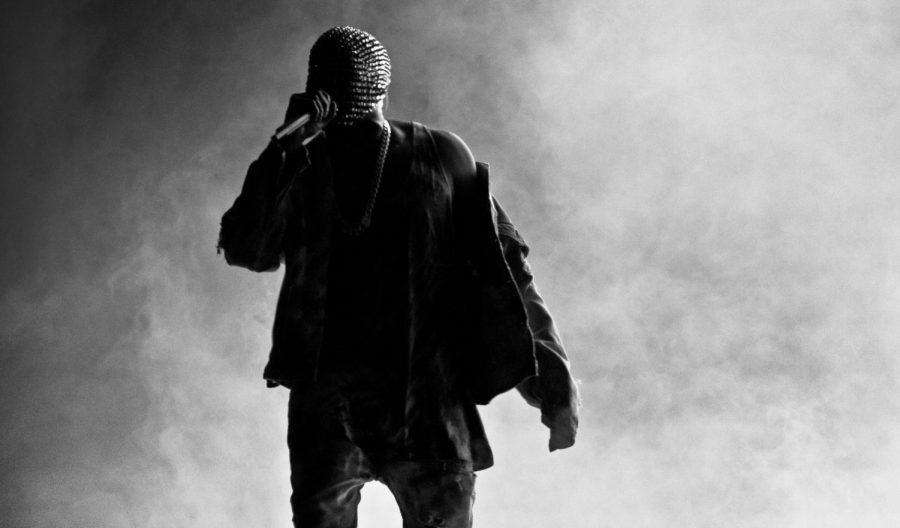

One of the most widely-shared snippets from Ye’s 2022 Netflix documentary “Jeen-Yuhs” sees the rapper, an upstart, peasy-haired geek no older than 20, playing “All Falls Down” for a room full of uninterested Roc-A-Fella Records executives. It offers a jarring look at what incredible grit it took not only Ye, but an entire generation of fellow aspiring artists who made it—and didn’t make it—to grasp even the measly beginnings of solo careers.

Gen-X entertainment industry success stories are rife with crumpled notes slipped underneath big-name doors, early-morning buses into bustling cities and overarching high-risk-high-reward motifs. There was no internet to carry your mixtape to an office in Los Angeles for you, so you had to do it yourself. Such a construct necessitates some level of radical passion; why would you brave a tricky hitchhiking journey from your suburb in Montana to Hollywood if you weren’t absolutely sure the mixtape in your carry-on bag was going to take you into the rest of your life? Making it in the 20th Century required betting on yourself. And with little to fall back on, there was a lot to lose.

Around two decades have passed since Roc-A-Fella’s front desk people brushed off one of the greatest hip-hop songs of all time, and today, Ye finds himself as the entity being appealed to by younger artists. But not in the sense that he has retired from music and accepted an A&R role at a major label—now, the casting free-for-all has migrated from the office and landed in his Instagram comments section.

This past winter, Ye took the drastic measure of following about 7,000 accounts seemingly at random. The move, as unprecedented as it was unexplained, empowered many unsuspecting characters to carry themselves as if they were “in” on Ye’s cryptic masterplan, as if they’d seen his vision eye-to-eye and finally landed their official endorsements. One such figure is New Jersey-bred musician ProdByZaqq (real name unknown), who produces mediocre rap songs for “audiences” who may very likely be Instagram bots. Since Ye began his anti- “Skete”-Davidson tirade on the app a few weeks ago, ProdbyZaqq has been a familiar annoyance, flooding the comment sections with overly-laudatory messages that have quickly grown corny, and using his blue check to make these tactics hyper-visible. If you throw the query “Prodbyzaqq” into Twitter’s search bar, the first tweets to pop up include “whoever prodbyzaqq is may God take his life,” “the devil works hard, but prodbyzaqq works harder” and “I have information that will lead to Prodbyzaqq’s arrest.”

Where ProdbyZaqq’s story goes beyond Instagram comment trolling, yet, is in the gall of his latest move: this past week, he named a song after his most notorious spam message—“Ye the (goat emoji) No (cap emoji)”—and uploaded it to YouTube. It is, much like the rest of his music, unspeakably repulsive. Hearing the song feels a lot like what hardworking parents must go through when their son, who quit his job to focus on rap, decides to play a few painful selections at Thanksgiving dinner.

