I was having a bad week.

Between back-to-back final exams, packing for my move to the U.S. and completing paperwork and visa interviews, I felt like I was drowning trying to get my life in order. I was receiving emails from Vanderbilt reminding me of important dates, items to bring to school and events I could — and probably should — attend. My inbox was flooded with messages from the university about adjusting to college academics and connecting with my future peers.

Every single one of these emails started and ended with the same sign-off: “Enjoy your summer break!”

All the way across the ocean, I was overwhelmed and anxious about my upcoming move. I was frustrated that this sign-off didn’t seem to apply to me at all. I never really got a break after high school to relax and refresh before launching into my first year at Vanderbilt.

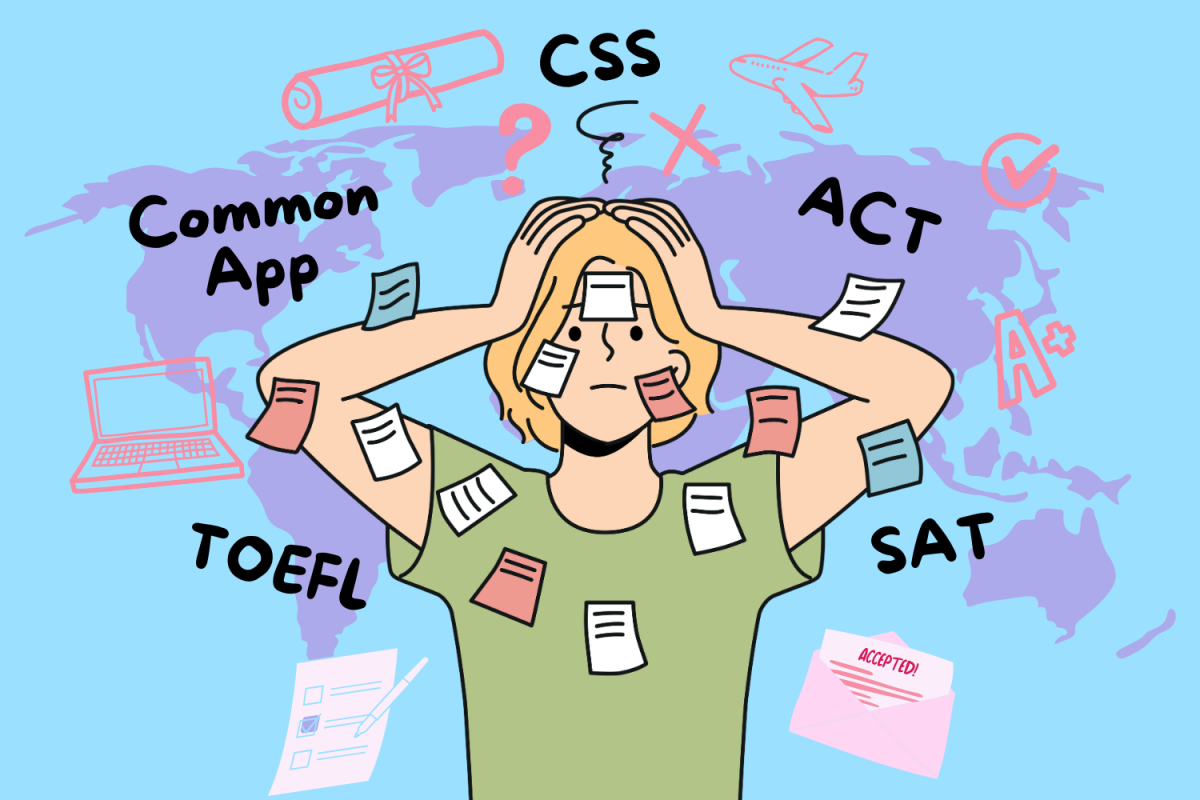

As an international student, I am not alone in having such a stressful transition. Applying to American colleges can be extremely difficult for students in some countries — particularly in Bangladesh where I am from. We don’t have the same grading system as the U.S., which often means we have to adapt our transcripts and test scores to conform with American standards. Our subjects differ both in content and assessment, so I had to spend hours with my teachers and school officials to add explanatory notes to the bottom of my transcript and on my Common Application.

The SAT poses another burden. Taking an intense examination that assesses complex English literary devices and detailed grammar puts those of us who learned English as a second language at a disadvantage. In contrast to the myriad of test-prep companies and SAT-prep books stocked on bookstore shelves in the U.S., international students often have to rely solely on YouTube videos. The costs of purchasing and international shipping for test-prep resources can also be a barrier.

