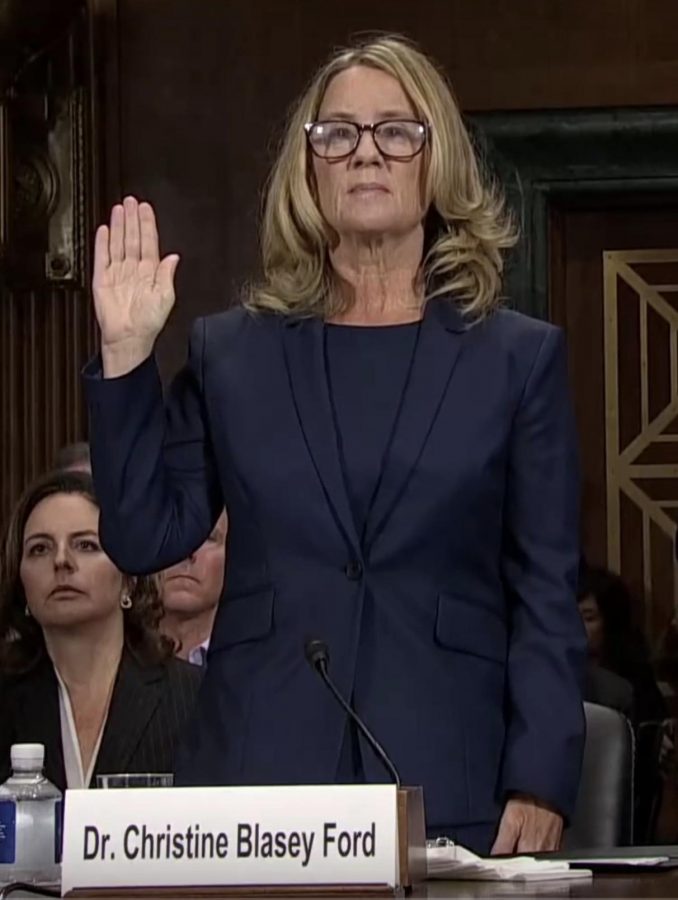

This past Thursday, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the nation, claiming that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her when the two were in high school. Over the course of 15 minutes, she told us how she was sexually assaulted when she was young, how she kept this secret bottled up for more than three decades and how she was threatened and shamed once she came forward. During those 15 minutes, her voice cracked. She fought off tears. Retelling her trauma was so exhausting that she requested caffeine.

After Ford finished her opening statement, she was questioned. But she wasn’t questioned by the 11 male, majority-party members of Judiciary Committee. She had to go head-to-head with sex-crimes prosecutor Rachel Mitchell. To contrast, when Kavanaugh was questioned about his testimony, he talked almost exclusively to senators.

When women come forward, we seek to falsify

When Ford came forward, she was interrogated by a prosecutor, even though she was not on trial. When Kavanaugh was questioned, he was placed in front of colleagues, even though he is seeking a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court.

It seems that we seek a higher threshold of evidence to believe a woman’s story than to believe a man’s story.

When women come forward, we seek to falsify: What was she wearing? Was she drinking? Does she have another motive for coming forward? It’s why Kavanaugh and his defenders were able to claim that Ford’s testimony is the product of a conspiracy between Democratic dark money and the media. Women’s testimony always needs to survive even the most inane outside explanations.

But when men push back, we look to corroborate: He’s a good guy–he’d never do something like that. We see this in Kavanaugh’s restructuring of his high school self as a pure, Catholic-school boy. He knows that if we see him as a good kid, we can’t see him as a rapist.

We also seek to change the threshold for punishment, but only to favor men. While Kavanaugh’s confirmation process is really just a job interview for a court seat, many have sought to increase the standard of guilt to a judicial level, “innocent until proven guilty.” Even though the employer (the Senate) could reject him on Ford’s accusation alone, Kavanaugh’s defenders are pushing a “reasonable doubt” mark to reach. And that’s not possible with a day of hearings and a one-week FBI investigation. Ford would need damning evidence and Kavanaugh would need a pathetic retort in order for us to convict him of a crime. But that’s not what the hearings are for.

The same goes on college campuses. The threshold of guilt in sexual assault cases used to be “preponderance of evidence,” because investigators don’t have the resources to reach a higher bar and the accused is not looking at criminal punishment. But Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has since raised the standard, seeing it as not granting enough rights to the accused. But when 91 percent of colleges report that there are zero rapes per year at their school and one in four women report being assaulted, the focus should lie with helping women.

How we react to the Kavanaugh hearings has consequences for survivors.

Helping women means listening to the stories they have been brave enough to share without the assumption that they have ulterior motives. It means not viewing Ford as a ploy of the Democratic Party, but rather as citizen of this country who drew the line at her perpetrator being nominated to the highest federal court in the United States. It means looking deeper at Kavanaugh’s volatile behavior during the hearings, not dismissing it as an unintended consequence of a high-stakes situation. It means understanding that Ford remained poised and cooperative under the same set of conditions after revealing her trauma to the world.

How we react to the Kavanaugh hearings has consequences for survivors. The survivors in your classes, on your floor, in your campus orgs. We cannot dismiss Ford’s experience because of the time that has elapsed since it occurred; rather, we have to support her in this retelling, no matter how late we may think it has come. Because if we don’t — if we cast doubt rather than extend compassion — we promote silence. We allow perpetrators to live without facing consequences. We allow them to go to Yale, to teach at Harvard, to be appointed to the Supreme Court. If a survivor has a story to tell, they need to know that we will listen, not set out to prove them wrong.

