With an afternoon headache sinking in and my sweaty legs sticking together, I seethed, alone, in the back seat of our rental car. My parents—mom in front, dad trailing behind—were making their way to look at the waterfall for a third time that day, albeit from a different view. After a few deep breaths, I summoned the will to push my exhaustion aside and get out of the car. We had braved the throngs of tourists all day: the slow couples who stood right in the middle of the boardwalk for a photo, the 30-person family sporting matching t-shirts and the bus-riding tour groups of senior citizens. Walking through yet another rocky corridor plagued with people just to see a waterfall I had already seen twice was not of interest to me, but neither was a tense four-hour drive back to our rental house. We found a place where we could catch a clear view of the Lower Yellowstone River Falls in all its glory: an unbelievable drop of over 300 feet which makes all of the park’s chaos fade into the background.

It’s easy to understand why one of the lookouts onto this waterfall is called Artist’s Point, with its unobstructed views of sloping gold-orange canyons streaked with pine trees and, of course, the falls cascading into the foamy river below. It’s a view worth stopping for, one almost too accessible, too spectacular not to attract massive crowds. At this spot, you don’t even need to hike to reach the view. Just parking and walking a few hundred feet will get you there. Even after many trips to Yellowstone spent navigating crowded boardwalks and sitting in traffic for hours, I somehow expected a peaceful nature-viewing experience. In the Park it’s not difficult to see natural beauty, but experiencing nature, without crowds, is a completely different animal.

*****

I’ve gathered a collection of memories—some are personal, and others are from friends in the area who I’ve interviewed—to piece together a narrative exploring our relationships with nature and how they can be altered by tourism. Do the places we enjoy become fundamentally different as others begin to enjoy them, too? How can we find nature amidst the crowds?

*****

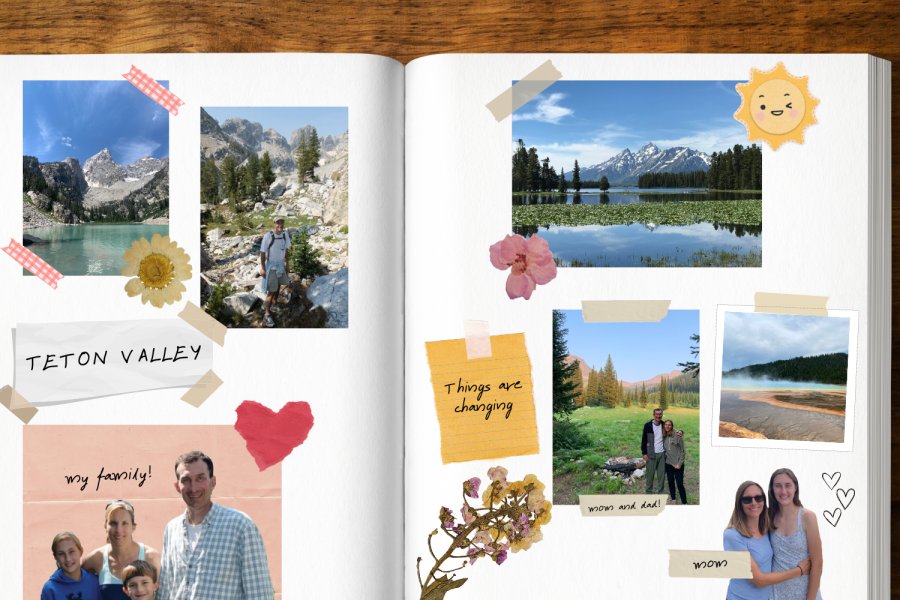

Heather Fisher, my mom’s best friend from college, and her husband Jon began visiting Jackson, Wyoming, when they got married in 1995. They would stay in Heather’s mother’s house: a log cabin-style home up on the hillside at Spring Creek Ranch between the town and the Tetons, complete with cowhide rugs and a porch that looked out over fields which stretched to the mountains beyond. The Fishers brought my parents out there before I was born. One of those times, my parents, Jon and Heather got lost together while backpacking through the Gros Ventre Wilderness. I’ve heard a saga time and time again about when they were stuck in a boulder field during a lightning storm and had to camp there before a group of ranchers came to their rescue. To my parents, this was true wilderness, made even more exciting by the prospect of exploring it with some of their closest friends. Jon always told Heather they’d move out there one day. That day finally arrived in 2008 when he got a job and they sold their house in Tennessee.

