A few weeks into my first year at Vanderbilt, I was looking for clubs to join. I had been a member of student council every year since the fifth grade and wanted to join a similar organization in college — somewhere I could get a leadership position early on and make an impact in my community.

In my search for a leadership role, I attended an information session about becoming an officer of my Commons House, Hank Ingram House. In this role, I served on the House Programming Advisory Committee (HPAC) with the other Hank House officers as well as the larger Commons Leadership Council (CLC) with all the officers across the 10 Commons Houses. The main responsibilities of this position included leading our houses in the Commons Cup and planning weekly events for our residents to connect.

After that meeting, I was still on the fence about whether to join HPAC. The main draw for me — aside from the title — was the ability to lead my house in the Commons Cup since I had missed out on a similar spirit competition experience due to the majority of my high school senior year being virtual. This opportunity on its own was not enough to convince me to run, so I decided to let the deadline pass without applying. I only changed my mind after the deadline was extended twice due to a lack of candidates — how could I pass up an opportunity to receive a vice presidential title without having to compete for it?

When I started my new position, that initial excitement faded quickly. What I thought would be a post of great influence turned out to be a spot on a glorified party-planning committee. Similar to organizations like VUcept, we had almost no autonomy in what we were able to do since HPAC is organized under and tightly controlled by Residential Colleges in conjunction with the Dean of Commons. In planning our weekly events, we were only able to make requests and hope they’d be approved. Then every Wednesday night, some food or supplies would arrive — often not what we had ordered — and we’d spend our event in the Hank lobby distributing whatever we’d been given to residents.

I was particularly looking forward to leading Hank in the Commons Cup in hopes of finally getting closure for what I missed in high school. However, I began to dread participating. Instead of thanking us for volunteering our time to rally our houses and build a stronger Commons community, at meetings after Commons Cup events DoC staff lectured us about good sportsmanship and ridiculed us for our houses’ behavior at the events. The Commons Cup was supposed to be an optional activity for us to bond with our houses, but my position on HPAC turned it into a mandatory obligation where I would get nervous if my housemates cheered too loudly.

I don’t want to disparage every aspect of this experience. There were good moments and I’m grateful for many of the relationships I forged with my faculty head of house and other HPAC members. Had it not been for these relationships, I would have quit well before the end of my term.

I’m now a junior, but I still return every once in a while to visit Hank and for a chance to finally experience the signature event as a participant this time — without the stress of running the event. During my most recent visit, I met the current vice president, and she asked me about what I felt I had gained from my time in the role.

My mind was blank.

I’ve spent more time than I’d like to admit being angry about what this position cost me — time, energy and ironically, the first-year experience I was providing for everyone else. It wasn’t until I faced the question of what I gained that I really understood why this position caused me so much strife.

I couldn’t answer this question because the most valuable part of the role was its spot on my resume. I joined because I wanted the title, and — in spite of everything I feel it cost me — I got exactly what I signed up for.

I prioritized stature over substance, and it left me not only unfulfilled, but damaged by the experience. Unfortunately, I’m not alone in this experience. I see Vanderbilt’s obsession with prestige and reputation poisoning the community and corroding the things that actually matter — in many cases, stakes much higher than a weekly first-year event.

At Vanderbilt, we have over 500 student organizations, each with a minimum of four officers; however, many have more. Some organizations — like Vanderbilt Student Government, VUcept and the Commons Leadership Council — are composed entirely of “student leaders.” The result is thousands of leadership positions on a campus with only 7,000 undergraduate students.

There are at least 2,000 leadership positions at Vanderbilt since there are 500 student organizations that each have at least four officers. Those leadership positions reopen each year, so during a Vanderbilt student’s four-year college career, they’ll have over 8,000 leadership opportunities. Vanderbilt only has about 7,000 undergraduate students, meaning there are more leadership opportunities at Vanderbilt than there are students. On average, each Vanderbilt student must spend over one year in some leadership role just to keep every club at Vanderbilt operational.

When there are this many leadership positions available, many of them have little to no responsibilities which diminishes the reputation of those positions that do require hard work and dedication. There is a major difference between a role that requires hours of work each week and a role that just checks a box to fill a spot. Unfortunately, the flooded leadership market has made it hard to decipher what is a real leadership position and what is just a title.

