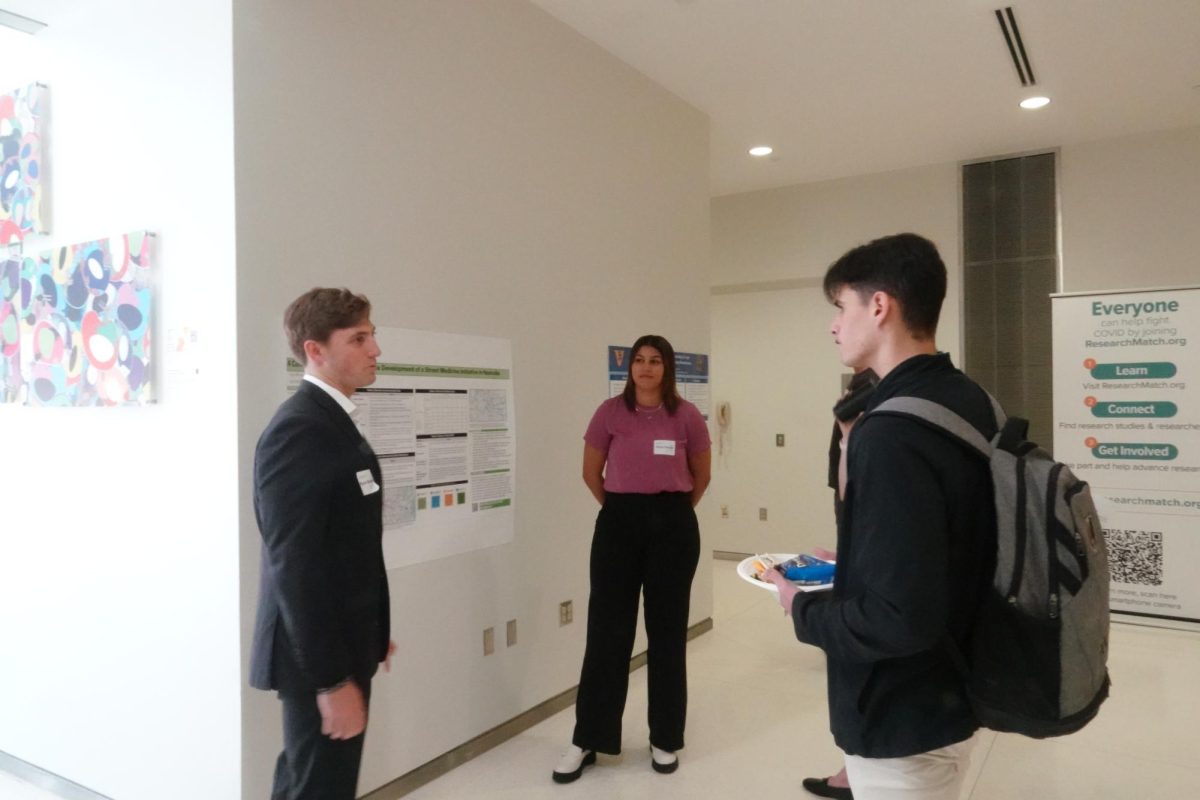

Students hosted Vanderbilt’s inaugural Homeless Health Conference on April 13, bringing together local non-profits, medical professionals and community stakeholders to discuss combatting homelessness in Nashville. Titled “Future Physicians as Advocates: Creating Collective Impact from Community Voice,” the conference focused on building coalitions between both aspiring doctors and advocates to address the homelessness epidemic and included sessions on the landscape of homelessness, an exploration of street medicine and a narrative medicine workshop with medical students working in homeless health.

Sophie Druffner, a second-year Vanderbilt Ph.D. student in community research and action and director of the Housing, Opportunity, Policy and Education (HOPE) Lab, helped organize the event as the research director. She described some of the conversations that led to the conference’s roots.

“Some students who were interested in homeless healthcare and I had a conversation about how we could get more people talking about the issue or even just to know it exists,” Druffner said. “Specifically, the people who are going to have a lot of power once they have their MDs and even have a lot of power now as students.”

Junior Brina Ratangee, the student chair of the conference, mentioned the importance of recognizing that different areas have unique assets and challenges when it comes to addressing the needs of unhoused populations. Ratangee also serves as the News Editor of The Hustler.

“Having worked with our unhoused neighbors here in Nashville through providing blood pressure screenings and publishing their narratives in ‘ayu: A Narrative Medicine Journal,’ I recognized the rich tapestry of efforts Nashville already has working to combat homelessness and wanted to introduce these directly to students who intend to enter spaces of clinical care” Ratangee said.

Bobby Watts, CEO of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, gave the opening keynote presentation. Watts addressed the power of healthcare advocacy with homeless populations at an individual and institutional level, especially for those working in street medicine.

“One of the great things about the health care for the homeless community is that we are a vessel, a vehicle to help facilitate peer learning and learn together about how we can do things better,” Watts said.

Watts also emphasized that students have power to advocate for change.

“Yes, our system is bad, racism runs through it, inequity runs through it,” Watts said. “Use your power and your responsibility that comes with that power to effect change, as future physicians, as physicians, as students. You have the power to be effective and change-making advocates.”

The two panels following Watts outlined the landscape of homelessness in Nashville. One, called “Life Essentials,” discussed the trauma in homelessness and the retraumatization cycle often experienced by unhoused people in Nashville because of the lack of consistency in grant funding. The other panel discussed the additional obstacles faced by survivors of domestic violence, queer and transgender young adults and people who were formerly incarcerated.

After the panels, Dr. Jim Withers, founder of the Street Medicine Institute, spoke over Zoom about the importance of empathy, solidarity and compassion when addressing health disparities in homeless populations. He also discussed his personal journey of recognizing these inequities through his “classroom of the streets.”

“[Those on the street] would be described as ‘those people, they’re just drug seekers,’ ‘those people, they just don’t want to take care of themselves,’ ‘those people are not compliant,’ ‘those people won’t cooperate, so what can you do?’” Withers said. “When I began hearing that kind of language, it startled me a little bit, but then I turned my diagnostic lens around to the people around me, the teachers and those saying, ‘What’s wrong with these people?’ And so the health system became my other big patient.”

The final session featured two panels, one focused on addressing homelessness by working within the system and the other centered on how homelessness can be addressed in unique ways outside of direct outreach, specifically for faith-based organizations.

The conference closed with a keynote from Dr. Jennifer Hess, director of Vanderbilt Homeless Health Services, on the power of the conference as a whole.

Sophomore Ellie Armstrong, HOPE Lab outreach coordinator, spoke to the importance of Vanderbilt students getting involved in the field of homeless healthcare.

“Tennessee is one of the most hostile places for unhoused individuals to live in and we, as privileged people, have an obligation to support those who may not be able to support themselves right now,” Armstrong said.

Another member of the HOPE Lab, sophomore Scott Cho, described the conference as “inspiring” and “motivating.”

“To see the thoughtful engagement helped me be hopeful for not only the future of Vanderbilt Homeless Health Services, but the community and sense of collaboration the individuals at Vanderbilt can foster and communicate to the greater Nashville area,” Cho said.

First-year Will Kuhlman, a conference attendee, said he enjoyed the “diverse perspectives” and appreciated how the event broadened his understanding of what care for the homeless looks like.

“Street medicine is an idea relatively new to me and presents an intriguing new way to treat patients and access disadvantaged populations,” Kuhlman said.

Hess described the process of delivering healthcare to those living on the street as “transformational learning.”

“It [delivering street medicine] changes us,” Hess said. “We then bring that empathy back into our practice and become better doctors and better advocates.”