More than a year ago, my peers Miguel Moravec and Emily Irigoyen kicked off the fossil fuel divestment campaign at Vanderbilt University. Since then, the campaign has made significant headway. Many students, including myself, have joined the movement as activists. Both Vanderbilt Student Government and the Graduate Student Council have passed divestment resolutions. Over 1,500 individuals have signed the divestment petition, and multiple large protests have been organized. The movement has even gained the attention of former vice president Al Gore, who recently endorsed divestment at Vanderbilt.

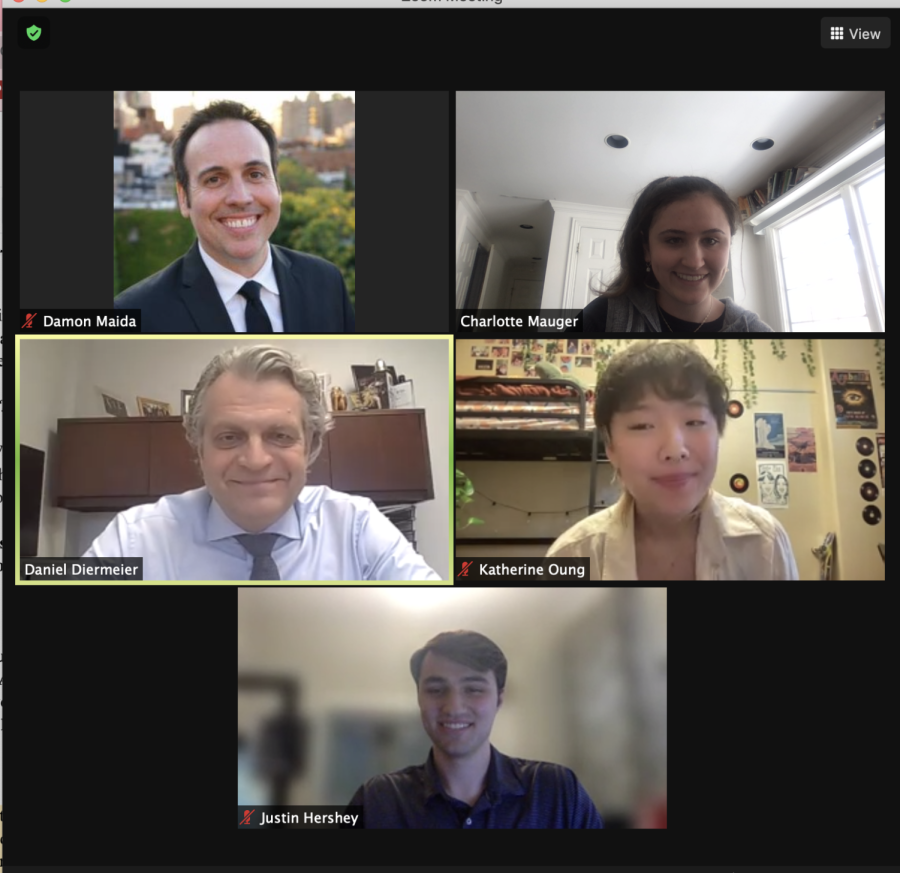

As the campaign has progressed, students, faculty and alumni have all pressured Chancellor Daniel Diermeier on the issue. In response, Diermeier has clearly stated that he does not support Vanderbilt divesting its endowment from fossil fuel investments, which are estimated to be around $500 million. However, the Chancellor’s core arguments are severely flawed. As students who seek meaningful debate on this matter, it’s time we hold him intellectually accountable for his weak arguments. To quote the Chancellor himself from his Founder’s Walk address, we ask him to “always be open to being convinced by the other side, open to learning something new, open to gaining a broader perspective.”

I don’t want to mischaracterize the Chancellor’s position, so I strongly suggest that everyone read his full responses in his Nov. 19, 2020, Apr. 25, 2021, and Dec. 8. 2021, debriefs with The Vanderbilt Hustler. Nonetheless, Chancellor Diermeier’s arguments against fossil fuel divestment are summarized as the following:

As a university, Vanderbilt students and faculty should debate the issue of fossil fuel divestment (versus shareholder activism). However, the university itself should not “prescribe what a particular policy solution should be.”

By divesting, Vanderbilt would be establishing a “party line” and taking the stance that divestment is the “best way to address climate change.” Universities “should not take advocacy positions on public policy issues.” In addition, the purpose of the endowment is to maximize returns, not to be an “advocacy tool.”

Diermeier fundamentally mischaracterizes our campaign’s argument for fossil fuel divestment. Had the Chancellor taken the time to actually meet with students and hear our pitch, perhaps he would know our position. Nevertheless, the campaign’s motivations are not to use divestment as “the best policy solution to address climate change.”