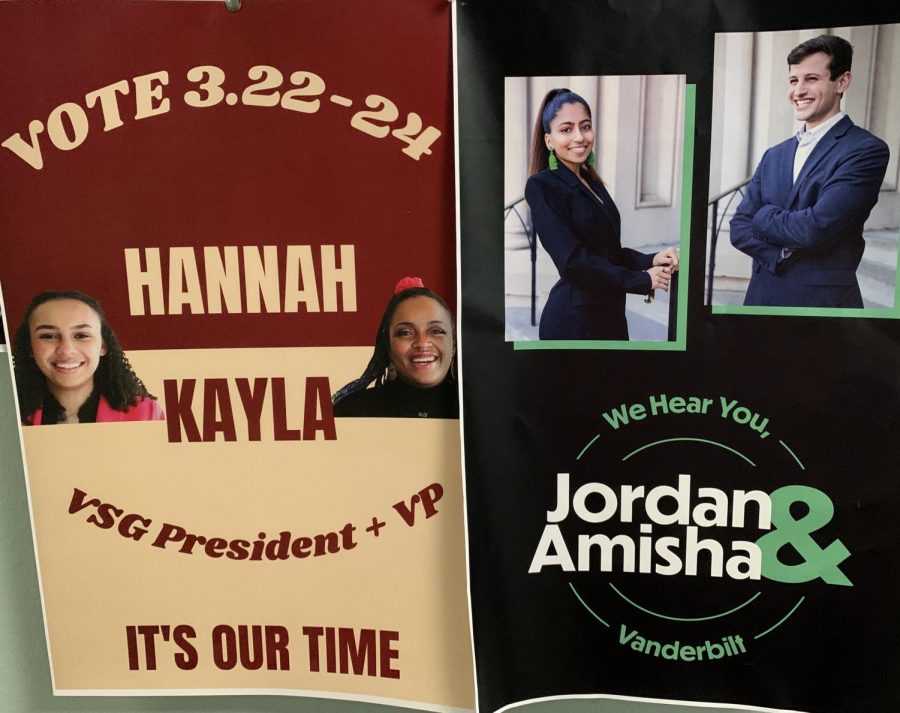

There is no better example of a club that devalued itself to the brink of collapse through an obsession with prestige than Vanderbilt Student Government. VSG is composed of an executive board, a cabinet, a senate, almost a dozen committees and even a judiciary. Every single post counts as some form of leadership on their members’ resumes, but in the process of bolstering themselves with these titles, VSG lost touch with their primary purpose: representing the student body.

Instead of focusing on supporting students, VSG clearly focused on their own members, spending 32% of their budget on themselves. These expenses included $10,000 on bucket hats and hoodies for members.

VSG has created so many leadership positions that it has become bloated, yet they consistently struggle to fill all of their posts. VSG has lost legitimacy as the student body takes them less and less seriously every year. Last year, VSG became such a mockery that the student body fittingly elected satirical candidates to dissolve the body and — as their new president has described in an email to the student body — their “ineffective, confusing, resume-padding antics.”

This problem of outsized emphasis being placed on reputation runs much deeper than Vanderbilt’s clubs. It has become deeply embedded in our community culture.

Most recently, we’ve seen this obsession with prestige play out in Vanderbilt’s recent fall from 13th to 18th in the U.S. News Rankings. Vanderbilt fell five spots in an arbitrary list and both administrators and students freaked out. This reaction was driven only by concern towards perception — the university listed at the top of their resumes just got five points worse. The quality of Vanderbilt’s education was no worse the day after the new rankings were released, but panic ensued nonetheless.

Administrators went right to work trying to challenge the methodology that robbed the university of five whole spots in the ranking. Through their multiple emails attacking the methodology, the administration gave so much attention towards the rankings, they inadvertently served to legitimize them.

It can often feel that our leaders are obsessed with their rankings and prestige instead of making meaningful change. Despite the outrage over the drop in rankings, I have yet to hear about any plans to improve the educational experience Vanderbilt provides like expanding class offerings. Their focus isn’t making substantive improvements to the school itself; it’s about making Vanderbilt look prestigious by changing one set of arbitrary criteria into a different set of more favorable — but still just as arbitrary — criteria. Whether it’s students trying to bolster themselves with arbitrary titles or the Vanderbilt administration lobbying to change a news outlet’s ranking methodology, this obsession with resumes and reputation seeps through every level of Vanderbilt.

While I would like to say that we should just ignore our resumes and image, that’s just not practical. There are times when it’s important to show off our accomplishments, and we need to have an impressive resume put together in order to do that.

What I’m suggesting is that we flip our priorities. Instead of doing things to fill our resumes, we fill our resumes with the things we do. If we join and build organizations we believe in, they will speak for themselves and provide us a much more genuine item for our list of accomplishments.

Each of us has different interests and goals. HPAC was a bad fit for me because I cared more about the title than the job description, but it might be a better fit for someone truly interested in those responsibilities. There is no organization or position that is automatically a resume padder, but rather our intentions set the tone. The best way to fight back against a culture that prioritizes reputation and prestige over substance is to question your own motives.

Why did you join that club? Why are you in your major? Why did you choose Vanderbilt?

If you find those motives are misguided, leave the titles behind and prioritize what is truly important.