“We were algorithmically matched with each other in college.”

That’s a new one! Think about it: Have you met a couple who can tell you they left their matchmaking to science and coding? Thanks to a continually evolving algorithm created by a group of Harvard students in 1994, Datamatch has provided an exclusive platform for college students to meet both platonic and non-platonic “friends.” Now, 30 years later, the online algorithm is rapidly gaining popularity, reaching over 40 colleges and matching thousands of students since its debut.

How does it work? The process is quite simple: Each year on Feb. 7 at 12:01 a.m. EST, a campus-specific survey is released based on the university email address you signed up with. Between then and Feb. 14, you can fill out a short (10-15 questions) survey. After that, it’s a waiting game until you are matched with about 10 other students on Valentine’s Day.

By default, Datamatch’s algorithm matches students based on the similarity of their responses to the campus-specific survey questions. However, users may opt to be matched with opposites by choosing the appropriate option on their profile.

Howard Huang, part of the Datamatch team at Harvard, provided us with a glimpse into the inner workings of the unique matchmaking site. As a member of the Statistics team, Huang highlighted the collaborative efforts of various teams — Web, Algorithm, Business and Design — that all play a pivotal role in shaping Datamatch’s success. From the initial paper surveys of 1994 to today’s more developed digital platform, Datamatch has continuously evolved, maximizing its matching capabilities.

Interestingly, Huang noted that the core of the matchmaking algorithm has remained relatively unchanged over the years, still relying heavily on survey responses. Certain features have been added to the site to account for new metrics, but Huang emphasized that the main part of the matching algorithm falls on ensuring everyone gets a reasonable amount of matches.

“Some of the newer things like MBTI, love language [and] Rice Purity Score, were never collected in the past,” Huang said. “But the main part of the matching algorithm that’s very important is that we ensure everyone gets a good amount of matches within their constraints.”

What’s unique about Datamatch is the campus-specific questions that make up the matching survey. A group of campus ambassadors come together each year to submit questions for their school’s survey. For yet another consecutive year, Vanderbilt’s satirical newspaper, The Slant, has taken charge of this initiative. Questions from this year’s survey ranged from “What game do you play during lectures?” to “What’s your favorite type of gambling?”

Guided by insights from Sam Sliman, a senior and Managing Editor of The Slant, questions were designed with a balanced distribution between humor, local flavor and romantic insights.

“We always want to make sure we have a certain number of romantic questions and a certain number of Vanderbilt questions,” Sliman said.

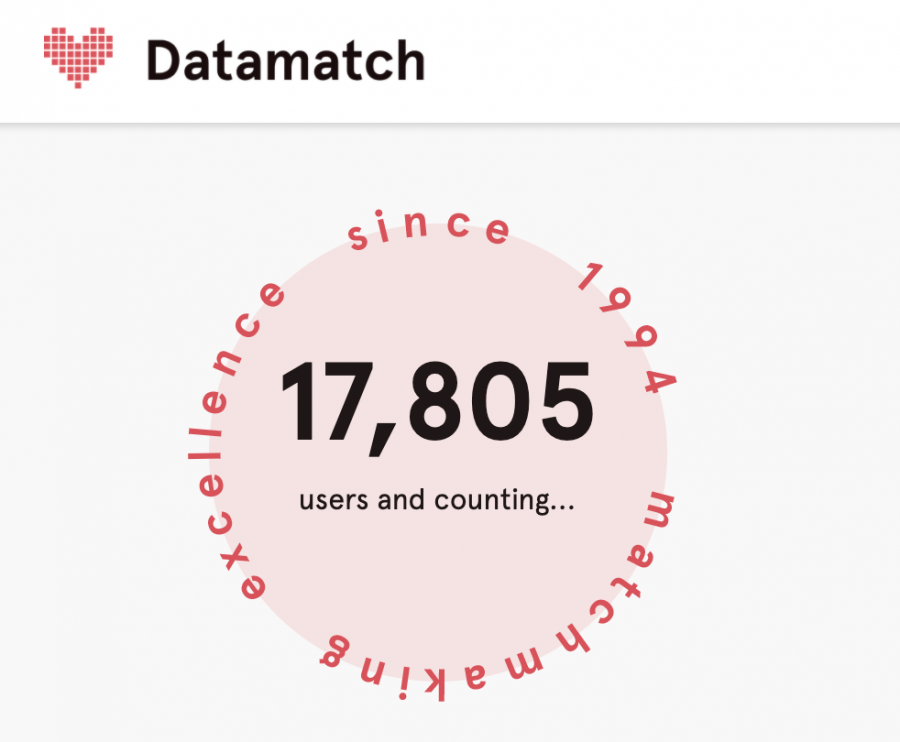

Success for Datamatch at Vanderbilt has historically been gauged by qualitative metrics like the number of student sign-ups — a direct indicator of the website’s reach within the campus community. However, this year’s engagement took a noticeable turn, yielding only 3,101 matches compared to last year’s 5,821 total matches.

“We can usually get about 15% of the school signed up,” Sliman said.

According to Sliman, the drastic change in participation this year was due to the late hanging of posters around campus.

Looking ahead, Sliman shared his aspirations for evolving Datamatch at Vanderbilt, hinting at his interest in pursuing a concept he thought of himself. Collaboration between Vanderbilt ambassadors and the Datamatch team has been relatively limited, permitting involvement only through the design of survey questions. Sliman mentioned his interest in pursuing a humorous original idea where students could opt to match with polar opposites in pursuit of also finding one’s “greatest enemy” but has lacked support from the developer team at Harvard. He noted his desire for more autonomy and creative freedom in the Datamatch process.

When matches were released on Valentine’s Day, we reached out to Vanderbilt students to hear more about their Datamatch experiences, exploring how it has influenced their views on college dating and connections. Jay Lauese, a sophomore, shared her motivations for filling out the survey, highlighting a moment of personal transition.

“Personally, I just recently got out of a long-term relationship and was like, ‘why not?’,” Lauese said. “I think it’s highly unlikely that I will find the one through Datamatch, but it seems like a nice, fun thing to look forward to, regardless of intention. Valentine’s Day is lonely as is. I’ve been on apps like Tinder and Bumble, and honestly, they have overly sexual undertones and are not as appealing as a school-wide match-making site, at least in my opinion. It seems like there are less stakes in [Datamatch].”

Sophomore Matthew McCullough also shared his thoughts on his experience with the Datamatch survey this year. He reflected on his matching outcomes and the nature of this year’s survey questions.

“I found the survey questions to be quite silly; some even made me laugh,” McCullough said.

McCullough went on to discuss his personal disappointment in the actual outcome of the process this year, expressing his wishes for more people to actively participate in post-match contact.

“It’s kind of a shame that not much seems to come out of Datamatch for most people,” McCullough said. “I think it would be really fun if more of us, myself included, actually made an effort to reach out to our matches. Whether for romance or just as friends, it could potentially lead to something worthwhile.”

So there you have it: Datamatch may not be your infallible Valentine’s resolution, but its delicately tuned algorithm certainly has the potential for long-term love. Whether you’re on the hunt for a love that’s mathematically endorsed or just hoping to grow beyond your social bubble, Datamatch offers a glimmer of hope — or if nothing else, at least a statistically-proven shot at not eating another dinner alone. And hey, if this year’s Datamatch cupid didn’t do you justice, the quest for connection isn't over. The Vanderbilt Marriage Pact, designed to help you find “your most compatible marital backup plan on campus,” will soon release its results, giving students another chance at algorithmic love.

You might find your special someone where you least calculate it.