Content warning: this article discusses the prevalence of suicide and suicidal behaviors among college students and on Vanderbilt’s campus.

Around 1,000 backpacks were spread out across Library Lawn Oct. 22, accompanied by written stories, posters and volunteers waiting to engage with students who stumbled onto the large display. The exhibit was part of the traveling “Send Silence Packing” campaign, an effort of the national Active Minds organization, to “end the silence” around suicide and connect students to resources for support and action.

“We felt as though, in order to start more of a campus wide conversation about mental health, we needed to do something that was more public, so that way people who didn’t already have this niche interest in mental health could get connected with the topic and engage in the discourse,” Vanderbilt Active Minds co-president Sara Conley said.

Since the Vanderbilt Active Minds chapter started six years ago, hosting the Send Silence Packing exhibit has been an organizational goal. After fundraising for years and dedicating much of their AcFee funding, the Vanderbilt chapter came up with the $5,000 needed to bring the display and the national Active Minds representatives to campus.

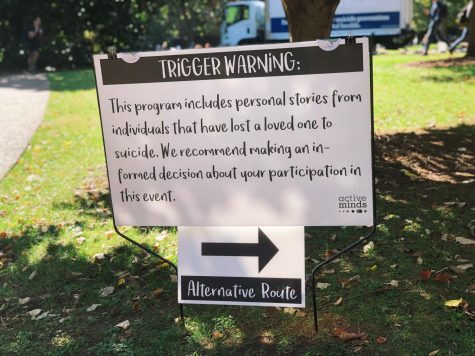

Due to the potentially triggering nature of the exhibit, which includes stories of students who have died by suicide, Active Minds put up flyers in preparation for the event, placed trigger warnings around the perimeter of Library Lawn and mapped out an alternate route for students who did not want to engage with the display. The Vanderbilt organizers also had members of the University Counseling Center (UCC) and Center for Student Wellbeing (CSW) at the display, and stationed volunteers at the exhibit to help connect any emotionally affected students to resources.

“We had at one point a prayer circle, we had people crying, we had people coming up and asking how they could get more involved with Active Minds,” Conley said. “The faculty engagement was actually really excellent, we had teachers walking to class and they stopped by and really sat with it for a while and came up to talk to us and express approval.”

Conley said that another motivation of the group was to proactively talk about suicidality at Vanderbilt. Too often, she said, Vanderbilt addresses suicide specifically only after someone has died.

Data regarding death by suicide is not available at Vanderbilt, but representatives from the Student Care Network said they believe the numbers to be low. Todd Weinman, director of the UCC, said this due to the difficult nature of determining whether a death is accidental and the stigma around suicide, which may cause underreporting of suicide.

The majority of large public colleges don’t track suicides, the Associated Press found, many for the same reasons that Vanderbilt’s representatives mentioned.

“Like on many campuses, it has been quite challenging to systematically and accurately collect data around specific deaths by suicide due to the relatively small number of overall deaths and the family privacy issues that can be involved, and thus that has not been something we have regularly included in the data we share in our end of year reports,” Weinman said.

Earlier this summer, a new law took effect in Tennessee requiring public colleges and universities to create suicide prevention plans for students, faculty and staff and then publicize that plan at least once per semester.

As a private university, Vanderbilt is not subject to the new Tennessee law, but Weinman said that Vanderbilt is already going above what the new law requires, with multiple avenues of suicide prevention training and regular programming to introduce students to the mental health resources on campus.

“I think what is happening at Vanderbilt far exceeds the requirements and spirit of the new state law and is actually a model for other schools around mental health and suicide prevention,” Weinman said.

Recent data from the 2019 national Healthy Minds survey of more than 40,000 respondents found that 15.1 percent of undergraduates reported suicidal ideation in the last year, 6.8 percent of undergraduates reportedly made a suicide plan and 1.7 percent attempted suicide. The 2019 statistics represent a year-over-year increase in percentage of students reporting the aforementioned behaviors.

Vanderbilt’s most recent mental health data was collected in the fall of 2016 using the Healthy Minds Survey. The results of that survey found that 10.1 percent of Vanderbilt undergraduates reported suicidal ideation, 3.3 percent reported having made a suicide plan and .6 percent reported having attempted suicide. All of the university’s statistics are below the national averages from that year.

“We actually know that we’re very good at helping students when they’re in crisis, whether it be through the crisis care hours at the counseling center or the hospital emergency room,” Weinman said. “But what we want to do is, as much as possible not get to that point with students. For me, that’s about doing it in a caring way that’s encouraging students’ natural desire to be successful and to get help.”

In recent years, Vanderbilt has greatly expanded its mental health care network, which Office of Student Care Coordination (OSCC) Director Lisa Clapper says is due to ever-increasing demand for mental health services on campus. Today, the Student Care Network includes and directs students towards resources for mental, emotional, physical, financial, spiritual, social and other needs. In the year since the OSCC opened, the office has already moved locations to accommodate a growing staff needed to meet student engagement.

The university offers two primary means of training to prepare students and staff recognize and respond to mental health crises, namely the Mental Health Awareness & Prevention of Suicide (MAPS) in-person training and an online module called Kognito At-Risk. Both of these trainings are available to students, faculty and staff who are interested in learning more about crisis prevention.

Rachel Eskridge, director of the Center for Student Wellbeing, said that her office has seen increased interest from faculty and various schools, including Peabody and Nursing, in accessing these trainings. Others, like CASPAR pre-major advisors, are required to take the Kognito training and both faculty and student VUceptors go through MAPS. Last summer, she said, her office worked with the Vanderbilt Police Department to help increase their comfort with responding to students in crisis.

“Because so many faculty and staff go through the Kognito training and go through the MAPS training, they generally know the steps to take, so when there is a crisis, that response becomes very immediate and they’re brought to the right places at the right time, which is the most helpful thing you can do,” Eskridge said.

One of the key highlights of the Vanderbilt Healthy Minds Survey noted was that 70 percent of survey respondents reported seeking counseling or support from someone who was not a healthcare professional. With that in mind, mental health professionals on campus are looking to ensure that the culture at Vanderbilt is one in which everyone knows where to turn to support a friend in need.

“We’re not planning to train every student to be a therapist or a counselor or that they need to know all the steps – we’re basically just trying to get a caring community where, when you notice something that’s kind of off or you’re concerned about someone or something a little scary or unusual, that you talk to someone,” Weinman said. “Because it may be there’s five other people that are also noticing that same thing and all of the sudden, we can put that information together. I’m amazed once people step up; it’s such a helpful thing.”

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor.