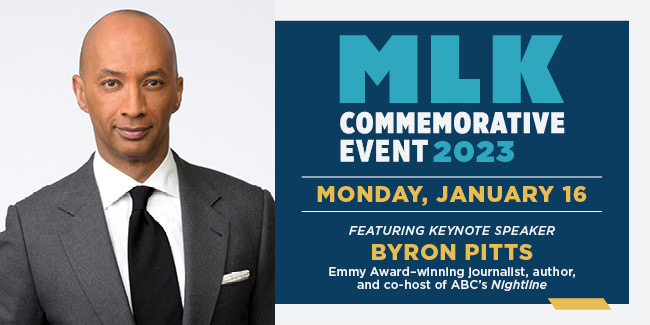

Journalist and author Byron Pitts was the keynote speaker of Vanderbilt’s 2023 Martin Luther King Jr. Day Commemorative Event on Jan. 16. This year’s theme was about “Cultivating a Beloved Community Mindset to Transform Unjust Systems.”

Each year, the university hosts a lineup of events to celebrate MLK’s legacy. In addition to the speaker event, this year the university held a blood drive, a joint day of service at Meharry Medical College and a march and convocation in Downtown Nashville.

Pitts is the co-anchor of ABC’s “Nightline” and was formerly a “60 Minutes” correspondent and the chief national correspondent of “The CBS Evening News.” He won an Emmy for his coverage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and has reported on wars and other events around the globe, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the fall of the Saddam Hussein statue, the Boston Marathon bombing and more. Pitts is also the author of “Step Out on Nothing: How Faith and Family Helped Me Conquer Life’s Challenges,” which chronicles his childhood hardships and his family’s sacrifices that made his journey possible.

During the speaker event, Pitts spoke about the opportunity that comes with attending college, especially a university of Vanderbilt’s caliber. He encouraged students and other guests to use their talents and educational privilege to help those who are less fortunate and to show gratitude. Pitts gave the example of how many counties around the country, including one in Tennessee, have fewer dining facilities than Vanderbilt’s 18.

“You are living someone else’s dream,” Pitts said.

As a first-generation college student who learned to read at age 13 and grew up in poverty, Pitts described how faith and family have motivated him through hardship. These motivators and his “optimism by choice” mindset also directed him in his career, particularly when he was faced with workplace discrimination. Growing up in the Civil Rights Movement, he spoke about the modern-day significance of MLK and other Civil Rights giants’ work.

Prior to the keynote event, which was available virtually and in-person, The Hustler spoke with Pitts about his life and career, as well as MLK’s legacy.

The Hustler: What were some of the most impactful stories that you’ve reported on in your career?

Byron Pitts: In no particular order: I covered 9/11 when I was lead correspondent for CBS. That was impactful because, professionally, it’s where I first made my bones as a network correspondent covering such a major story. I got to see human beings at their best and at their worst. It was one of the handful of times in my professional life where I’ve seen people die. That was impactful. It changed our country. I think the innocence that Americans may have enjoyed left after that. We experienced a lot. We experienced terrorism while many parts of the world had experienced it already.

Covering the war in Afghanistan was also impactful. Watching many American service members give their lives for our country. Our group interviewed Nelson Mandela as a young reporter. Some of my favorite interviews professionally other than Mandela was John Lewis, who was educated here in Nashville. Wonderful man. And like every dynamic person I’ve ever interviewed, male or female, they have common traits. Oftentimes, there’s a level of humility to them. There is a toughness that’s undeniable that you see in their eyes and how they carry themselves.

You talked about your connection and participation to the civil rights movement. From that, what principles do you think Vanderbilt students can embrace today and all year that MLK and other figures at that time really advocated for?

I think that all of us have the opportunity and a responsibility to serve. The Bible says ‘to those who much is given, much is required.’ Vanderbilt has some of the brightest students in all the world; it’s one of the finest institutions in all the world. So I think this is a space where excellence is around you, and students should embrace the responsibility. How can you serve? Not just how much money you can make or how successful you can be. I would argue, the more successful you are, the more famous and wealthier you are. Booker T. Washington once said, ‘place a bucket where you stand.’ And I love that. To me, what that says whether you are an old man like me, or a college student, freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, grad student: how can you serve, right where you are, right now in what you’re doing? My grandmother would always say that the only way God can give you more is if you open your arms and share what you have. And life has taught me that there is nothing more rewarding than serving other people. I think in many ways, I think being of service is a selfish act, because you get so much from serving.

Throughout your life, you’ve also experienced hardship yourself. Have you also experienced professional challenges and, if so, what were the most unexpected ones?

In my 42 years as a journalist, I’ve gotten jobs because I was Black. I’ve been denied jobs because I was Black. Oftentimes, race and gender can be a double-edged sword for sure. At a job in local television early in my career, my boss at the time was also a friend of mine. When I was applying to be an anchor there, he said ‘I gotta tell you something, and I’m sure it will upset you, but you can either let it eat you, you can stay here and be angry, you can leave and be angry or you can leave for the next better opportunity.’ He told me that the owner of the station at the time said in a meeting ‘as long as I run this station, a nigger will never anchor it.’ This was like 1988; it’s not all that long ago, and I was crushed by it. It was the first time I’d ever felt a full frontal attack of racism in my professional life, even though I presumed it existed. And my boss, who was white, was incredibly kind and supportive. He said, ‘if you want to sue, if I’m called to testify, I’ll testify to what I was told. But, for the most part, you’ll be blackballed in this business. If you want to leave early, I’ll let you out of your contract. And I’ll give you the best recommendation. And I’ll always be your friend.’ I was upset for a few days, but took his advice. I got out of my contract early and went on with my career. But this experience ended up being a powerful lesson. All of us will face obstacles. Black, white, male, female, gay, straight, white — wherever you are on the spectrum. And it’s what you do with it. Do you allow it to be the worst day in your life? Or do you allow it to destroy your life?

