Remember that new Spider-Man movie?

Of course you do. How could anyone forget the cinematic phenomenon that single-handedly reasserted the viability of movie theaters in the wake of a global pandemic by smashing box office records and incorporating three different iterations of the same iconic character across three different decades in an Endgame-esque spectacle?

Well, after multiple subsequent viewings and shedding the rose-tinted lenses of recency bias, I have come to realize that it’s just not that good.

This isn’t to say that it’s a bad movie. Aunt May’s tragic demise and the surprisingly visceral final confrontation between Tom Holland’s heartbroken Peter Parker and Willem Defoe’s brilliant Green Goblin both enabled Holland to add some much-needed shades of angst to a character whose whimsical demeanor belies the many hardships he has endured as one of the most tragic figures in Marvel Comics.

However, these aspects are overshadowed by the film’s lazy writing, which sacrifices storytelling in favor of appealing to the audiences’ sentimental side, allowing the film to ride the nostalgia wave into a massive profit. While it was satisfying (and even downright cathartic) to finally get closure for the stories of the Spider-Men of my childhood, it was at the expense of characters in the main Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), the universe in which the film takes place.

A prominent example of this is the film’s straight-up character assassination of Benedict Cumberbatch’s character, the sorcerer supreme Dr. Strange. Characters from past non-MCU Spider-Man cross-over into “No Way Home” through his supremely stupid decision to rip a tear in the fabric of the multiverse to help Peter Parker and his friends confront their most formidable foe yet—MIT admissions officers (I’m not kidding). Dr. Strange then recklessly orders the teenaged trio to clean up after his mess by rounding up highly dangerous villains from alternate universes, something he eloquently describes as “Scooby-doo[ing] this shit!” This is not the same Dr. Strange who shouldered the responsibility of protecting an infinity stone and played an instrumental role in taking down Mad Titan Thanos.

I would be lying if I said I wasn’t among the droves of fans who flooded theaters and cheered at the top of their lungs upon seeing Andrew Garfield and Tobey Maguire step back into their beloved roles, and I really can’t criticize a film that provided such an enjoyable experience too harshly. However, what really troubles me are the possible implications for the broader film industry that the success of a film so reliant on preexisting films may have.

Interconnected cinematic universes have been all the rage in Hollywood for quite some time, with numerous franchises following the template that was laid by the MCU, including its main comic book rival DC, the “Star Wars” franchise and, more recently, “Lord of the Rings.” However, such an emphasis on world-building across franchises has diluted the quality of storytelling and character development by pinning these responsibilities on future films to create some grand overarching story arc and maximize revenue. At their best, films in cinematic universes have become drawn-out episodes of shows scaled up for the big screen, and at their worst, these films have been reduced to glorified trailers for future installments.

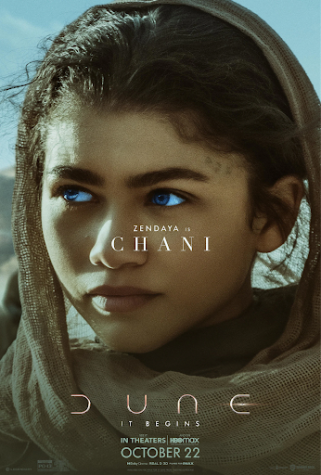

Along with Spider-Man: No Way Home, “Dune” was one of the most critically and commercially successful films of 2021, earning 10 nominations at this year’s Academy Awards and grossing over $300 million worldwide. While it did an excellent job of capturing the size and scope of the sweeping sandscapes and sandworms from Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel of the same name, the film also fell into the trap of swapping story for spectacle and setting up sequels. Similar to the notorious Hobbit trilogy, this film warps the pacing of its source material by stretching the content of a single novel into multiple movies. Moreover, even the way the film was advertised misled viewers into purchasing tickets to see a character whose only real purpose was to tease events of the sequel. Zendaya’s character, Chani, was the most heavily marketed character of the entire film—after its protagonist Timothée Chalamet’s Paul Atreides—but she had such little screen time that she could be completely missed during a poorly-timed bathroom break, appearing for a mere seven minutes of the film’s two-and-a-half-hour runtime.

The latest Spider-Man film is able to bypass these issues because it relies exclusively on the interplay between beloved characters introduced and established in past films. However, the exclusive use of already developed characters raises yet another issue in terms of the cinematic universe as a whole. While there was a sizable chunk of audience members who thoroughly appreciated the film, those who were not completely immersed in the MCU left the theater completely baffled.

Why is having the power of the sun in the palm of his hand such a big deal for the tentacle guy?

Why did Garfield’s Spider-Man cry after saving Holland Spider-Man’s girl from a fall?

What is Maguire and Garfield Spider-Man’s deal with evil best friends?

Without having watched all seven previous Spider-Man films, it is impossible to fully grasp many references and even certain plot points of “No Way Home,” alienating a large subset of moviegoers as a result. The issue of making previous films pre-requisites is slowly starting to snowball as more and more films are being produced within cinematic universes; if this trend becomes the focal point of Hollywood movies, it could drive people away from the cinematic medium as a whole.

To bypass the pitfalls of the elaborate over-complex web of interconnected films, it is important to consider the aspects that make films unique and impactful in the first place. Unlike television shows, which can afford to tell drawn-out and meandering stories across episodes, films should focus on compacting and delivering poignant stories and ideas within their given runtime. Many of the most impactful films can be enjoyed in a vacuum and do not require hours of context for viewers to fully appreciate what they are trying to convey.

Now, I’m not calling for the end of film franchises, but rather an overhaul on the approach and execution of films within them. Say what you want about DC films and their failure to launch a cinematic universe of their own, but the kinds of things they were able to do with the Batman property is a solid example of proper storytelling and filmmaking within the scope of a single franchise. In the past couple of years, DC has been able to churn out many unique interpretations pertaining to the Batman mythos, ranging from a thematically rich three-part crime saga, which tells three distinct tales of fear, corruption and the duality between heroism and villainy, to a deeply provoking and disturbing character study of one of his greatest adversaries. The folks at Marvel Studios, by contrast, were more concerned with laying the framework for one of the most drawn-out cinematic cash cows franchises in the history of Hollywood.

There is no better way to illustrate the dissonance between the two styles of filmmaking than comparing the two studios’ upcoming releases.

The upcoming Batman film is not going to be some kind of contrived team-up between Ben Affleck’s grizzled and aging Batman, George Clooney’s campier credit-card-carrying Batman and Will Arnett’s Lego Batman. Instead, it stars Robert Pattinson as a younger and more inexperienced iteration of the character from a fresh angle, influenced by street-level noir-style films like “Taxi Driver” and “The French Connection.”

The next major Marvel movie shines the spotlight on the supremely scatterbrained Dr Strange in the third multiverse-centric Marvel film of the past five years, which is rumored to feature appearances of characters as outlandish as an Iron Man played by Tom Cruise and Patrick Stewart’s Professor X. At this point, I wouldn’t even be surprised if Marvel Studios decided to buy the rights from Warner Bros. to have Scooby-Doo face off against Dr. Strange in a climactic final confrontation to avenge his reputation after the slanderous remark made against him in “No Way Home.”

Things are clearly getting out of hand.

Instead of having studios launch a full-out arms race to create a series of films with the most outrageous and convoluted crossovers and drawn-out story arcs, it’s high time that Hollywood filmmakers begin making movies for the sake of making movies.