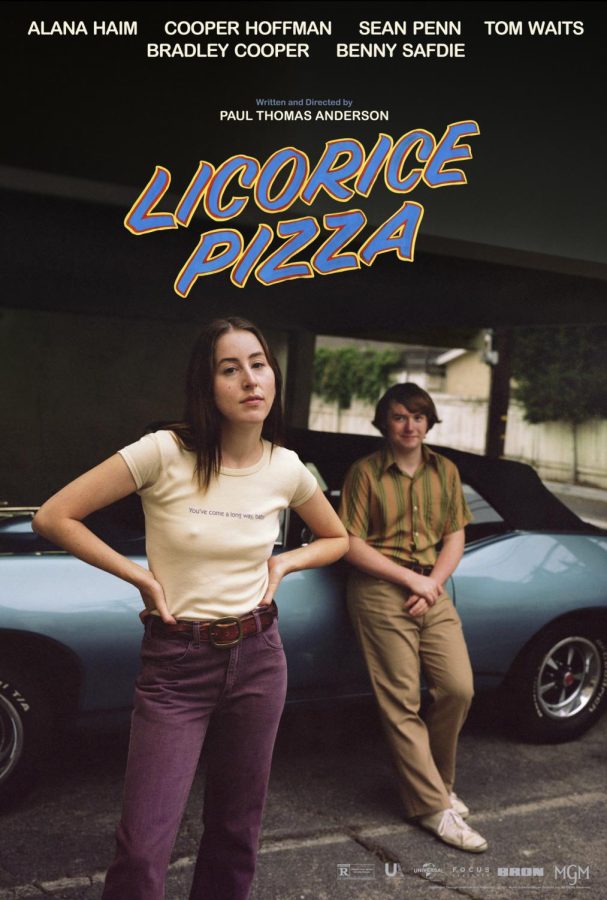

“Licorice Pizza” is a tale as old as time: the 15-year-old child actor/entrepreneur meets the 25-year-old yearbook photographer who has no idea what to do with her life, and they fall in love.

Actually, it’s a tale that’s been told exactly zero times and will probably never be told again, but that didn’t stop director Paul Thomas Anderson from spending more than two hours desperately trying to convince us of its endearing realism and enduring relatability. The sad truth, though, is that “Licorice Pizza” isn’t a love story we’ve all experienced. Instead, it’s the story of the weirdest guy you know meeting the weirdest girl you know, and somehow, they end up together. Like those high schoolers who’d wear cat ears to school and make out in the hallway. You know the ones.

Defying all odds, this weirdness isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as the film has a ton of heart. The question remains: whose heart exactly is that? I spoke with lead actress Alana Haim to find out.

Instinctively, my answer to this question would be Haim herself, as the character she plays is also named Alana and the two have a ton in common. I instantly got a sense of their similarities when she enthusiastically joined the Zoom call with her name listed as “baby Haim.”

“The thing that I loved about her the most, and I definitely am the same way, is that she’s incredibly protective over the people that she loves,” Haim said of character Alana Kane. “She’s a little crazy—I’m not as crazy as Alana Kane—but she rides for her friends and her family. I see myself in that.”

Additionally, both Alana Haim and Alana Kane grew up in the San Fernando Valley, which Haim said helped her make Kane feel more real. It even led to some bonding moments with her co-star Cooper Hoffman, who plays her love interest Gary Valentine.

“I knew every reference that Paul [Thomas Anderson] had given me,” Haim said. “Cooper is from New York, so he had a lot of Valley lingo, but I remember sitting with him with a map and being like, ‘this is Ventura, this is … ’ and going through all the different streets so he could become a Valley kid. I’m a Valley girl through and through.”

Haim also elaborated on the various ways she immersed herself in 70s vibes to make Alana Kane feel more genuine—which included learning to drive stick shift, filming nuclear family scenes with her real-life parents and sisters and waking up at 5 a.m. every morning to do her own hair and makeup.

“We basically lived in the 70s all the time. No one had phones. I would get to set, and it was like we were in this different world,” she said. “It’s an era that I’ve always loved and been inspired by.”

Of course, this early call time involved a lot of “screaming into a hairbrush” to classic 70s hits like Freda Payne’s “Band of Gold,” which Haim described as Alana Kane’s “mantra of life.” This meant the music of the 70s played a large role in helping Haim channel the spirit of the decade.