I can only imagine how difficult it was to experience prejudice in the face of your dream. And I can also imagine, on the flip side, that finally achieving that dream was that much more meaningful. How has it lived up to your expectations? What advice would you give to aspiring journalists and other young people who are chasing their dream jobs, and maybe facing hardship?

Back when I was 18 years old, dreaming of network correspondence seemed like an unreasonable dream. I was on academic probation, my girlfriend just dumped me. But, I eventually achieved it. I encourage people to dream bigger; however big your dream is now, make it twice as big; make it 10 times larger. The pastor of the church I grew up in Baltimore had a great saying. He says if you reach for the stars, you’ll fall on the moon. My interpretation of this saying is that your dream should be bold, outrageous and way out there. And let’s say for whatever reason, you don’t necessarily get to it. You’ll get to something equally, if not more remarkable. Sometimes I’d even dream bigger.

You described how there’s so much more that you can dream of and so many students across the country are dreaming of exactly what you are doing now. What do you think that the role of journalism and other types of media are today in civil rights and other activist movements?

I think the responsibility of journalists is the same today as it was at the beginning of our nation’s beginning. Speak truth to power, afflict the comfortable, comfort the afflicted, shed light in dark places, give voice to the voiceless. If you can do that in a day or, in my case, 40+ years, that’s a good day; that’s a good career.

As a journalist, I don’t think my opinion should matter. I think my personal life experience should impact how I see the world and how I cover events, but it shouldn’t shape the truth, right? I’m a 62-year-old Black man, raised in inner-city Baltimore. So my life experience allowed me to see law enforcement in one life. My life experience allowed me to see poverty in one life. I had a handful of friends growing up who were street pharmaceutical salesmen, and these are guys who I respected. Some made bad choices. Others thought they didn’t have any other choice but to make them. While all those experiences color how I see the world, my job as a journalist is still to go where the facts and the truth lead me.

I remember an experience earlier in my career just out of college. I was covering a Klu Klux Klan Jamboree in North Carolina. I got the assignment early in my career. I wouldn’t say no to any assignment. My rule was never say no, and when they say come home, ask to stay longer. That was my mantra for a long time in my career. So I went to this Klan rally, and they invited me to spend the night. We’re in the middle of nowhere in North Carolina. And I wake up the next morning to the sound of a children’s choir singing Amazing Grace, which is a fundamental song in the Christian faith. What was interesting is it has its own connection to slavery which I’m sure these people weren’t aware of. And so I opened up the tent I was sleeping in, startled because I recognized the song from my life experience of having grown up in church. There was a choir full of young people probably 12-20 years old, in their Klan robes, the Klan robes, some with their hoods on. It was such a powerful moment for me. Certainly, as a person of faith, I have my own relationship with the song. As a Black person, I have my own opinions about the Ku Klux Klan. But that moment reminded me that I wasn’t there necessarily as a Christian. I wasn’t there necessarily as a Black man. I was there as a journalist. And my job was to be respectful of them, to hear what they had to say, to honor their truth or to show what truth existed. It isn’t about how I think they may see me or how they see people who look like me. Certainly, I have my own life experience that I brought to that conversation, but it’s not about me.

So that experience was at the beginning of your career. Did you create boundaries for yourself in terms of what you wanted to cover and how you wanted to cover it as you progressed in your career? Or are you still all in all the time?

I’m still all in, but I prefer stories about the human struggle. I’m less interested in stories about sports figures and celebrities. You know, I cover politics as a necessary evil in my business. But I like stories about people who are struggling to figure it out because we’re all struggling. Everybody’s having a hard time and to get the opportunity to be with people when they’re having a difficult moment, they respond. I find incredibly interesting and rewarding work to do. So those are the stories that most appealed to me.

I feel like, as humans, we have more in common, and I authentically believe that humans are good, but that we do bad things. I authentically believe that everyone is deserving of grace. I authentically believe that hurt people hurt people. That is true of almost every story of violence that I’ve ever covered. The person who was the accused or the convicted perpetrator had been hurt at some point in their lifetime. That doesn’t justify what they do. And I certainly believe in accountability for all of us. But I have some empathy for them. I covered two executions in my career. One was lethal injection of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, the other was James Richardson, who was electrocuted in Virginia. In both cases, there were moments in their life where society failed them, where their families failed them. This doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t pay a price for their acts of evil. But I also feel like while we’re staring at them, we should also look at our society and what created that space for them to do so; I’m always mindful of that. I’m always looking for that because all of us are deserving of grace, and none of us want to be judged fully by our worst day. But, oftentimes in my business, that’s when I show up for people — their worst day.

You’ve talked about these jarring experiences that really contrast with your vision of humanity, beliefs and experiences. How do you approach reporting on those instances objectively, while also giving appropriate context?

I’m a paid observer. For instance, 9/11 was one of the most difficult personal days but one of the easiest days of my professional life, because it was all about who, what, when, where and how. Journalism, at its base point, is pretty simple. It’s not that complicated. And so it’s my job to go document things. It’s my job to hopefully get context to events. And that’s a full time job. So I don’t get into giving my opinion.

I work not to take things personally when people come at me for different reasons. I work really hard to be respectful. I have a rule that I won’t shake the hand of certain kinds of criminals. Almost anyone who I’ll talk to, I’ll extend my hand. But I’ve interviewed a couple of serial killers, and I won’t extend my hand. If I’m talking to someone who the evidence would suggest they’re immoral and unethical, I won’t shake their hand.

This piece has been edited for length and clarity.