Located in the old Downtown branch of the United States Post Office, the Frist Art Museum has been a staple in the Nashville art scene for the last 23 years. Providing a voice for artists all around America through their rotating exhibits, it could be argued that the Frist’s magic is rebirthed every season, as you will never see the same art twice within their walls. Currently, there are three major exhibitions taking place, with two on the first floor, “Southern/Modern” and “Carving a New Tradition” and a new sculpture exhibit named “Monuments and Myths” on the second, providing two different worlds of experience separated by only a few sets of stairs.

The Frist is open Thursday through Monday and admission for college students is $10. On Thursday evenings from 5-8 p.m. CST, college students receive free admission and are encouraged to engage in the frequent artist talks and events scheduled during those evenings. Just a straight-forward, 30-minute walk from campus, the museum allows students to engage in the unique and changing art world. We explored its galleries and exhibits to give students a taste of what they can expect to see there this spring.

“Southern/Modern”

As you walk in, the Ingram Gallery sits straight ahead past the atrium, housing “Southern/Modern.” The exhibit is the first of its kind, focusing on paintings and paper artwork created from 1913 to 1955 in the South. The aim of the exhibit is to illuminate an often-overlooked region in American art history and showcase the importance of Southern art as a response to racial injustice and class division in the region.

A powerful piece on display is James A. Porter’s “When the Klan Passes By.” Painted in 1939 at the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s power in the South, it serves as a reminder of the invasive eye of white supremacy in the homes of African Americans all across the South; seeing the worried look in the child’s eyes as their mother attempts to comfort them, it highlights that not even the child is innocent to the intimidation tactics of the Klan.

“The Driver” by Gregory Ivy provides a more comforting look at life by placing the viewer in the backseat of a car, a hallmark of the rise of American manufacturing in the traditionally rural South. Ivy’s mastery of abstract reality is highlighted by the fact that I understood the subject before even reading the placard. The subject matter looks like a bunch of lines, but it triggered distant memories of road trips to the grocery store every Saturday with my dad, the sun going down ahead of us as the world felt safe and all was well.

Containing countless art movements and swaying from themes of religion to segregation to the landscape itself, “Southern/Modern” paints a beautiful and tragic art history of the South. It gives viewers the ability to step into the past of the region we currently live in, facing the emotions and experiences of artists in the early 20th century.

“Multiplicity”

