At 11:30 p.m. Thursday, I was startled awake by my roommate busting down the door with a grin and asking whether I planned on listening to the new “T Swizzy.” Unclear on who “T Swizzy” was, I hopped on Spotify and started frantically searching for whatever underground rapper I was clearly not doing my homework on. When Spotify yielded no results, I went straight to Instagram and hit the same exact dead ends.

The more little I found, the more desperately obsessed I became. Was T Swizzy completely off the grid? Was he potentially down for an interview? What kind of music did he make? “T Swizzy” sounded a lot like the moniker slapped onto a nascent middle-school rap prodigy not allowed to have any social media accounts yet. To have your rhymes travel nationwide by just word-of-mouth at 15 years old was a feat that impressed me way more than the boring readings sprawled out across my desk. I was going to find out who this “T Swizzy” was. And if it was the last thing I did, I was going to listen to his new mixtape.

This motivation lasted until, still not being able to take a hint from my roommate’s sarcastic laughter, I was even further awakened by loud noises coming from directly outside my door. On a floor that seems to have hosted spontaneous parties nearly every night since fall break, the past few weeks have seen me become sort of a grumpy old man: when all of your classes are simultaneously making the dreaded ramp-up towards hectic final projects, and you’re so behind that you flinch every time a professor utters the B-word, the last thing you want to hear while struggling through an essay is your neighbors blasting loud music from some generic party mix on shuffle. But once I was able to make out a muffled “Taylor Swift” from the commotion, I knew two things: (1) exactly who “T Swizzy” was, and (2) exactly what kind of party was happening tonight.

Because hardcore gonzo journalism on an impromptu Taylor Swift listening session is always more interesting than the multiple essays you have due, I immediately sought to find the source.

“Where is this T Swizzy listening party being held,” I texted my roommate. Upon getting the news that it was at the very end of the hall, I threw my tape recorder into my pocket and set out to make the trip.

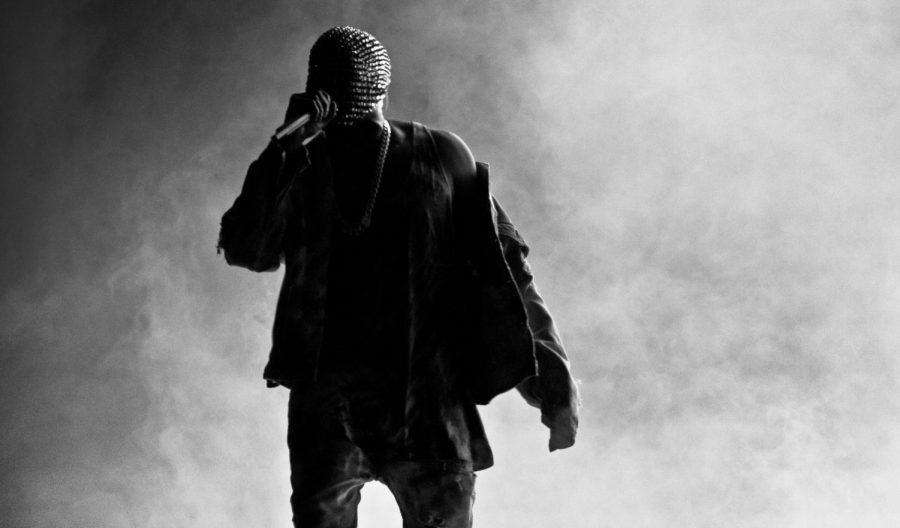

Taylor Swift’s voice got louder and louder as I walked past giddy revelers. Halfway down the hallway, my roommate stopped me to offer a good-hearted warning about interviewing the host mid-song. The only pretext I was offered was that “she’s pretty locked in right now.” As a longtime Kanye West fan, I was already quite terrified by the implications of attending a Taylor Swift listening party alone, surrounded by Swifties, without any means of backup or self-defense. As I ventured further and further down the corridor, my feet getting heavier with every step, I was increasingly tempted to turn back. Before it crossed my mind to call and tell my parents I loved them, I saw my fist knocking at the door.