But what the track lacks in listenability, its ethos makes up for in cultural futurism. With every last annoying comment, ProdbyZaqq is showing us that in the internet era, two very vital things no longer need to be at the foundation of time spent in the limelight: (1) cross-country hitchhikes to Los Angeles, and (2) talent. Given that he spends the song’s opening moments shouting out Ye for “giving me all this clout on Instagram and everybody on his page is clicking on me ‘cause of him,” it probably wouldn’t be wrong to add passion to the list, too. ProdbyZaqq is very obviously not serious about pursuing a long-term musical career. Ever the brainchild of who gave him his platform in the first place, he is far more interested in discovering the limits of social media, and toying with how far he can push them.

What’s somewhat more intriguing is the notion that ProdbyZaqq did not, by any means, need to release a song in order to cement his newfound fame. Long before he graced YouTube with yet one more amateur rap video, his comment section activity alone was enough to make him a steadily familiar name on the hip-hop internet. From Ye’s official Reddit forum, to the aforementioned Twitter complaints, and even to the memes populating ironic rap pages, he had grown into a comical antagonist, one of several side-characters to Ye’s long-unfurling cult-of-personality. It’s scary to imagine what he could have accomplished had the song actually been good.

Say his newfangled fame inspired him to lock down on his musical merits once and for all, that perhaps he got in touch with someone like Pi’erre Bourne or Zaytoven—both of whom would at least know his name—and curated a megahit. He had already duct-taped America’s ear to his machinations by way of aggravating Instagram maneuvers, and whether they liked it or not, America was now primed to hear whatever he had to say sonically. Where could he be right now if he hadn’t taken it as another joke? One track was likely the difference-maker between being featured on Donda 2 and commenting about it online. Spoiler alert: Prodbyzaqq is still commenting about Donda 2 online.

Figures like our least favorite Ye cheerleader illustrate not only the internet’s widened window of opportunity but also its crippling low end.

“Chief Keef, Bobby Shmurda, Desiigner, Lil B, Fetty Wap and many more all used free music services, video platforms and the internet in general to transition from independent to label-represented,” Stephanie Smith-Strickland wrote in a Highsnobiety analysis of Soulja Boy’s influence. “Even the songs that first brought them attention follow the Soulja Boy method—they feature simple lyrics, catchy beats, and more than a few even have dedicated dances. These days everyone wants to be internet famous so the competition is certainly a lot stiffer, but with a little patience and a touch of luck, the blueprint still works.”

A common grievance among the generation that walked their mixtapes to Los Angeles is that the internet has taken a great deal of quality away from music. It’s a business, the aforementioned Thanksgiving rapper’s 40-year-old uncle would likely warn him, and everything is structured “nowadays” to value abundance of content over abundance of meaning. A look at ProdbyZaqq’s career arc makes this painfully undeniable even for people that would argue against social media doomsdayers; his Instagram page is packed with highlight reel material of video shoots, posed photo ops and significant screenshots from the days of Ye following him. For all of this bragging, the music certainly doesn’t live up to the hype. He is very much taking up cultural space that could be occupied by someone else.

But the catch with the internet, and what makes ProdbyZaqq impossible to be mad at, is that anyone can occupy that void. There is no application, skill requirement, nor suited manager sighing on his way to fetch the crumpled notes underneath his door. All there is is space, and a few billions of eyes that have no choice but to watch who occupies it. It could be me; it could be you; it could be a mediocre producer from New Jersey who shamelessly chases clout online.

Some two decades ago, there was no social media, and it was an upstart, peasy-haired geek no older than 20. His name was Kanye West, and he was an uninvited guest in the offices of Roc-A-Fella Records, playing his own music for people that could not have cared less.

Although ProdbyZaqq is no Ye—or, at least not yet—it wouldn’t be too far to say that, as annoying as it is, he’s following in legendary footsteps. In the 21st century, a day where the command of social media far outweighs that of the record industry, we ourselves are the bored record execs. Our unsolicited office visits are the numerous upstart rappers that flood comment sections. The internet is the industry. And it’s anyone’s game.

Matt • Mar 1, 2022 at 10:29 am CST

Although Kanye was going door-to-door playing All Falls Down and stuff from TCD to gain attention, he was definitely not “uninvited” at Roc-a-Fella.

Justin • Feb 26, 2022 at 3:05 am CST

This article is really interesting and well done. Enjoyed reading!