CORRECTION: This article has been clarified to state that the Phase 1 trial was administered by university partners in Atlanta, GA and Seattle, WA and not by VUMC.

After Dolly Parton’s $1 million dollar donation to VUMC this past April as well as Moderna and Pfizer’s November appeals to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use authorization review, The Hustler asks: how has Vanderbilt shaped the COVID-19 vaccine response?

National news outlets have reported on the contributions of Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and Dr. Mark Denison’s lab towards COVID-19 vaccine development. VUMC oversaw Phase 1 and 3 trials of Moderna’s vaccine candidate and is currently administering a Phase 3 trial of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine candidate.

Coronaviruses and Vanderbilt’s Denison Lab

Although the novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus emerged in China in late 2019, Vanderbilt’s coronavirus research dates back over 30 years. Dr. Mark Denison, VUMC professor of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, first published his studies of coronaviruses in 1987. COVID-19 is just one of the many viruses within the coronavirus family, and prior to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the Denison Lab at VUMC researched the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV coronaviruses.

Leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Denison Lab mainly studied the MERS-CoV virus and its ongoing outbreak in the Middle East. Dr. Andrea Pruijssers, a Research Assistant Professor at VUMC and a faculty member of the Denison Lab, noted that the lack of antiviral treatments for MERS-CoV and other coronaviruses predicted the lethality of a coronavirus outbreak.

“There were no antivirals against that virus or any, so we knew that if there was ever going to be a pandemic, then we would be in trouble because we have nothing to treat with,” Pruijssers said.

The Denison Lab’s foundation of coronavirus knowledge and experience experimenting with coronaviruses positioned the lab to pivot towards responding to SARS-CoV-2 in January, as the virus began to transcend national borders.

“Once it was clear that the virus was not going to be contained within China, that’s when we started going into high gear and preparing to study this virus in detail,” Pruijssers said.

Emergence of the COVID-19 Challenge

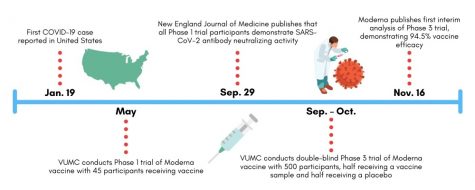

The globalization of COVID-19 and the identification of the United States’ first COVID-19 case in Jan. 2020 concentrated national research efforts around COVID-19 response. As the reality of the pandemic crystallized, foundations, drug companies and the federal government approached the Denison Lab for support.

As there were originally no FDA-approved treatments for SARS-CoV-2 infection, Pruijssers explained that the Denison Lab began its COVID-19 response efforts by testing a series of experimental antiviral compounds designed to slow the replication of SARS-CoV-2. Despite evidence suggesting various drugs’ efficacy in SARS-CoV-2 inhibition, a proofreading enzyme unique to the SARS-CoV-2 virus has equipped it with continued resistance to many of the antiviral drugs tested by the Denison Lab. Pruijssers attested that even Remdesivir underperformed in patients when compared to its inhibitory activity in the lab.

“We have tested lots and lots of drugs, and none of them work,” Pruijssers said. “It’s really challenging in that respect.”

A Step Towards a Vaccine: Phase 1 Moderna Vaccine Trials

The Denison Lab conducted laboratory testing of the immune response to Moderna’s vaccine as part of a Phase 1 trial administered in Atlanta and Seattle in May. This round of Phase 1 testing consisted of a cohort of 45 volunteers who all received a dosage of Moderna’s experimental vaccine. The study did not include a placebo group. According to the FDA drug review process, Phase 1 testing follows preclinical animal testing and the approval of an investigational new drug application submitted to the FDA.

The aims of this Phase 1 trial included evaluating the safety of the vaccine, assessing the appropriate dosage and understanding the volunteers’ immune response to vaccination. Given the Denison Lab’s decades of experience researching coronaviruses, the team took the lead in studying blood samples of these 45 participants to measure their immunological responses to the vaccine.

The Denison Lab used these blood samples to test the Moderna vaccine’s efficacy in evoking a strong memory immune response to reinfection by SARS-CoV-2. The lab carried out these tests by extracting a small sample of blood from participants, mixing this blood with live SARS-CoV-2 viruses in the lab and evaluating the level (titer) of neutralizing antibodies in the blood.

“We showed that participants had very high neutralizing titers, which is good news because neutralizing antibodies are often a correlate of protection,” Pruijssers said.