I believe American universities could address this discrepancy by accepting scores from international board exams, which we are already required to take, or going test-optional. While it is important for schools to verify that potential students will be able to succeed in a fast-paced, English-speaking environment, there is a difference between being able to read and understand textbooks, engage in fluent and stimulating academic debate and take exams versus dissecting confusing SAT passages about ancient art. The recent move to test-optional admissions by some American universities is a good start in ensuring international students have more equitable access to the admissions process.

Vanderbilt currently offers placement exams in English and languages, but not in STEM subjects like math, chemistry or biology. AP courses are not offered internationally. International students interested in studying STEM like myself are put at a disadvantage as we have no way to prove that we already know introductory content. American universities accept AP exams that cover the same course material as our international board exams, but these scores are not accepted. As a result of not having AP classes and not having the ability to transfer credits from our national board exams, students are forced to retake classes at Vanderbilt rather than taking a fun, new course or pursuing high-level courses for our majors. For example, I had to take the Calc 1300 and 1301 although I had already studied and given exams on these same contents and this is the same scenario for General Chemistry and General Biology. Accepting international board exam equivalents would help students like me be more able to pursue a career in physics or medicine. Another option would be to offer subject-specific placement exams that would allow students who have already taken rigorous science classes in their home countries to take the appropriate level courses.

In the U.S., high school summer break typically takes place from June to August and is meant to rejuvenate students’ minds and clear their heads. In the Eastern world, however, you will find that students are investing a significant amount of time getting a head start on next year’s assignments, learning how to apply to colleges in a foreign country and navigating the bureaucracy associated with a confusing international move. During this time, we are studying for our final board exams as well as organizing our visa paperwork, not to mention packing to move across the world. In South Asia especially, this break isn’t even considered a “break;” it is instead a standard hiatus from classes filled with work.

Like many other students, I was ecstatic when I got my Vanderbilt decision last December. Unfortunately, my excitement didn’t last for long. Over the next eight months, I had to prepare documents and paperwork for my visa and embassy interviews, which includes submitting my I20, DS-160 and SEVIS fees — if you’re confused about what all these numbers and letters mean, imagine how I felt. I also struggled to figure out how to make foreign transactions. I was jealous that some American students had gotten the opportunity to visit Nashville and learn about Vanderbilt’s culture and ambiance first-hand before move-in day. Domestic applicants have a unique opportunity to gauge the environment and “vibe” of their potential future home rather than relying on pictures on campus websites. Meanwhile, I was terrified to leave my home and family halfway across the world. I wished I had a family friend, older cousin, or another contact who had gone to Vanderbilt that I could turn to with questions and fears.

For many international students, it is hard to reach out to others you do not know or share a language with. While domestic students have families with knowledge of the college admissions process or experience, international students can feel alone and out of their depth. I was lucky enough to meet some Bangladeshi sophomores who went above and beyond to help me out with my transition. In reality, not all students have that opportunity. Without these now-friends, I would be lost in regard to U.S. culture, environment, curriculum and everything about life and school here.

International students are new to the culture, environment, curriculum and everything about life and school in the United States. Making this shift is much more difficult for international students, who are trying to balance making friends, assimilating and understanding cultural differences. There are many social customs, quirks of the English language and American niceties that international students have not encountered. How can we ensure all international students have this support?

Each international student at Vanderbilt is assigned to an International Student Scholar Services counselor. Although these counselors are kind and well-intentioned, they are not students and, therefore, cannot adequately relate to us and our unique circumstances. Moreover, ISSS is primarily responsible for assistance related to matters like visa applications and various other government paperwork; yet, they are not obliged to thoroughly check these documents. The office provides international students with little guidance on how to prepare for Vanderbilt and the transition to a new culture and country.

So what can we do as students, faculty and staff to ensure that international students enter Vanderbilt well-prepared? For starters, International Student Orientation should be revamped to be more engaging and informative. Most of the information these programs covered was reflected in the many documents and materials Vanderbilt provides incoming international students. Orientation should instead be geared toward how international students can make friends and find others with similar experiences.

In addition, being connected to VUceptors — who serve as faculty and peer mentors to first-year students — as soon as possible would make the transition more bearable. I had a wonderful experience with the VUcept program and enjoyed the productive and stress-relieving meetings every week; having access to this outlet and these connections earlier would have been beneficial.

I hope that future international students will be better equipped to have a smooth, inclusive transition to Vanderbilt. While tedious paperwork and social and cultural barriers are here to stay, there can definitely be additional support and resources for international students. Something as simple as assigning international students a personal mentor or an upperclassman from a similar region to serve as a mentor would go a long way toward making them feel welcome.

Although my experience transitioning to higher education in the U.S. was difficult, it is important for international students to narrate shared experiences and stories so we can get the resources we need. My story is more than simply a lamentation of how international students never get a break; it is part of greater concern for the lack of robust support for international students at Vanderbilt and many other universities.