*names have been changed

When Bryan Stromer ‘17 published an op-ed in The Washington Post calling out the inattention Vanderbilt paid to students with disabilities during his time at the university, he was nervous about how the university he loved would respond. His piece, which lauded the courses he took that allowed him to study disability culture, detailed the ways in which Vanderbilt’s understanding of disability was not only lacking, but perpetuated a sense of shame around having a disability.

“I had the chance to work with a lot of administrators in advocacy and I really admired them and I didn’t want this to necessarily dampen that, but I think one of the hard things about when you go for a really public platform, there’s sometimes a wall that’s built up around that,” Stromer said.

Still, he felt it necessary to risk his relationship with administration for the sake of pushing for change. In addition to his op-ed, Stromer posted a call to action on Facebook and sponsored a Change.org petition, both asking the university to recognize disability as an aspect of diversity, rather than a legal obligation that the university needed to meet.

“I think the mindset didn’t reflect this new way of thinking of disability. I remember, one of the things I talked about is at RA training, we wouldn’t have any discussions really around disability, but we would have discussions around race, we would have discussions around religion and sexual orientation and gender and all the other kinds of protected classes,” Stromer said. “That was something that I remember even when I would go to events on campus, disability was never included. Disability wasn’t part of that narrative around diversity and inclusion for a long, long time.

After the piece was published, a Vanderbilt spokesperson issued a response, included at the bottom of the Washington Post piece, referencing the university’s dedication to disabilities research and services offered on campus. The response also mentioned the work Vanderbilt was doing at the time to assess the accessibility of campus for students with disabilities. That assessment took place during the summer after Stromer graduated, and led to the creation of the Advisory Accessibility Task Force. While that assessment focused on the physical aspects of disability, an effort out of the office of Melissa Thomas-Hunt, Vice Provost for Inclusive Excellence, called InclusAbility launched earlier this year, aimed at including disability in discussions of diversity on campus.

“I’m so excited about [these initiatives] because there were not events like this when I was a student, and this is something that I was really looking for, so to see an administrator like Melissa Thomas-Hunt take this on and really bring it to life has been so exciting for me,” Stromer said. “I think it represents a huge change in how Vanderbilt views disability.”

Despite these efforts, students with disabilities have said that Vanderbilt in many ways still has a long way to go toward fully embracing its disabled communities. In particular, students mentioned the feeling that Vanderbilt operates under a compliance based mindset, filling just what students are legally entitled to, rather than attempting to go beyond and make students with disabilities feel like a valued identity on campus. Even with this compliance focus, though, students said the university sometimes still fails to meet students’ basic needs.

“In my experience here at Vanderbilt, I have not really seen them go past the letter of the law,” Max*, a student who receives accommodations, said. “At the end of the day here at Vanderbilt, if I see them reaching the letter of the law accommodations wise, sometimes I feel like that’s a win for the student body. That’s how bad it often is here. I think a lot of people at Student Access Services are doing their best, but there are certain things they can do better.”

An Expectation of Self-Advocacy

In higher education, the burden is on students to seek out the services they need. When Grace* first toured Vanderbilt after receiving her acceptance, she made a point to visit the Office of Equal Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and Disability Services Department (EAD) to ensure she met the people who would be handling her accommodations. She had been told by a friend in high school the importance of ensuring her college would be able to meet her needs.

Grace said that without that guidance from a friend, she would not have known how to go about working with the accommodations office. While information about Student Access Services, formerly the EAD, is included in welcome week materials and many professors mention accommodations in their syllabi, it is largely up to the students to recognize the services they need and seek them out on their own.

“A lot of students come to us already knowing they need us,” Tiffany Culver, a services coordinator in the Student Access Services office, said. “They have dealt with receiving accommodations K-12 in some way shape or form and so they know they figure they need us for secondary education. They find us on the school website and, as early as spring semester for the upcoming fall, we start getting freshman or new student documentation.”

It’s not at all accommodating for the students. It’s accommodating for the staff and that’s not who it’s meant to accommodate.

Self-advocacy is a running theme throughout the Student Access Services’ practice. Culver said that in the K-12 system, many students’ needs are met by a team of parents, teachers and licensed professionals who work together to design the student’s accommodation plan, without much student involvement or impetus. In college, however, she said the SAS can’t know a student needs them without the student first speaking up and making their needs known.