Rather, we argue that divestment is in Vanderbilt’s own interests, as fossil fuel investments actively hurt our reputation, community and endowment.

The reputational risks of remaining invested in fossil fuels are clear. Vanderbilt is already ranked in the bottom 25th percentile for sustainability among the top 40 schools, partly due to its fossil fuel investments. For context, most of Vanderbilt’s direct competitors have publicly committed to divesting from fossil fuels, including Dartmouth, Brown, Cornell, Columbia, Georgetown and even Harvard University. Considering that 78 percent of applicants weigh their university’s environmental stances in making their college decisions, continued inaction on this mainstream issue may hurt Vanderbilt’s ability to attract top students and faculty.

In terms of our community, as we saw with Waverly, Tennessee, last summer, extreme weather events continue to threaten the lives of both faculty and students as well as cause more than 8 million premature deaths per year globally. The question is simple: Why is Vanderbilt continuing to fund an industry that hurts both its own community and the world’s most vulnerable populations?

This leads us to the financial case for divestment.

The fact of the matter is that divestment is good for the endowment. Multiple studies, including research done by the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock, have found that divested portfolios either match or outperform non-divesting portfolios. In addition, as Gore pointed out, fossil fuels have been among the worst-performing sectors in the past decade and currently face existential risks as an industry. For the Chancellor and anyone interested, please read a white paper that I personally wrote, entitled “Divestment 101: The Case for Fossil Fuel Divestment at Vanderbilt University,” to go deeper on this part of our argument. This report also explores the fact that because the university invests in fossil fuel companies through externally managed funds, Vanderbilt does not directly engage in meaningful shareholder activism.

Finally, we ask the Chancellor: if divesting from fossil fuels is taking a policy “party line,” what does that make for the fact that we are actively investing in fossil fuels? Is that not a policy choice in itself? Or do status-quo decisions not count?

We’ll let him answer that. But the reality is that several times throughout history, Vanderbilt has chosen to challenge the status quo.

When top universities lacked racial and ethnic representation, Vanderbilt made the choice to seek a diverse student body and has become a leader in recruiting talented students of color. When the country faced economic hardship in 2008 and other universities reduced their commitment to financial aid, Vanderbilt made the choice to establish several policies which eventually became the celebrated Opportunity Vanderbilt financial aid program.

If Diermeier was around when these changes were proposed, would he state that the role of Vanderbilt is to only “discuss and debate” racial and economic issues but not act on them? Would he have stonewalled these policies, like he is doing with divestment, and argue that Vanderbilt should “not take advocacy positions on public policy issues?”

We hope not.

The bottom line is that throughout these decisions, Vanderbilt recognized that changing its previous policies was in its best interests. In doing so, the university has transformed into the amazing institution that it is today, the institution that so many of us are proud to be a part of.

Chancellor Diermeier, let’s act in Vanderbilt’s best interests and make the choice to divest from fossil fuels.

Class of 2024 • Jan 12, 2022 at 12:02 pm CST

i liked the line calling out the Chancellor’s bs about “not taking a party line” like what ever was that ?

Class of 84 • Jan 12, 2022 at 11:38 am CST

Yes … fossil fuel divestment is mainstream for the Ivies now. The university should create a divestment task force, at the very least, to explore the financial benefits of this …

Hutch • Jan 12, 2022 at 11:22 am CST

It is far from established that ESG investment criteria deliver superior financial returns. When subjectively defined “values” are removed from consideration as an asset value it gets down to who is the best selector of investments. There is plenty of commentary regarding the relative worth of ESG in financial investing.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonmoore/2021/04/07/researchers-find-that-esg-investing-may-benefit-consultants-more-than-investors/?sh=5326f5c7565f

An accepted definition is “an educational institution designed for instruction, examination, or both, of students in many branches of advanced learning, conferring degrees in various faculties, and often embodying colleges and similar institutions.”

Advocates who attempt to co-opt a true university into an advocacy platform for particular social causes contradicts the raison d’etre for an institution being considered a university.

Josh • Jan 12, 2022 at 4:54 pm CST

Hi Hutch, this is Josh (author of the editorial). Thanks for the comment.

Yes, there is mixed evidence of ESG performance due to the selection factor, but that’s but a small part of our campaign’s asks. Fossil fuel divestment is what we’re advocating for, and it’s important to note that ESG

integration != divestment. Here are some reasons why we are not advocating for solely ESG integration. (1) Some funds that brand themselves as ESG even include investments in fossil fuel companies (https://fossilfreefunds.org/funds?q=esg). (2) Bloomberg recently did an excellent analysis of the flaws of the MSCI ESG methodology (the largest ESG rating company)

(https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-what-is-esg investing-msci-ratings-focus-on-corporate-bottom-line/).