The Fishers had their sights set on Jackson Hole, south of Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, on the eastern side of the mountains they knew and loved, but this vision was out of reach. Friends from church introduced them to Victor, Idaho, on the western side of the mountains, an area they set out to explore for a potential new home. Less shiny and crowded, the one-library, one-post-office town was a quieter, more affordable alternative and still close to Jackson. As the Fishers experienced the arrival of spring and then summer, the Valley blossomed: the sun illuminated the golden barley fields under the watchful gaze of the Grand Teton peak and its year-round snow cap. Neighbors stayed outside: barbecuing, walking their dogs and letting their children play near the street. The Fishers finally moved into their house in Victor on the Fourth of July: their own personal Independence Day.

About a century earlier, Victor was just another Western town, one renowned as a hideout for horse thieves and fur trappers in a land long-inhabited by the Shoshone, Bannock and Blackfoot peoples. Teton Valley has become an enclave for the community-oriented nature-seeker, for those like Heather and Jon who always spent time outside even during the winter. Before the town’s incorporation in 1889, the southernmost part of Teton Valley was settled by Mormon families from northern Utah who journeyed by wagon, intrigued by this plentiful, expansive land. The town of Victor was named after a beloved mail carrier, George Victor Sherwood, who delivered the Valley’s mail over the Teton Pass to Jackson Hole on foot. In 1913, Victor was connected by railroad to Driggs, an adjacent town, which opened up new opportunities for the transport of livestock and other goods. The Oregon Short Line railroad united Victor with the greater Teton Basin, known by mountain men as “Pierre’s Hole.”

These days, Highway 33 cuts straight down the Valley and runs parallel to the old railroad tracks which now serve as a walking path between the two towns. If you look to the right while driving from Victor to Driggs, you’ll see my favorite attraction, The Spud: Teton Valley’s premier drive-in movie theater complete with an old pickup truck at the entrance carrying a large, fake potato in the flatbed. The same dusty potato, I believe, sat there 13 years ago when we first visited. When I began traveling here with my family, I would have to explain to friends at school what we were doing in Wyoming and Idaho. I think they pictured forests and potato fields: just a lot of nothing. Now I see little pieces of the area wherever I go–on laptop stickers and t-shirts and in Instagram posts–and people will tell me about their favorite hikes they’ve done near Jackson, or at least that they’ve heard about the area’s beauty.

Since the summer my family arrived, many of the empty fields have been transformed into upscale housing developments, some of which are beginning to extend onto the once-wild mountain foothills. The parking lots for tucked-away hiking trails off the Pass and the backroads of Victor are often full. Now, Teton Valley is on the map for its proximity to hiking and skiing, its popular summer music festival and the Victor Emporium’s famous huckleberry milkshake. Millions of people visit Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks every year. With longer lift lines at resorts, rising home prices and increased traffic, these changes beg the question, is the Valley losing the core of what drew people here in the first place?

*****

The first time I went to Idaho, I laid on the back seat carsick as Heather’s suburban wound around the rounded curves which dropped into steep cliffs before meeting the forest below. The Tetons had revealed themselves earlier in the day, glowing in the afternoon sun on the runway in Jackson Hole as we walked across the tarmac and under the spiny arch of elk antlers at the airport’s entrance. Somehow the mountain peaks were still snowy, even though it was summer. Now, there were no Tetons to be seen through the haze, just an endless snaking road which my nausea would not even permit me to sit up and view out the window. I jumped out of the car once we pulled into Heather’s driveway just before throwing up the can of Lay’s Stax chips I begged my mom to buy me on the flight. It was August, the hottest month in my native New Orleans; here, in the newly mulched landscaping of the Fishers’ yard, my small pile of vomit froze over by the next morning.