“You need to speak with your professors about your needs in the class, have that dialogue with your professor, because the professor may be able to do things a different kind of way. You never know until you speak to your professor about it,” Culver said. “That’s the foundation we’re trying to build, the comfort and confidence in discussing your condition.”

Grace felt as though the expectation of self advocacy from the outset was difficult. On top of transitioning to college, students with disabilities are expected to juggle navigating a new and often unfamiliar accommodation system. For students like Grace, whose disability affects her communication and executive functioning, it feels like Vanderbilt expects students to arrive with a set of skills they have not been taught before.

“If the Student Access Services could take more initiative to give everyone an equal understanding and if they would act as a liaison and be more involved it would, I think, take a lot of stress off of students and a lot of miscommunication would not happen between students and professors in their office,” Grace said.

While the university champions the idea of teaching students to advocate for their needs, both Max and Grace said the expectations placed on students, on top of all the pressures students who don’t need services go through, are barriers to their ability to succeed.

“Imagine if you’re a student with some sort of anxiety-based disorder or something like that and they’re putting a lot of pressure on you,” Max said. “Especially students that have a lot of trouble with communications, the entire system is built around you having to [write] a ridiculous number of emails just to get the accommodations you deserve. That’s going to really create a roadblock for you. It’s not at all accommodating for the students. It’s accommodating for the staff and that’s not who it’s meant to accommodate.”

A Compliance Mindset

Disability is a federally protected class and therefore carries with it a number of obligations that institutions must fulfill in order to remain compliant with non-discriminatory laws. To Grace, these legal obligations often turn into a checklist for the people she interacts with, and they end up focusing on meeting compliance rather than her needs as a student.

“Any time legality is brought into things, it gets messy and complicated,” Grace said. “People are more concerned about following the strictest guidelines that are written in the law of something. They really forget the needs of the person or how to interact with the human.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the 1974 Rehabilitation Act requires the university to provide the reasonable accommodations to students with medically recognized needs. These accommodations are processed through the Student Access Services office, formerly Disability Services under the Office of Equal Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and Disability Services Department, which in January split into three separate offices.

In order to receive accommodations, students are required to complete two forms: the new student registration form, which is completed only the first time a student registers for accommodations with the office, and the accommodations request form, which students fill out every semester and which details the specific accommodations they are asking for in their classes for that session. In addition to the forms, students must have medical documentation of their disability which indicates that “the disability substantially limits a major life activity.” To Max, the process of having to reapply for what are largely the same accommodations every semester is burdensome.

“I should just be at most having to send them an email that says I’m keeping my accommodations from last semester,” Max said. “That’s it. That’s all I should need to do.”

After students register with office, they’re given an accommodation letter which details the supports they are allowed for class. Culver said that letters are sent by email with students’ professors copied as a means of providing a sort of ice-breaker between the student and professor. However, Culver also said SAS encourages students to meet with their professors one-on-one to talk through accommodations and to practice advocating for themselves.

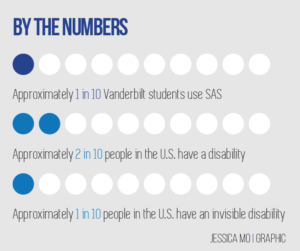

According to Culver, around 10 percent of undergraduate, graduate and professional students receive some sort of accommodation through the office. Services include supports like extended time on tests, distraction-reduced testing environments, notetakers, access to recorded textbooks, sign language interpretations, adaptive technology, etc., as well as housing and dining accommodations.

At the moment, the university does not track the breakdown of which services are most utilized, or how many students use testing accommodations or notetaker services versus housing or dining accommodations. According to recently hired SAS Director Jamie Bojarski, the office is currently doing a lot of their work on paper and spreadsheets.

She plans to implement a data management system in the next year or so to both keep better records of who receives what and to streamline the accommodations request process that students go through. Her hope is that students would not need to repeatedly fill out the accommodations request every single semester.

The current work flow of the office puts a lot of pressure on the staff of five, who handle all approximately 1100 individuals who need accommodations. As a result, it can often take some time for the university to process accommodations requests and get students the materials they need, whether that is testing permissions or accessible format textbooks.