The last listening party I attended consisted of a borrowed “Alexa” speaker, a shared bag of lukewarm popcorn and two hours of new Kanye West music to contend with. Interestingly enough, tonight’s Taylor Swift celebration was being held at the exact opposite end of the same floor. It’s a fitting visual for the longtime rift between both musicians: not only are they almost complete contrarians from a sonic standpoint, but the few times that their tumultuous connection has crossed personal boundaries, it hasn’t been pretty—whether by means of viral acceptance speech interruptions, disputes over nude likenesses being used in music videos or countless legal impasses.

One of the rare pieces of common ground between West and Swift, though, is that each have waged longstanding public battles with an ever-exploitative music industry. Whereas West’s gameplan last summer was to blitz Twitter with demands for execs to fly to meet him immediately, leaked phone numbers and videos of him urinating into Grammy trophies, Swift’s different approach was the premise for tonight’s gathering: one by one, she’s been re-recording albums owned by malevolent industry insiders, with the ultimate goal being that those who spent years profiting off of her work will never make another penny from it again.

When I finally staggered into the party and asked whether anyone would be down to chat with The Hustler, all 10 or so pajama-clad attendees immediately pointed at first-year Emma Bufkin.

“That would be your girl,” her roommate Alli Hoying said, before offering hot chocolate and pointing me towards a spot against the wall.

If I wasn’t scared before, I was definitely scared now. For the first five minutes or so that I was in the room, I did not see Bufkin’s face. Seated criss-cross-applesauce directly in front of a television screen on her desk, there seemed to be a religious telekinetic connection between her and the lyrics that were coming in and out of frame on the YouTube video being broadcasted—drifting between entranced sways, outstretched arms and something that looked like interpretive dance, she would occasionally jolt upward and shout one of three things: “That was different,” “This is everything I ever needed in my life” or, through bitter tears, “That completely sucked.”

“Her first album came out when I was four years old,” she said, when I tried to squeeze in as many between-song questions as I could before they would cue up the next visual. (Bufkin was opting to watch every single YouTube lyric video in order, rather than just listen on a streaming service, because “that’s the way Taylor intended it.” She also had most of the tracklist memorized.) “I own nine Taylor Swift shirts and one sweatshirt. I just need my ‘Speak Now’ shirt and my ‘Evermore’ shirt and then I have every shirt from every one of her albums.”

There is a certain mystique with Taylor Swift that, even from the perspective of someone who spent years listening to practically everything but her, thickens the air with a sort of inescapable legend. In one of the only moments I remember from Vanderbilt Visions this year, for instance, my VUceptor told our group about a fabled high-rise apartment Swift is rumored to own in Nashville.

“When the light is on, it means she’s home,” he said. Half the room gasped, and the other half frantically whipped out cell phones to find the apartment on Google Maps.

Although I am by no means a devout Taylor Swift fan, I’ve come to realize over time that for a majority of the artists I even listen to in the first place, there is some sort of cultural line that can be traced directly back to her. Whether Kanye fans like to admit it or not, her feud with West played a significant role in the trajectory of his career. Being able to battle her for the #1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 went several lengths in warming A$AP Rocky to audiences beyond just those of East Coast hip-hop. Even when the disgraced pharmaceutical conman Martin Shkreli was making waves for owning the only copy ever to exist of Wu-Tang Clan’s “Once Upon a Time in Shaolin,” despite being seemingly completely unrelated, there she was, in the headlines. There isn’t a long list of modern-day musicians you can credit similar omnipresence to. I don’t listen to Taylor Swift. But there is no way I—or you—can justifiably fail to respect her footprint.

When, while asking for a rundown on the album’s context, I worked up the nerve to utter the name “Kanye West,” the room paused as if I had said a slur.