The following few weeks were filled with unprecedented joy—the kind you can only experience as a child, or visiting somewhere for the first time, or, ideally, both. Luckily for me, I had plenty of built-in friends to entertain me between the Fishers’ four children, Kathleen, Emily, Jon David and Matthew, as well as their friends and neighbors. We jumped bikes over ramps and rode through empty fields to the dried up neighborhood creek. We watched the summer Olympics and played Wii and listened to audiobooks. We became pioneers in the backyard, making salad out of weeds and dough out of flour to sustain us on our imagined journeys on the Oregon Trail. The grass in the Fishers’ backyard was softer than any grass I’d run through before, and the wind was cool, even in the summer. Best of all, you could see the mountains right through the screen door.

On a hike that first summer, we walked for hours on a dusty, tree-lined trail as the bluest sky stretched wide above us. I ripped my favorite hot pink shorts when I slipped and fell on some rocks near the waterfall at our turnaround point. My mom promised that we would pick out a fun patch in the national park gift shop to iron over the tear.

As we retraced our route—muddy, worn-out little brothers having assumed their positions in our parents’ arms—we would only pass the occasional hiker. It seemed like our backpacks full of sandwiches and oatmeal chocolate chip cookies, coupled with the quiet trails, could attract a wild animal. It felt like wilderness, just the way I’d imagined it: quiet except for the trees rustling and our shoes disrupting the gravel, not a building in sight to break the perfect, clear skyline.

The West was a new kind of paradise, my own semblance of Manifest Destiny completely open for me to explore. It was one in which I had friends to play with but could roam free, where I was allowed to ride a bike without a helmet, where I could be out in quiet nature and maybe even see a chipmunk or, better yet, a moose. I could look at rocks and trees I’d never seen before, and I could pick flowers and lay in the Fishers’ yard without the distractions of noisy traffic and childhood responsibilities. When my parents would take me and my brother to Yellowstone for a few days, I would run out onto the boardwalk to catch a view of the rainbow pools and all of their sulphury bubbles, like something out of a Dr. Seuss book. I had a new favorite corner of nature: one with rivers and mountains and ridges and fields, one with a marvelous quiet and the mystery of a land largely untouched by city.

*****

One summer years ago, the Fishers and my family went camping near Colter Bay, a smaller corner of Jackson Lake and the largest body of water in Grand Teton National Park. I loved the camaraderie of the shared campground space: seeing and hearing families across the fences of trees bordering our own plot and roasting marshmallows at the ashy fire pit over which so many marshmallows had been roasted before. People would walk their dogs and let their kids ride bikes down the looping RV park road as if it were a neighborhood street. We tied a long, knotted rope to a tree so we could climb down the sandy cliff to the pebbly beach below and attempt to skip rocks. We sat in the patterned camper booth to play Spoons together, and Jon played Johnny Cash on the camper’s speakers with the door open so we could hear the music outside. At sunset, we admired the views of the Tetons reflected on the lake, soaking in the last chilly moments before a campfire dinner and a nearly sleepless night in the truck camper on the flatbed of an old, light blue Ford.

The last time we drove through Grand Teton National Park, my parents couldn’t even find the area where we’d camped that year. Now, the highways and parking lots are always crowded with people who have traveled, just as we have, to pull over the car to take pictures and drink in the pure mountain air. I can see the wonder in their eyes because I know it so well: It’s how I felt when I first saw the Tetons, and I get a glimpse of it each time we get off the plane in Jackson Hole and are greeted by them once more. As a child, I felt like my parents, my brother and I were the only ones who saw the mountains and knew them intimately, visited them as if they were family. I felt as if the Tetons belonged to us, and all of a sudden, they don’t anymore.

*****

“Our town went from being a community to being a tourist town.”