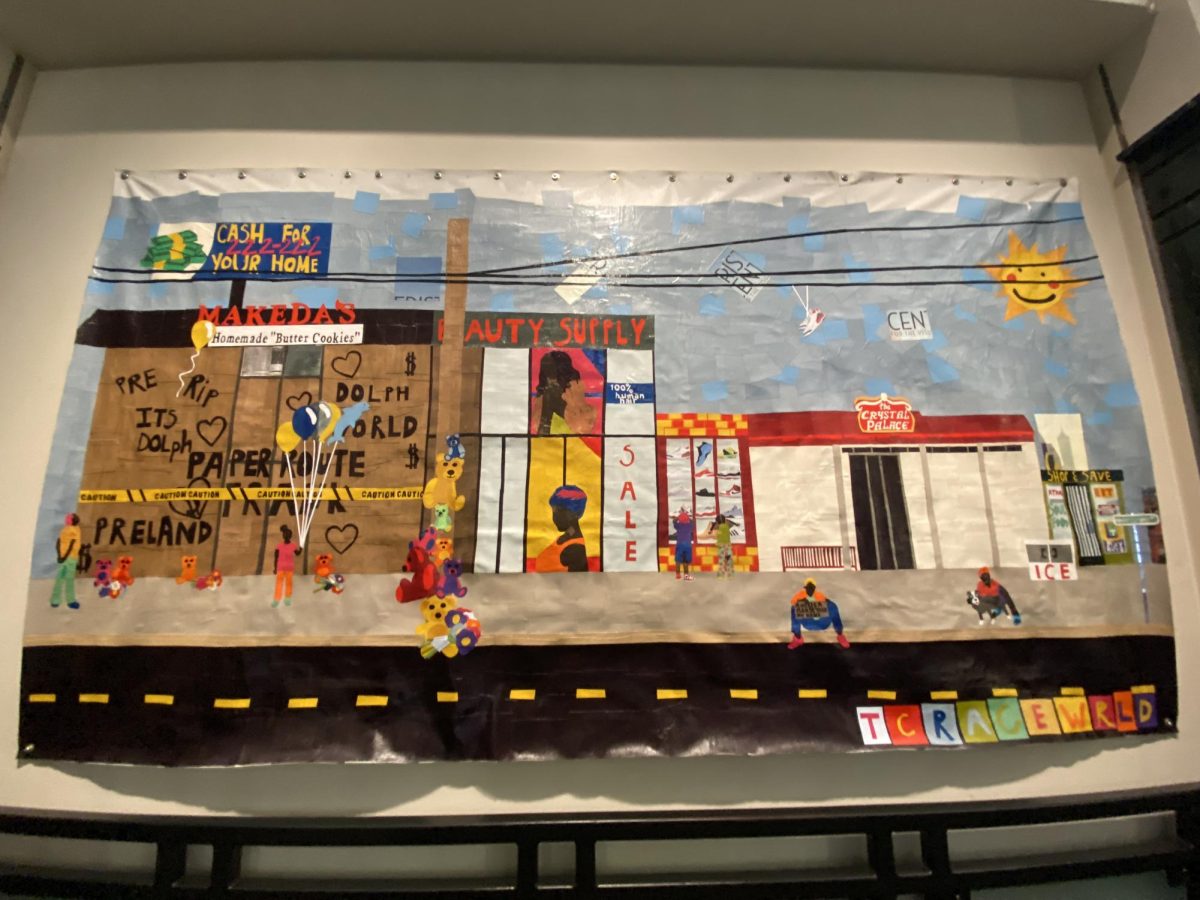

Outside of the gallery, TC Carruthers’ collages titled “Neighborhood Hero” and “Dear Old Memphis” provide the viewer with a glimpse of hope in an environment of hardship. These collages were created in association with the Frist’s previous exhibition, “Multiplicity,” and are now the first installation in “Art in the Atrium,” which aims to activate new art spaces through the Frist’s historic building. Teddy bears and murals line the streets to memorialize the deceased as a man begins a barbeque in his front yard. The murals of Carruthers’ hometown of Memphis show the mourning of community members Tyre Nichols and Young Dolph, victims of violence, as the community tries its best to remain a home for future generations.

“Carving a New Tradition”

Created by LaToya M. Hobbs, “Carving a New Tradition” is a collection of primarily wood carvings that highlight the life of the Hobbs family, but on a wider scale, resemble the lives of many American families past and present. The exhibit was curated by Vanderbilt professor of African American art, Dr. Rebecca VanDiver. Hobbs’ method challenges the traditional form of printmaking by presenting painted print matrixes, which are typically used as a tool to produce prints, as the art pieces themselves.

In these pieces, Hobbs characterizes an experience that is both specific to her role as a Black mother and universal in its depiction of everyday family life. She aims to bring Black families’ lives to the forefront of museums, where they are not commonly depicted. The exhibit’s centerpiece is “Carving Out Time,” which includes five large carved panels that fill the room and transport viewers into Hobbs’ life. Throughout the exhibit, the images of her children playing, her teaching her son on the computer and her husband posing with the children in “Pinnacle,” reminded me of my mother. Being an immigrant mother who raised both my older sister and me, the sense of determination of motherhood is reflected magnificently by Hobbs throughout the exhibit.

Hobbs also provides a peek behind the curtain of motherhood, the times of stress and the necessity of self-care in “A Moment of Care,” which shows Hobbs relaxing with a candle. In carving out both the (literal) mountaintop experiences and lonely nights of motherhood, this exhibit is powerful and immersive.

“Monuments and Myths”

Featuring the works of Daniel Chester French and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the American “friendly rivals” used their talents to sculpt some of the most influential works of art from around the turn of the century. During the Gilded Age, when economic growth led to increased patronage of the arts, the two sculptors produced artwork that contributed to an expanding national identity.

The exhibit was co-organized by the historic houses of the sculptors, Chesterwood and Saint-Gaudens Memorial, along with the American Federation of Arts. The name itself, “Monuments and Myths” calls out both the monumental nature of many of these sculptures along with the way they simultaneously relied on Greek mythology to mythologize American historical figures. The 70 models in the exhibit are often smaller than the statues themselves, which are located across the U.S. and build a nature of grandeur around historical figures like Abraham Lincoln and the Minute Man. Yet, while the exhibit highlights this, it also brings to the forefront the many people, like models and constructors, involved in the process and the narratives that were overlooked.

