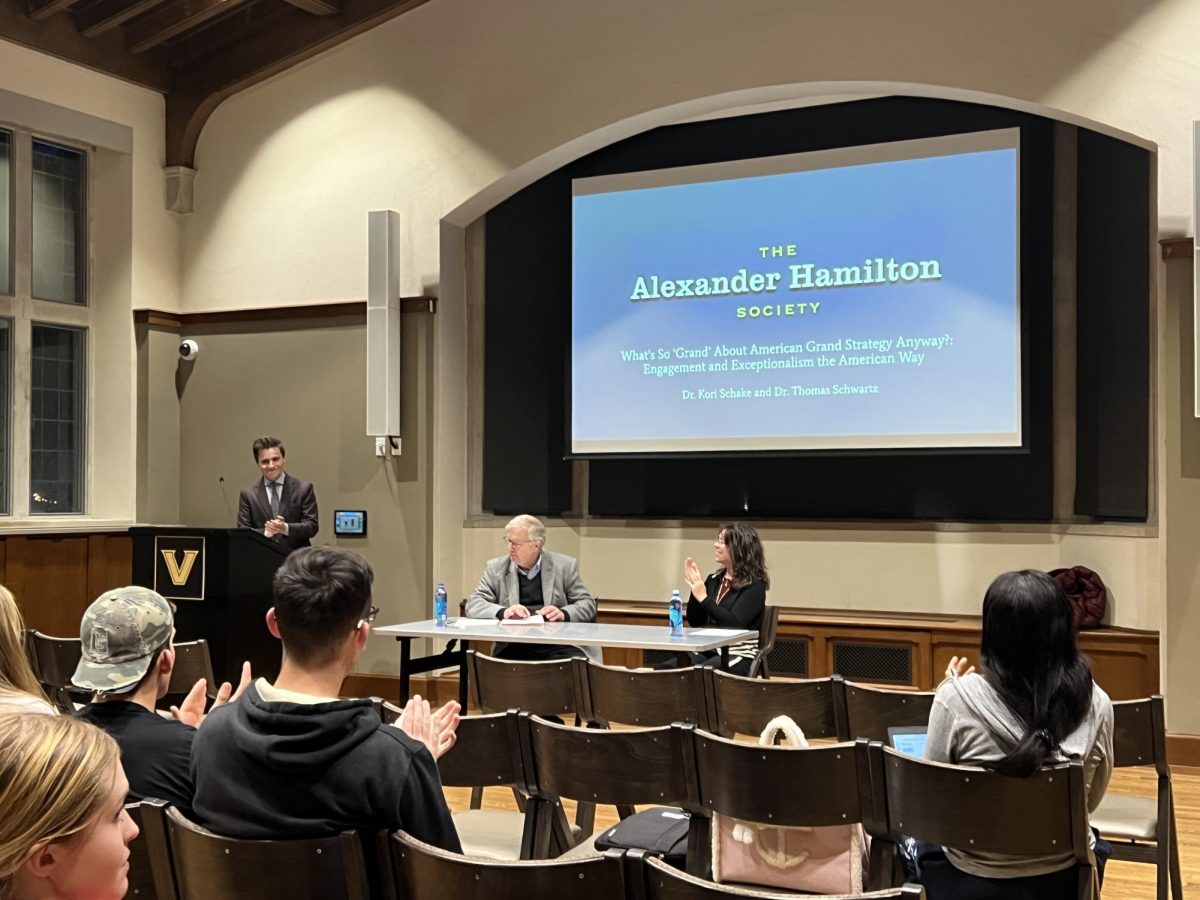

Kori Schake, senior fellow and the director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, spoke to Vanderbilt students and faculty on Nov. 13 about the expectations and realities of America’s presence on the global stage. The event was hosted in Alumni Hall by Vanderbilt’s chapter of the Alexander Hamilton Society.

Prior to joining the AEI, Schake was the Deputy Director General of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London. Schake also served in leadership positions at government agencies including the U.S. Department of State and U.S. Department of Defense. Schake has authored five books and taught at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, College Park.

Schake’s talk on Monday was moderated by Thomas Schwartz, distinguished professor of history, political science and European studies. Schwartz’s most recent book, “Henry Kissinger and American Power: A Political Biography,” examines U.S. engagement in global politics under former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

American grand strategy and exceptionalism

Opening the conversation, Schake defined American grand strategy as outlining the rudimentary principles of American foreign policy.

“It’s the big basics,” Schake said. “It’s your theory of how you think the world works, and how the United States should try and protect it to make ourselves prosperous and safe.”

Schake argued that American grand strategy has existed since the nation’s conception, citing the French Revolution as an early example of U.S. foreign involvement in alignment with grand strategy. Schwartz disagreed with that assertion, calling to attention the evolution that U.S. foreign policy has since undergone as a result of shifting domestic interests.

“The domestic character of the United States shapes foreign policy and political culture,” Schwartz said. “The only thing I would challenge you on is that I think that domestic political culture undergoes changes. It also is a very contested concept of national interest.”