“The new director Jamie, seems really awesome,” Grace said. “She offers a fresh and new perspective at Vanderbilt. Jamie seems to really care about people and what they need. Educating professors and faculty on how to better work with students with disabilities by teaching them how services work, about the laws, and about disabilities. She is definitely a person who holds great potential to change the environment at Vanderbilt for students with disabilities.”

Inclusion, Acceptance, and Understanding

In his op-ed, Stromer noted the irony of Vanderbilt’s robust special education teaching department versus the way disability among students was handled during his time. Vanderbilt is ranked second in the nation for its special education program and for decades has been a leader in disabilities research. Grace said that, while things have improved throughout her time at Vanderbilt, she had expected and assumed the university would have stronger supports for its students who have disabilities.

“It’s just surprising when you compare Vanderbilt and supposedly having the top education program in the country on their campus, how the disability service doesn’t reflect that, and how the campus doesn’t necessarily reflect that,” Grace said. “It’s very ironic to me.”

While initiatives like InclusAbility and improvements at Student Access Services have helped, there is still room to grow for the university. Grace said that many of the difficulties are not things that can be changed by initiatives alone, but by larger institutional decisions to prioritize funding around needs like technology and staffing. Efforts to tackle stigma and awareness are important, she said, but there needs to be attention paid to fully meeting student needs as well.

“Inclusion doesn’t mean that you just treat me like I’m just like you, because I need help in certain things,” Grace said. “So sometimes we try to do that to be inclusive, but it becomes like you’re not actually meeting my needs.”

On a number of occasions, Grace has faced difficulty in classes when professors don’t fully understand what her disability means or she has not had the chance to meet with them prior to the class. Whether that means asking her to participate in a way that conflicts with her abilities and accommodations or expecting her to present her learning in a way that is not accessible, these interactions have hurt Grace’s comfort in her classroom and with her professors.

“[Professors will] ask me to read something out loud, and I can’t do that, so then I have to announce to my professor in that moment and to my entire class why I can’t do that right now which is like not something I enjoy doing,” Grace said. “I’m at a point where I’m okay talking about it, but I can see why for a lot of people that would be absolutely awful.”

Much of the disconnect, Grace said, comes from a lack of understanding about disability and accessibility throughout the university. She said that she has had a number of instances of disappointing interactions with faculty, but she doesn’t feel comfortable reporting those experiences for fear of it impacting her ability to work with professors in her major.

People just don’t know the language to use and don’t feel comfortable starting that conversation.

“The problem with having to communicate with so many different people at the same time is you’re having issues [in the classroom], maybe you are trying to communicate it but it’s not happening, so you go to [SAS], who are supposed to keep [professors] accountable,” Grace said. “But of course [the professors] don’t want to be in trouble and kept accountable like that, so then they look at you like why didn’t you come to me? Why did you communicate with these people without talking to me? Then that creates tension and tensions can affect class and grading and your ability to learn. There’s a lot of emotional tension that can happen that I don’t think people realize that don’t have disabilities.”

Because there has not been a long history of disabilities advocacy at the university, faculty, administrators, staff and students are often ill prepared to have meaningful and inclusive conversations about disability. A large part of InclusAbility and Student Accessibility Advocates’ mission centers around tackling this gap in understanding.

“How can we make the conversation around disability more accessible for students here on campus and faculty? There’s a lot of stigma around it, there’s a lot of apprehension,” Andi DeFreese, president of Student Accessibility Advocates, said. “People just don’t know the language to use and don’t feel comfortable starting that conversation, so we somehow want campus culture to transition to where it’s an okay space to have those conversations, an okay space to open up and identify as having a disability.”

A Sense of Belonging

Beyond instances of missing accommodations or difficulty with faculty understanding, a major concern brought up both by Stromer in his Washington Post piece and by Max and Grace is the physical location of the Student Access Services office. Located in the Baker Building at 110 21st Avenue South, the office is further from campus than many other student focused resources and is housed alongside departments like human resources and campus dining.

While administrators like the current location for the privacy it offers students and the nearby parking, Max, Grace and Stromer all said they feel the location is a show of how the university doesn’t prioritizes disability and contributes to the sense of shame that disability advocates are trying to dismantle.