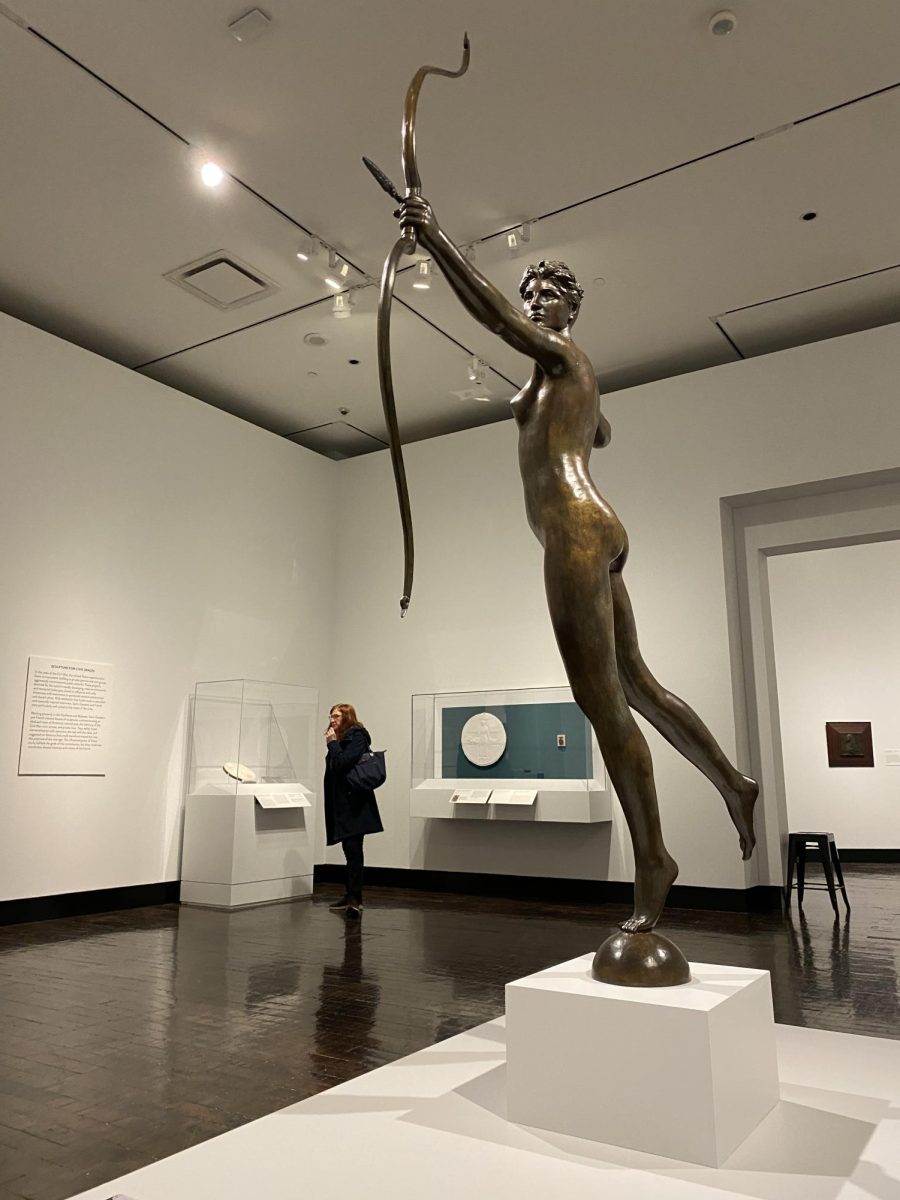

The exhibit is expansive and organized into five sections, beginning with the artists’ studios and ending with the funerary monuments they created. Located midway through, a standout of the exhibit includes a half-size version of “Diana” by Saint-Gaudens, an iconic statue that was featured at the top of Madison Square Garden for decades.

Coming into another section, other significant pieces of the gallery are the Sherman busts, bronze sculptures alongside a bust of General Sherman’s death mask (a cast of the face right after death), that provide a glimpse of both Sherman’s prime years and physical death of the arguably legendary general in the Union Army. Saint-Gaudens’ work goes beyond busts though, extending to the development of the 1906 Twenty Dollar Gold Piece coin; the exhibit presents both the cast model of the coin alongside mint conditions of Saint-Gaudens’ work.

The sculptures also bring in angelic and god-like figures in pieces like French’s “Wisconsin,” a plaster model of the bronze monument that sits atop the Wisconsin State Capitol today. The symbology of the eagle perched on the globe is a detail of the intricate sculpture, tying together the purpose of progress behind the piece.

In the penultimate room, the four sculptures of Abraham Lincoln provide perhaps the most clear view into the career intersection of the artists. Both artists created both a sitting and standing Lincoln, which are located across the U.S., with some being in D.C. and Chicago. Standing in the room, among the many Lincolns, viewers can see the mastery of these two sculptors and the complex American narrative they were helping to create.

Arguably the most culturally significant piece of the exhibit would be French’s plaster model of the portrait of Abraham Lincoln that sits in the Lincoln Memorial today. It felt surreal to see this not-replica replica of one of the most important works of art in American history, knowing it was vital in shaping a national monument. In comparison to “Wisconsin,” “Abraham Lincoln” provides an even greater degree of detail; from the depth between his vest and shirt to the authoritarian gaze on Lincoln’s face, the piece seemed almost life-like for being a plaster model. Another compliment to throw towards French is his attention to detail in carving Lincoln’s hands, showing a sense of mastery in sculpting the human figure down to the last detail. Overall, this piece alone is worth visiting the Frist for.

The current exhibits at the Frist create a compelling look into American history and art across many centuries and regions. With its connections to Vanderbilt and college student initiatives, it is definitely worth the visit this spring.