“The songs that are in ‘Licorice Pizza’ are all songs that I love so much,” Haim said. “When we got to the pinball palace, between takes, Paul would play music so it actually did kinda feel like we were all at a party in this pinball palace. Music was constantly playing, and it kept the vibe going.”

Whether it was in the pinball palace or other on-site filming locations, Haim repeatedly emphasized how enjoyable it was just spending time with the cast and crew.

“Being at the Tail of the Cock […] was like the first time I had been in a restaurant in a really long time. It felt so nice to be in a restaurant; everyone had fake martinis and we were just having a really good time,” Haim said. “There was a pianist that would play club music between takes, so it actually felt like we were all having dinner together for a full week. It was just as fun as it looked.”

Post-evaluation, it’s clear Haim’s—and Anderson’s—hearts were fully invested in “Licorice Pizza,” but something is still missing. By default, most films are in the business of making fictional stories seem real, so the fictional characters likely don’t exist in real life. In spite of this general rule, the film’s conspicuous lack seems to be the absence of a real Alana Kane. “Licorice Pizza” is presented like a movie based on a true story, and I walked out of the theater wanting to hightail it to Kane’s Wikipedia page to find out what she’s up to today. But there is no true story. Haim delivers a wonderfully convincing performance, but it’s a performance of a personality that was created in a lab, retrofitted onto a character that’s too human to exist at all.

Maybe someone who grew up in the Valley in the 70s would be swooning over Alana Kane’s aimless authenticity. Sadly, though, I just couldn’t bring myself to get fully behind the character, despite Haim’s excellence on screen. Let’s turn to Gary to investigate further.

Elephant in the room: he’s 10 years younger than Alana, which isn’t really relevant if you grit your teeth and pretend he’s not a minor—but it’s still weird, despite its irrelevance to the story. The fact that we’re expected to just choose to ignore it is the first red flag.

The second, third and fourth warning signs are smaller: a weird scene where he gets mad that Alana won’t show him her boobs, the ugly white suit he wears in the final scenes or—the most unusual of the three—the fact that he somehow knows more people in town than an AKPsi networker.

But red flag number five is a doozy: his affinity—or maybe Anderson’s—for manufactured emotional cruces. The movie presents its climax as a series of three scenes: one in which Alana runs after Gary during a moment of crisis, one in which the roles are reversed and a third in which the two emotionally damaged kids (again, Alana is 25) run toward each other across town, intercut with moments from the first two running sequences.

These scenes are pretty without a doubt. But we don’t care enough about Alana and Gary for them to be beautiful. The climax is supposed to give us a sense of the ineffable, but anxious flute notes and drums turn it into a faux nature documentary instead. We’re no longer watching a rom-com; we’re observing these “specimens” in their natural environment, California in the 70s. And once we’re on this thread, it reminds us of another scene where the two of them breathe loudly into the phone to each other, almost like we’re watching something gross from behind a one-way mirror. We want to turn away, but we can’t.

Let’s spin that thread to its logical conclusion. Haim and Hoffman do have great chemistry, so their scenes together feel like two friends just talking, but a bunch of these spliced together cannot carry a two-hour movie. Each one individually is like a detailed scene study designed by someone in a pretentious film school to exist only in a vacuum, without the consideration that they’d eventually have to come together to form a full-length film.

In the end, Gary Valentine and Alana Kane feel authentic. But they feel sterile.

Haim almost changed my mind with a beautifully worded evaluation of the central philosophy, the emotional message, behind the film.

“The thing that still is mind-blowing to me is, honestly, how many people do you meet on a daily basis?” Haim said, pausing in her Zoom window for dramatic effect. “And you never know who’s gonna stick. You never know who’s gonna come back into your life, stay in your life. Alana could’ve met Gary and it could’ve been a 5-minute conversation and they never see each other again, and their lives go on, whatever. These two people meet, and they don’t know it yet, but their lives are forever changed, and they go on these crazy adventures. And,” she said, bringing it back to her real life, “I think about that with Paul and with Cooper.”

Another dramatic pause—for us to think about those people in our own lives.

“It’s wild when you look back on your life, and you’re like, ‘oh yeah, never thought that person would stay,’ and now they’re just here still. And I’m so happy for it, and they make my life so rich and happy,” Haim said. “That definitely is how I feel with Gary and Alana.”

Two weird characters doing weird things and falling in weird love; this is “Licorice Pizza.” I’m weird too, so I enjoyed it, but not enough to make me want to become any weirder.

“Licorice Pizza” is now showing at the Belcourt Theatre.