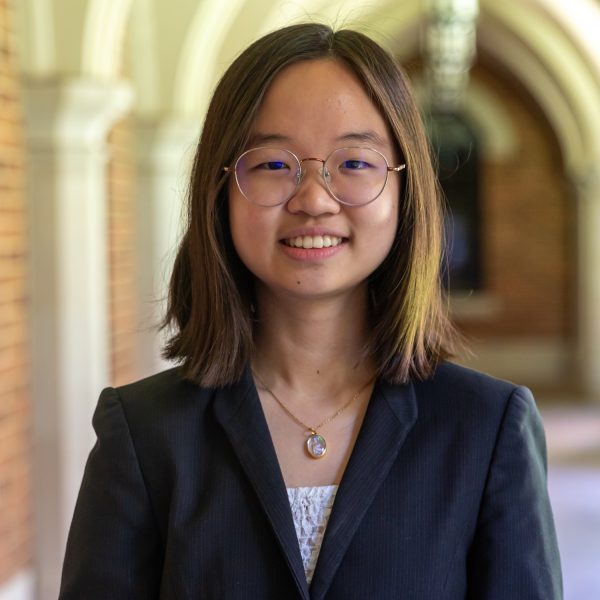

College applications are a biased lottery. From legacy preference to single-digit acceptance rates, college admissions are increasingly becoming a measure of privilege and luck rather than academic merit. Yet, if applying to college is a stressful, time-consuming and unfair process even for American students, imagine how much harder it is for an international student. Unlike my domestic peers, I didn’t attend an American high school or have any friends who were applying to U.S. universities at the same time. While I’m grateful I got into Vanderbilt, receiving my college acceptance feels more like the exhausted triumph of a war general than the jubilant celebration that it should be.

Let’s begin with the Common App essay, which is one of the most heavily weighted components of a student’s application. Picking the right topic for this essay is crucial. Ask any college counselor, current student or online forum, and you will be firmly instructed to pick a meaningful topic that highlights your unique selling points but that does not fall on the essay topic “blacklist.” This blacklist is a list of topics considered overdone, inappropriate or boring, including topics like service missions to Africa and the trauma of a sports injury. The blacklist is an unwritten rule, but it is not an abstract construct — brilliant students have and continue to get rejected because their essays weren’t original or worse, traumatic enough. Why does it matter if athletes talk about how they faced a setback and came back stronger? For that matter, why are college application essays expected to conclude with some glorious inspirational message?

U.S. institutions are largely alone in expecting this level of hoop-jumping from applicants, and it especially hurts international students who do not speak English as their first language. Think about it: if the essay is already a great source of distress for the average American high school student, it feels almost impossible for someone who is not completely comfortable with formal English writing. I applied to five universities in the U.K., and my application took just three days to complete — including the time it took to write and edit my personal statement. Many other countries’ applications explicitly state what they expect to see, such as a certain level of academic readiness or specific kinds of extracurriculars or work experiences. In contrast, demystifying the “holistic” American college essay was a lengthy process of endless Google searches, hours of YouTube videos and countless rewrites of the same points to find the optimal sequence of characters to impress some mysterious admissions officers.

Applying to U.S. schools made me feel like I was swimming against a riptide at every step of my application process. Even my name was a problem. My name doesn’t follow the first-middle-last name format, but the Common App, SAT and Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) exam all require I input my name in that format while ensuring it appears in the same order that it is printed on my legal documents. How was I supposed to do that? In addition, despite assurance from Vanderbilt and other top institutions that will evaluate me in the context of what courses my school offers, I couldn’t help but worry that I’d be at a disadvantage because my school doesn’t compute GPA or offer honors or AP classes. Although universities claim that many components — including AP classes and test scores — are optional, how can I trust that they truly mean it? What if American college counselors have insight into what is truly critical that my high school counselor didn’t? What if all my qualifications are issued in a different language?