The Denison Lab recently co-authored a publication in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating that these Phase 1 participants continued to generate antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 119 days after vaccination. According to the paper, this is a promising sign that the Moderna vaccine may equip recipients with long-term immunity to COVID-19.

Phase 3 Moderna Vaccine Trials

This fall, Vanderbilt contributed to the nationwide Phase 3 trial of Moderna’s vaccine candidate. The trial made headlines in November as it demonstrated the vaccine’s 94.5 percent efficacy rate and served as the final step before FDA emergency use authorization review. Nationally, the Phase 3 trial consisted of over 30,000 adults aged 18+ from a diverse range of backgrounds, including 7,000 volunteers aged 65+ and 5,000 volunteers with chronic illnesses putting them at-risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms.

In July, VUMC began recruiting 500 participants to contribute to the trial. These participants received the initial and booster injections of Moderna’s vaccine at VUMC between September and October. Since receiving the vaccination, VUMC researchers have monitored their immune response and symptoms in a similar manner to that conducted for the Phase 1 trial. Unlike Phase 1 testing, researchers conducted the Phase 3 trial in a double-blind manner where neither participant nor administrator knows which individuals received a vaccine rather than a placebo. Instead, the researchers assess immune response independent of vaccine versus placebo status and then trace their results to the respective groups afterward.

Phase 3 trial researchers observed 95 cases of COVID-19 among participants in November, 90 of which were traced to the placebo group and five to the vaccine group, meaning that the Moderna vaccine demonstrated 94.5 percent efficacy in preventing COVID-19.

“Vanderbilt’s played a role in showing that there is a good immune response to the vaccine, and then we played a role in proving that it works in the real world,” Director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program Dr. Buddy Creech said.

A Vanderbilt Chemistry Professor’s Trial Experience

Dr. Steven Townsend, an Assistant Professor of Chemistry in the College of Arts & Science, volunteered for the Phase 3 trial and received his initial shot of Moderna’s experimental vaccine at VUMC in September. Townsend volunteered for the trial to serve as an example of the safety of a vaccine for his students and to mitigate mistrust in the medical community expressed by some of his Black peers and the American community at-large.

“When I talk to people in my family, I know that there is a lot of mistrust in the institution of medicine due to a lot of atrocities that happened,” Townsend said. “Those things don’t go away. I think the way you remedy that is representation.”

Due to the double-blind nature of the Phase 3 trial, Townsend was not aware of whether he received the vaccine or a placebo. However, Townsend did recall that he felt a fever and exhaustion in the days after receiving his second injection. These results would have been consistent with a heightened immune response to reinfection by SARS-CoV-2, which prompted Townsend to speculate that he received the vaccine instead of a placebo.

“For me, the result was a low-grade fever. I was exhausted for 24 hours, and I had the chills,” Townsend said. “It was weird. The next morning, it was like nothing had happened, and I ran three miles.”

Following his initial September injection, VUMC researchers have sampled Townsend’s blood three times. Trial administrators have also periodically tested him for COVID-19 positivity and interviewed him about COVID-19 exposure. Townsend and other Phase 3 trial participants will remain in the study for two years to allow researchers to assess the short and long-term effects of the vaccine.

Townsend hopes that his actions will encourage student adoption of the COVID-19 vaccine and promote Vanderbilt’s safe return to pre-pandemic campus life.

“I’m hopeful that most students will trust me and others that this is a safe vaccine and that if it wasn’t perfect, it wouldn’t roll out,” Townsend said. “I’m in this trial, and I’m here talking to you now.”

Vaccine Legacy

Creech envisions that the COVID-19 vaccine efforts will have a lasting impact on the future of vaccine technology and public-private partnerships. In contrast to traditional vaccine technology, Moderna’s vaccine is composed of messenger RNA, or a segment of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material, instead of a weakened virus or viral protein. This structural difference makes the vaccine quicker to design and manufacture than a full viral vaccine.

Additionally, the collaboration across the National Institutes of Health (NIH), research institutions like Vanderbilt and drug companies like Moderna facilitated by Operation Warp Speed has demonstrated the power of collective action in driving scientific breakthroughs.

VUMC is currently engaging in Phase 3 trials of a Johnson & Johnson vaccine candidate. As the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines continue, Creech is optimistic that the maintenance of strong public-private partnerships will contribute to more breakthroughs.

“When we are unified in our goal and fully resourced financially, we can do remarkable things very quickly,” Creech said.