Again, what we’re advocating for is outright divestment from the fossil fuel sector.

And the facts show the divestment (not ESG integration) leads to equal or better financial performance. In my editorial, I cite several sources that support this claim: the comprehensive studies by BlackRock and

Maketa, publicly available data on the stock prices of fossil fuel companies.

Even if we pretended that fossil fuel divestment had zero benefits for Vanderbilt’s reputation or the planet, it would still be worth doing solely for the financial reasons. It admittedly is awfully convenient, however, when your financial interests align with the social good.

Hutch • Jan 12, 2022 at 9:38 pm CST

Hi Josh, I understand your advocacy but am very reluctant to accept your statement “And the facts show the divestment (not ESG integration) leads to equal or better financial performance.” Again, the financial jury remains out on the validity of that statement.

Yes, in some instances ESG funds have outperformed an excellent example being the EU funds. However, the EU also regulates their energy industry with a strong bias towards climate change considerations distorting the energy industry’s performance in the market place.

The BlackRock study is only one of many. Larry Fink Blackrock CEO is a well known advocate of ESG funds. He is an outstanding investor who has now flavored his company as a social advocate. He has made a lot of money for himself and others, but his ESG success is very short term in the market.

By inserting governmental regulatory and political bias into the marketplace through regulatory restrictions on energy companies above market returns for ESG funds can easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I suggest that advocative regulation distorts the market place introducing economic inefficiency the costs of which are born mainly by the economic middle and lower class in the form of inflation today’s gas prices being an example. It is undeniable that market inefficiency begets dollar costs.

Rather than distorting the marketplace by regulatory and executive fiat let the Federal legislative branch decide as they reflect the will of the voters, with one caveat. That being complete and unbiased information be made freely and omnipotently available to the public.

The current endemic media’s advocative bias’s are probably the greatest impediment to reasonable change unfortunately as emotion appears to trump logic as the fourth estate’s modus operandi.

Your perspective is one of great sympathy to the public at large. However, there are substantive short term increased costs involved that negatively affect the the standard of living of those in the most precarious position to bear those costs. They are experiencing those costs today and are unhappy particularly at the gas pump..

The high density energy sector enabled the US to become the economic success it is today. This pillar of strength should be addressed with the respect it deserves because of its success. Of course it has had unintended consequences as do many other economic endeavors.

It will be a huge mistake to treat the high density energy like some statue statute to be toppled in the night while the perpetrators celebrate only to drive home in their energy intensive vehicles.

Hutch • Jan 17, 2022 at 10:35 am CST

Since the “BlackRock studies” are cited in you response please have a look at what BlackRock is and has been doing to pricing first time home buyers out of the market. https://marinpost.org/blog/2022/1/8/the-tina-trade.

The BlackRock ESG program appears to be providing a publicity veil for BlackRock’s Wolf of Wall Street behavior in our nation’s housing market especially for first time home buyers.

Chuck Kaiser • Feb 21, 2022 at 6:25 pm CST

Article by the CEO of a leading private equity firm on the forefront of ESG investing.

https://fortune.com/2022/02/10/we-cant-invest-in-the-energy-transition-if-we-stop-investing-in-energy-climate-net-zero-kewsong-lee/

Kendall • Jan 11, 2022 at 1:22 pm CST

Wonderful write-up, Josh. The financial argument for divestment is clear. You are clearly well-learned on a topic that is oftentimes hard to grasp, kudos to you!

Tim Cutler '77 • Jan 10, 2022 at 10:05 am CST

Leave the decisions about capital to the professional capitalists.

John Doe • Jan 10, 2022 at 10:41 pm CST

Hey Mr Cutler, thanks for your input! But uh, Mr. Doh is known as easily one of the brightest minds at one of the best schools in the world. Not only has he repeatedly worked in, you guessed it – capital management and investment portfolios – but he is also headed off to work at McKenzie, the #1 firm in the world with less than a 1% acceptance rate. I’d take his word for it ?

Hutch • Jan 12, 2022 at 10:32 am CST

Mr Doh is just beginning his commercial work career. He understandably lacks experience in that sector. As an advocate he may be well qualified. The correct name is McKinsey & Company and no it is not generally recognized as the “#1 firm in the world”. It has had myriad ethical accusations during the past decade.

Class of 2024 • Jan 12, 2022 at 11:48 am CST

engaging with the substance of the well cited arguments ? ? ?

Posting a one-liner about how capitalists are the best at capitalism ?️ ?️ ?️