The pair then discussed American exceptionalism — the idea that the U.S. is exemplary compared to other nations — and its connection to both foreign policy and grand strategy.

“I have a viscerally negative reaction to the term ‘American exceptionalism’ because it seems like the last readout of political idiocy,” Schake said. “But, there are unique elements about American policy.”

Schake said the two shaping characteristics of the U.S. are race and space.

“Governing over this much diversity is always a struggle,” Schake said. “The physical expanse of the country gives us different dimensionality and a different perspective on a whole lot of problems.”

Israel and Palestine

Schwartz steered the conversation toward the Middle East and current tensions domestic and abroad about the ongoing conflict. Schake said it would be ideal if the U.S. was not involved in the Middle East.

“The Trump administration, for all the craziness and chaos, actually had the right idea, which is if you can bring Israel and the countries of the Gulf into recognition and deep cooperation with each other, they will have the strength to protect themselves against Iran, and we won’t have to do it,” Schake said.

However, Schake said in the middle of an active war, such a strategy would not be possible. She emphasized that a two-state solution is also highly unlikely.

“It’s hard for me to see how a two-state solution would be possible if Hamas governs Gaza,” Schake said. “And it’s hard for me to see how anybody will have legitimacy running in to govern Gaza.”

Referencing Iran’s involvement in the conflict in Gaza via its funding and support for Hamas and Hezbollah, Schwartz asked Schake whether she would support regime change in Iran.

“I think we should absolutely be in favor of regime change and trying to support civil society groups in Iran,” Schake said. “But, I don’t think we should overthrow Iran’s government because that is a big job, my friends. I don’t even think that the last three presidents would actually carry out what our stated policy is, which is, if Iran doesn’t negotiate an end to its nuclear weapons programs, we will destroy them.”

Russia and Ukraine

Schwartz shifted the conversation towards the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine. Referencing declining public support for American aid to Ukraine, Schwartz asked Schake whether America should have vested national interest in Ukraine — a country that Schwartz stated is not a formal ally of the United States.

Schake raised two arguments in support of continuing U.S. aid to Ukraine.

“The central argument is that for 5% of the American defense budget last year, and zero American deaths, Ukraine is destroying Russia,” Schake said. “That’s going to make us safer, it’s going to make our allies safer and it’s going to make Ukraine safe. And, the second argument is actually it’s always in our interest to try and help people fighting for their freedom.”

Schwartz called attention to allegations of corruption and war-profiteering in Ukraine’s government and whether that should hinder U.S. aid to the state. Schake said that while there is “unquestionably” corruption in Ukraine, the U.S. still has a responsibility to defend the state’s freedom and autonomy.

China and Taiwan

Building off of the idea of freedom-fighting, Schwartz posed the question of whether Schake anticipates China attacking Taiwan in the near future. Schake said she views President Xi Jinping as a “genuine threat” to Taiwan’s liberty but cautions against asserting that the two regions will inevitably go to war.

“Our challenge is less figuring out whether it’s worth fighting than setting them up to be successful,” Schake said. “The more confidence they have that we and others will help them, especially in advance of China attacking Taiwan, it will help make them strong — and that’s the best way to approach the problem.”

Faculty and student interest in U.S. foreign policy

Vanderbilt political science professor Katherine Carroll attended Schake’s foreign policy discussion and offered her own reflections on American grand strategy in terms of building freedom and democracy in regions such as the Middle East.

“I think here we have to say that we advance freedom and democracy in the region provided there is a way to protect American interests while doing so and provided advancing freedom and democracy is fairly easy,” Carroll said.

Carroll added that the real work behind promoting democracy is not as glamorous and much more difficult than it may seem.

“It’s training judges, helping develop curricula in universities, advising political parties, visiting prisons to push for reforms, training civil society organizations and supporting independent journalists in other countries,” Carroll said. “These are long-term, slow, but critical fights in my view. We certainly do some of this, but not enough.”

Carroll said she enjoyed Schake’s talk and believes that students interested in foreign policy benefited from the conversation.

“Kori Schake and I have a long list of common interests, a big one being the U.S. military,” Carroll said. “So for me, her noting that American civil military relations are healthy was the most important part of the presentation. I also think that she, in particular, brought something important to the conversation that I believe students are having with themselves as they consider careers in foreign policy.”

Schake advised students interested in foreign policy to study economics, figure out early on what parts of the world interest them and find people to invest in them.

“If you don’t like [what you do], you’re gonna get trapped into doing it because you’re going to be good at it,” Schake said. “So pick something you like.”

Junior Zacarias Negron, president of the Vanderbilt chapter of the Alexander Hamilton Society, coordinated Monday’s event. Negron, a political science major, said he hopes that Schake’s talk encouraged students to converse more on foreign policy issues.

“I think the reality is that foreign policy surrounds everything we do from the phone calls you make and food we eat and the very lives that we cherish around the world,” Negron said. “I think too few people are having conversations on foreign policy. We’re a big school when it comes to STEM and all kinds of things, but we are super removed from foreign policy.”