CORRECTION: This article was corrected on Nov. 13 at 3:15 p.m. CST. It previously stated that the Women’s Center did not have the resources to host Tarana Burke in spring 2023; however, it was Vanderbilt Student Government that lacked those resources. The Women’s Center did not attempt to bring Burke to campus until this fall.

Tarana Burke, founder of the Me Too movement against sexual harassment, spoke at the annual Margaret Cuninggim Lecture on Nov. 8 in Wilson Hall. The lecture series began in 1988 and occurs each November in honor of the Women’s Center’s founding.

Burke was involved in extensive nonprofit work prior to the Me Too movement, including a mentorship program for young girls affected by sexual violence. Burke began using the phrase “Me Too” in 2006 to encourage conversation around sexual harassment in society.

In 2017, #MeToo went viral on Twitter in the wake of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse allegations. Burke was then named TIME Magazine’s 2017 Person of the Year and earned the 2018 Ridenhour Courage Prize.

“I think I speak for everyone at the event when I say that Tarana Burke’s energy and wisdom appealed to every person in the room,” sophomore Abigail Kwon, a sex education intern with the Women’s Center, said.

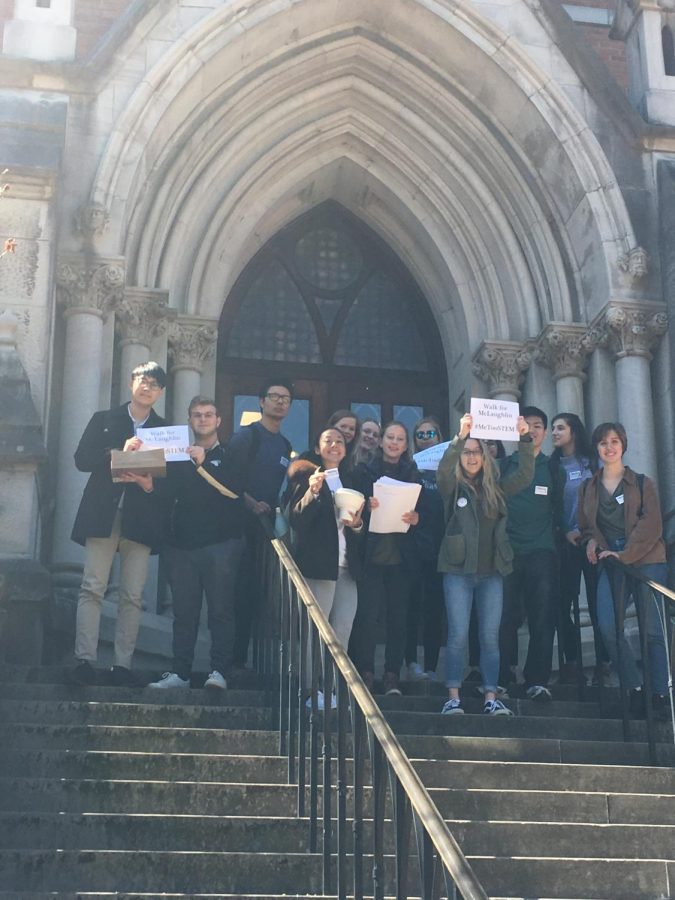

VSG’s Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Committee originally wanted Burke to speak on campus during Sexual Assault Awareness Month in April 2023. While VSG did not have the resources to host her at the time, Women’s Center Director Dr. Rory Dicker was interested in inviting Burke to the lecture series, particularly because many students are familiar with the Me Too movement.

“We try to select someone who might not be invited by an academic department but whose ideas are relevant, inspiring and thought-provoking,” Dicker said. “We thought Tarana Burke would be a perfect speaker for the Cuninggim Lecture, and we were able to partner with VSG, as well as with Student Affairs, Project Safe and Residential Colleges to make this event a reality.”

Burke began the conversation by detailing her inspiration to start the movement and her desire to make a large-scale impact, even before she anticipated Me Too going viral.

“When I was working with girls in a public school in Alabama…a seventh-grade girl would describe an experience that she knew was violence, but that she did not have the language to describe,” Burke said. “That’s when I knew it had to become a movement; in my heart of hearts, I knew it had to be deeper than me.”

Burke then elaborated on the complexities of the movement going viral and her initial reaction to the global response that emerged years after she founded Me Too.

“I think there are big pros and cons,” Burke said. “I don’t think there’s a thing that I could have done as an individual to make the work that I was doing spread across the globe in the way that it has. I was begging people to listen, but the frustrating thing is that myself and tons of colleagues had been trying to bring that kind of attention to the movement for a long time.”

Burke also discussed the drawbacks of the movement garnering media attention and how the narrative around Me Too could sometimes be misconstrued.

“The media will always find a reason to pit women against each other for everything, especially once they get control of the coverage,” Burke said. “We’re here, always, because of the patriarchy. But patriarchy has a hold on the major media, and when the story broke out, there was a lot of focus on the men involved, like R. Kelly and Matt Lauer. People always forget about the survivors involved in the story; sometimes, people can’t even name the women involved.”

After detailing her general reaction to the media attention, Burke discussed the nuances of intersectionality within the movement and the response generated by the Black community.

“When people found out that a Black woman started the movement, all of a sudden, the tide changed,” Burke said. “All of a sudden, it was about Black power, and Black women in particular really came out and supported me because they didn’t want to see another one of us not get credit for our work.”

Burke also described how the media treated her once she was revealed as the founder of the movement.

“Despite the support, there were a lot of times when the media tried hard not to make me the forefront of the movement; they wanted to focus on the Hollywood actresses who were also involved,” Burke said. “Things changed when the TIMES put me on the cover; I became ‘the person’ of the movement just like that. Even then, though, Black women did not get the media attention they deserved within the movement.”

Burke closed the lecture with an audience Q&A, during which she highlighted the importance of continuing to advocate against sexual violence and for a cultural shift in the ways in which survivors are perceived by society.

“The onus is on us now, because the reality of sexual violence in our communities is drastic: it is an epidemic,” Burke said. “Movements are built on people, so we need you to decide that you are a part of the Me Too movement. You can start by having conversations on campus or in your other communities. Just that alone will help others understand that this is not about a hashtag, this is about humanity.”

Senior Tayo Fasan, a Women’s Center ambassador, co-moderated the talk. Fasan said they were impressed with Burke’s multifaceted conversation regarding sexual violence and said the lecture emphasized the prevalence of sexual assault.

“My main takeaway is that sexual violence is one of the greatest public health crises we are facing on this campus, in this country and around the world,” Fasan said. “We have to integrate a deep political and social analysis of sexual violence…if all of us are going to be free.”

Anon VU Staff • Nov 15, 2023 at 10:24 am CST

This talk was absolutely incredible. I really, really loved when she talked about how in addressing the violence and oppression of minority populations that are more often affected, you’re truly helping women of all groups, even white women. It’s all connected. SO enlightening.