In any dispute, both parties’ claims should be weighed equally. But when it comes to sexual assault, we give men more chances to explain than women. We give them more benefit than doubt.

Anonymous • Oct 2, 2018 at 8:22 pm CDT

If we systematically believe every woman who came forward with claims of sexual assault, then anyone could claim sexual assault, we would always believe him or her, and the accused’s life would be ruined by a lie. Eventually, though, people would recognize that there is no legitimacy behind the claim. Then it would be like crying “wolf.” And when there is really a wolf, people would not believe that cry anymore. I fear that accepting Ford’s claims completely without doubt in the face of the fact that there is no definitive corroboration puts us on the track of turning claims of sexual assault into cries of “wolf.”

An independant thinker at Vandy • Oct 1, 2018 at 11:37 am CDT

“We give men the benefit of the doubt, but hold women’s testimony to the highest possible standard”. Let’s reword that statement without labeling the gender of the two parties: “We give ‘the accused’ the benefit of the doubt, but hold ‘the accuser’s’ testimony to the highest possible standard”. This is actually how our justice system is SUPPOSED to work. We give the accused the benefit of the doubt until the accuser’s evidence is sufficient that the accused has been proven guilty. I.e. innocent until proven guilty. If we always trust the accusers without scrutiny, we would be back to the chaos of the Salem Witch Trials. There is no denying that the sexual assault of women is a major and tragic problem. And further, victims of such crimes deserve justice and support. However, justice should only be served once the accused has been proven guilty. Otherwise, a false claim turns the accused into a victim. In this current climate, if someone is falsely accused, they lose any chance of having a successful life, employment, etc., just as if they did commit the crime. Back to Kavanaugh, he has not been proven guilty yet. Thus, we should not treat him as guilty yet. Who knows at this point what the outcome of the investigation will be. But until that point, we should consider him innocent while ALSO being supportive of Ford. It is perfectly reasonable to support Ford (or any accuser) without prematurely condemning Kavanaugh (or any accused person).

Independent and Sane • Oct 2, 2018 at 4:13 pm CDT

The thing is, the process that Kavanaugh is going through is not the justice system. He has not been charged with a crime. Presumption of innocence (or “innocent until proven guilty”) is a legal right of the accused in a criminal trial, not in the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing for the determination of a nomination to the Supreme Court. Brett Kavanaugh will not be imprisoned or otherwise punished due to not becoming a Supreme Court Justice (now, whether or not he is charged of sexual assault or perjury after this is over remains to be seen).

All that this congressional process is, is a determination of whether or not Brett Kavanaugh is worthy of sitting on the highest court in the land. And from what we’ve seen, the answer is no. Kavanaugh is partisan, temperamental, and lied repeatedly under oath — even about trivialities that likely would not affect the result of the hearing. He said that the event has already been investigated — false. He said that all four witnesses “say it didn’t happen” — false. He said he has never experienced any memory loss of any kind due to alcohol consumption — false. The list goes on. And on.

Honestly, the zealous partisan defense of Kavanaugh is astounding and appalling, as is the Senate’s hypocritical attempt to rush Kavanaugh’s confirmation without time for the people of the United States to let their voices be heard or for the FBI to complete a comprehensive investigation. This hearing is a symptom of the polarization that has plagued the United States in recent years and neither side will benefit.

Man with the Axe • Oct 13, 2018 at 9:45 pm CDT

When any kind of decision must be made and there are conflicting stories to sort out, do you automatically believe the story of the accuser? Why would you do that? Are accusers more truthful than accused persons? I can’t see any reason to believe that.

You are confusing the criminal trial standard of “guilt beyond a reasonable doubt” with the “presumption of innocence.” No matter what the proceeding there must be a presumption of innocence. For one thing, proving a negative is close to impossible most of the time. In this case, Kavanaugh is asked (by you) to prove that he didn’t assault Ford even though he has not been told the date of the attack, the location, who owned the house, who was there (and admits it), how she got there or how she got home, or who invited her. She did not originally state that the attack happened in 1982, but rather in the “Mid 1980s.” How in the world is a defendant supposed to carry a burden of proof under such circumstances?

To give you a counter-example: Suppose a young black woman is applying for a job with your company. Her record shows a single charge of, say, embezzlement, but the charges were dropped due to lack of evidence. Do you disqualify her from the applicant pool or, alternatively, treat the dropped charge as meaningless because there is no evidence to substantiate it? Do you find this case tougher because the accused is not a white male from a privileged background, and so your prejudices cut the other way?

C. Sense • Oct 1, 2018 at 11:13 am CDT

You absolute morons. We don’t seek to falsify, we seek to

Verify. this is not a standard of beyond a reasonable doubt. Rather, it is acknowledging that every single one of her witnesses has no recollection, and she has no corroborating evidence. This is not even a case of he said she said. It’s even weaker. We don’t throw away the individul in the name of the collective.

Articles like this are intentionally divisive. They say you stand with all women or you’re pro rape! You believe all women or you think they should be second class citizens. What absolute garbage.

You can say I stand with survivors, and that this needs proof. This is the same herd mentality at Duke lacrosse, at UVA, etc and ultimately does more damage to survivors by dividing and labeling