“You need permission from the songwriter in order to use their music,” first-year Logan Glazier said, looking past my slip-up as Bufkin sat in shock. “So they still need permission from Taylor Swift now, but she’s gonna give it to them, because why wouldn’t she—she wants to make at least some money, right? But now, when she re-records the new stuff, they’re gonna go to her on the original track first—but now the difference is that she can say no and give them the new re-recorded version that has no rights from the record company.”

“Scooter Braun was Kanye’s manager when Kanye was trying to, like, ruin Taylor Swift’s career,” Bufkin said. “And now Scooter Braun owns the rights to all her music, which is, like, awkward, because he single-handedly tried to destroy her whole career.”

What gave tonight’s listening event a crucial touch was that, on top of the already-important pretext of new Taylor Swift music, there was the added stipulation that if you considered yourself a real fan, these new tracks were meant to definitively replace the old ones. Every stream of an original version was another dollar in Scooter Braun’s pocket—and it was either the songs were permanently improved, or permanently ruined (and therefore low-key erased from history).

This puts hardcore fans of Taylor Swift in a tough spot. At one point during “All Too Well (Taylor’s Version),” for instance, I watched as a slouching Bufkin muttered heartbroken criticisms and shook her head in disbelief. As she frustratedly pressed her face against the drawer in front of her, everyone in the room sort of thought she was joking.

“Make sure you put that in the article,” first-year Tommy Pennington said, as Bufkin continued to lament about how the song sucked. The group of friends (and de facto emotional support network) immediately surrounding her let out a nervous laugh. Then, upon seeing her pull her head back from the drawer after a few long seconds, they frantically hand-signalled towards Hoying to indicate that she was crying.

“It’s alright,” first-year Angela Charles said in a last-ditch attempt to console Bufkin. “I thought it was good!”

“Good for you, Angela, we’re having a breakdown!” fellow first-year Kathryn Tam shouted in response.

“I don’t like this one,” Bufkin sobbed. “I wanna- (unintelligible because of sobs). I don’t like this. I don’t like this.”

“She likes the original one better than this one,” Hoying said as I looked on, unsure of what I was dealing with. “So she’s upset about that.”

After a few seconds, though, she picked up the remote as if nothing happened, and went right back to scrolling through the array of on-screen music videos for whichever one was next on the tracklist. With 25 songs left on the LP, it wasn’t like there was any time to waste: she and her roommate’s classes were slated for 8 and 9 a.m. It was already past 1.

Over the remainder of the session, the listening party began to look a lot less like a group of fans consuming a new album collectively, and more like a group of supporters cautiously observing Bufkin as she intensely observed the television screen. One by one, revelers trickled out, citing early morning lectures, drowsiness and hunger before bidding everyone farewell. Several times, Bufkin vehemently assured Hoying—now semi-sleeping on a couch—that if she wanted her to stop she could, to which Hoying would drowsily reply that there were no worries.

One of the final songs played before we reached a stopping point was “Ronan,” the hard-hitting tearjerker Swift dedicated to a young fan lost to cancer. Bufkin spent a long while prefacing the track’s intensity, emotionally preparing herself whilst rejecting my assurances that if she needed space, I was happy to leave. The four minutes and 40 seconds that the video occupied was the most deathly silent the room had been since I arrived. When it ended, and neither myself, Hoying or Bufkin dared to utter a word, the only sound audible on my tape recorder was the pushing of remote-control buttons in fervent search for the next video.

Sitting there against the wall, staring at the television as the lyric video faded out, I couldn’t help but ask myself: as someone whose job it is to speak on music, when was the last time a song made me shut up?

The explanation, and one that has been true for her entire career, is simply that Taylor Swift has the capacity to suck all gravity out of a room. I unfortunately know this firsthand: gravity was apparently so upset at its ousting, that it kept me pressed to my bed all throughout the five alarms that were supposed to wake me up for class the next morning.