These questions were on my mind at every step of the application, and since my high school counselor didn’t have the answers to them, I was left to navigate this confusing and overwhelming process by myself. I did wrangle together some semblance of an answer through the blessing that is the internet, but it is an unfair ask of any student especially during the business of the last year of high school. Unlike the typical American high school senior’s academic calendar that has applications in the fall and AP exams in the spring, the college application season lined up perfectly to clash with my final exams, worth 50% of my grade. Please don’t ask me how I survived — I don’t know either.

The worst part is that after all of this strife, my application may well be dead on arrival simply because I applied for financial aid. Most top American universities are need-blind for domestic applicants, which means that they do not consider an applicant’s ability to pay for the price of their education in their admissions process. This is contrasted against need-aware admission, in which the ability to pay is factored into the decision. Research shows that need-blind admission increases the acceptance rate for students who receive financial aid. However, there are currently only seven institutions that are need-blind and meet the full financial need of international students: Amherst College, Bowdoin College, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Princeton University and Yale University. While I acquiesce that need-blind policy strains financial aid resources, it is disheartening that Vanderbilt — as the institution with the 17th highest endowment and 19th best financial aid nationwide — still practices need-aware admission for international students without any plans to change in the near future. Across the US, this need-aware status makes it much more difficult to access affordable, top-quality education. In other words, if you cannot pay full price, your dream school is just that — a dream.

In 2022, the Common App reported that the proportion of students applying to more than ten institutions has doubled between the 2014-15 and 2021-22 application cycles, and international students applied to nearly two times as many institutions compared to their domestic peers. The report also found that most of these international student applications go to selective private institutions like Vanderbilt, which explains the higher application volume; as acceptance rates at top universities continue to dwindle into single-digit territory, applying to more universities becomes a strategy for international students to increase their chances of admission into at least one institution. For example, I applied to 11 U.S. universities, and Vanderbilt was my only acceptance.

Additionally, while international students may be eligible for Common App fee waivers, they do not qualify for the College Scholarship Service (CSS) profile fee waiver. Most universities require the CSS profile as part of the financial aid application, but it is not free to fill out. Some institutions do provide CSS profile waivers, but most of them do not — Vanderbilt, despite its claims of equal opportunity, falls into the latter category. The CSS profile costs $25 for the first institution and $16 for each additional one. At these rates, if a typical international student applies to 15 schools, that application would cost them a whopping $249.

This is the irony of financial aid — you need aid, but you must be rich enough to apply for that aid. The costs don’t stop there. If accepted, international students are also required to pay for their student visa, which currently costs $510 for undergraduates. While I was privileged enough to be able to afford these costs, they all present real barriers that prevent a lot of talented international students from even applying to U.S. colleges.

Just because I’m here now doesn’t mean the battle is over. I’ve known that I wanted to study in the U.S. since I was 13, but the complete autonomy that comes with being halfway across the world from everyone I’ve ever known and loved got scary really quickly. Like most international students, I committed to attending this school without ever seeing it first. Home might be a few hours away for my American friends; for me, it would be a 30-hour, $1,500 flight. I watch my friends talk about their excitement to be home for Thanksgiving and Christmas, knowing that I will instead be spending my break making the 20-minute trek from my residence hall to Kissam across an almost deserted campus. Campus life is rewarding, but I wish I had the option of going home.

Vanderbilt, if you truly consider international students like me an integral part of this community, it is time you prove it. Extend need-blind admission to all students. Vanderbilt has approximately $700,000 in endowment per student to Brown’s $590,000 — yet Brown is slated to become the eighth need-blind school for international students beginning with the class of 2029. Money is not an excuse not to institute need-blind admission for all applicants. Each applicant should be evaluated on the basis of their personal merit, not by their financial background. Offer the CSS profile fee waiver. Providing this waiver is the only practical way of making the financial aid application accessible to all students.

All this isn’t to say Vanderbilt is horrible. There’s a reason I willingly fought to get here; beyond the amazing people I’ve met, the International Student and Scholar Services and the international community here have been incredible pillars of support. However, if Vanderbilt is truly dedicated to its pledge towards greater equity of opportunity and access, please stop making international students like me feel like naive aliens for daring to dream of being a ‘Dore.