“It kind of counteracts that idea of pride around disability,” Stromer said. “They’re saying it needs to be somewhere that’s hidden or separate. Another great example that I always give is that if you look for student accountability, which is where students go when they’re dealing with things like cheating or stealing or breaking university policy, that’s located in the second floor of Rand. So why is that not off campus for confidentiality?”

The SAS office houses the five members of the staff, in addition to graduate students and interns that cycle through the office. It is also where students who receive testing accommodations must go to take their exams. The office has a distraction-reduced testing center that seats around 26 students in study carrels, which are monitored by SAS office personnel, both in person and via continuously running security cameras. Some academic departments choose to monitor their own exams, but many students take theirs in the testing center. In September alone, students took 427 exams in the office.

The security camera monitoring allows the SAS staff to carry on their regular work duties, without having to continuously proctor the room. Max said the security precautions make it feel as though the university doesn’t trust students who test in the SAS office.

“The place is just littered with cameras and for God’s sake they don’t do that anywhere else on campus, and it kind of makes you feel like a lab rat,” Max said.

During heavy testing periods or finals, the SAS utilizes extra rooms on the ninth and tenth floors of the Baker Building to accommodate all students. At times, however, there isn’t adequate space for all students.

“My main concern has to do with their policy of scheduling tests. Every single year they run out of space during final exam season especially,” Max said.

Culver said that during these times, the office works with students and faculty to find alternate testing times that may have more flexibility. However, due to the sheer number of students who use the facilities, the office asks that students give them at least two weeks’ notice in order to find rooms. SAS staff is open to discussions of alternate testing locations, but there are a number of challenges, such as the availability of proctors and access to technology, to allowing another satellite testing site that make the process difficult.

The current system, though, Max says puts the onus of the work on the individuals who need accommodations by asking them to act as the liaison between the SAS office and the professor of the course for which the student needs flexibility in testing.

“There are ways to work around this issue without making students bend over backwards to get what they legally deserve–what they morally deserve, but what the school is legally required to do for them,” Max said.

It’s not, however, just a bigger testing center or a more convenient location that students are seeking. DeFreese said that her organization has for years been advocating for the creation of a disabilities cultural center on campus, where students can not only have their legal accommodations met, but can also work with other resources that are more tailored to their needs and celebrate pride in disability.

“Other aspects of diversity have spaces and places where individuals can feel safe, can have comfortable conversations, but also access to the simple resources they need, such as the BCC or the Women’s Center,” DeFreese said. “So we’re looking for something where disability can not only be a concept where ‘oh I need services so I go to SAS,’ but a concept and culture on campus where ‘hey this is something I can celebrate or something I want to learn more about’ or ‘I’m an ally to a friend of mine who has a disability and I want to help them,’ to as simple as ‘I need a Braille printer and where can I find that.’”

Beyond being a place of pride, Grace said that a center could help students find more targeted resources, like writing tutors trained to work with students whose disabilities inhibit their ability to write or liaisons who help students new to the university navigate the accommodations process.

“I think one of the biggest things for me that could improve is, not even taking into account the campus as in students, but just faculty, staff and the disability office is having an on-campus place to go to take tests but also to get more specific help,” Grace said. “Like going to the writing center hasn’t been sufficient for me because they don’t understand what my struggles are with language and with writing, so they’re not really able to help me. So then I don’t really have people that can actually help me, and I’m kind of stuck.”

Stromer, Max and Grace all said they felt encouraged by the InclusAbility programming and the attention Vanderbilt is paying to disability this year. Other initiatives, like making physical accessibility a priority in FutureVU planning, are indicative of a growing administrative effort to address students’ needs more fully.

Still, there is a lot of work to be done, both in terms of dismantling stigma and smoothing out the compliance-side issues. Many of the problems Stromer brought up in his Washington Post piece remain prevalent on campus.

“Having the SAS be in a more inclusive space, I don’t actually doubt that that will happen at all,” Stromer said. “I think when you look at our peer institutions, it’s already happening and I think that it’s going to get to the point where it’s going to have to happen because it’s an outlier right now. What I see happening, and what I think and I hope–I actually felt the same way about all of the points I raised–I think all of these changes were coming, but I really wanted to make sure that this wasn’t something that happens ten years down the line.”

Graphics by Jessica Mo. Grace Allaman contributed to this report.