I met Diane and Jeff in the summer of 2021 when they led my family on a three-day backpacking trip through the Jedediah Smith Wilderness and down the Teton Crest Trail. They are a couple of self-described “ski bums” who met at Grand Targhee Resort in the ‘90s. They’ve lived in the area ever since, witnessing the changes over 30-something years as professional outfitters and community members. On our trip, Diane made my mom French press coffee in the mornings and helped her get the best pictures of wildflowers. Jeff filtered all of our water and told us about the area’s history and the famous mountain men who once walked the same trails we were hiking. They brought tents, sleep mats and chairs and reheated home-cooked meals for us over a camping stove each night; all we had to do was carry our packs. They provided us with what seemed to be their comprehensive overview of Teton Valley and the surrounding area, peppered with grievances about the flocks of tourists crowding the area and buying up vacation homes. For the majority of the trip, the song “Jack and Diane,” for its eerie similarity to “Jeff and Diane,” was on a loop in my head as I walked down the trail, unable to switch it off. A little ditty ‘bout Jack & Diane/ Two American kids growing up in the heart land…

In Teton Valley, Idaho, it is becoming easier to be a tourist and more difficult to be a local, according to Jeff and Diane. During the busiest times of year, it is nearly impossible to get a table at a restaurant or to make a quick trip to the store. Once the area’s best-kept secret, hiking trails are all part of the public domain now and have lost their awe-inspiring wildness. To ski in untracked powder, get onto the hiking trails when they’re quiet and get into the park when there won’t be a massive traffic jam, locals plan ahead and wake up early. Jeff and Diane have resorted to riding bikes in lieu of driving to avoid the challenge of finding a parking spot. The very tourists to whom they cater with backpacking trips and ski adventures are the ones crowding the stores, national parks and roads, seeking to enjoy the same nature which brought Jeff and Diane to the Tetons decades ago.

*****

As of last year, my family owns a house in Driggs, about 11 miles straight north from the Fishers’ place. Our house is in a Valley where the locals’ ability to enjoy the place they live has waned due to the barrage of visitors seeking nature wherever they can find it. But what makes us different from the locals? After all, we all arrived the same way: Heather and Jon, Jeff and Diane, the tour buses of grandparents. We all took a pilgrimage out West in hopes of a communion with nature—one which would heal us and transform us and bewilder us. We’ve just arrived at different times.

If you watched my dad take a picture of me and my mom in front of the Lower Yellowstone River Falls on our last trip, you wouldn’t be able to distinguish us from any of the other park-goers. In those record visitor numbers to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, you will find me and my family among millions of other tourists, from the loud-talking to the selfie-stick-wielding, only differentiated from everyone else by our lack of need for a park map.

*****

At Taggart Lake in central Grand Teton, the parking lot for the trailhead is nearly always full. At the tail end of our last trip at the very beginning of August 2022—a peak season—we approached the flat, dusty trail which is part of the notoriously tame lake hike. It’s mostly enjoyed by older people, white hair smushed under visors and baseball caps, and young children, often carried back to the parking lot on dads’ shoulders. At one point, we noticed a cluster of people gathered ahead and discovered that someone spotted a moose across the stream. Parents stepped aside so that children could poke their heads through the crowd to see, and the prepared hikers whipped out binoculars to get a better view. The moose stood there, eating grass and minding his own business, despite all the chaos around him. Was he resigned to the fact that tourists had taken over his home, or ignorant or just tired?

Taggart Lake is filled with glass-clear water, revealing a floor of beautifully round stones below. Like Jackson Lake, the Tetons and their surrounding skies reflect onto the surface of Taggart like a perfect mirror image, only cracked by the people wading into the middle for a picture or the child who eagerly jumps into the cold water, unknowingly lucky that his mom thought to pack a towel.

As the lake emerged just past the end of the trail, I was reminded of why my parents brought me there from a young age when I sometimes wished we could go to Disney World instead, like the other kids in my class. The warmth of the high-altitude sun peeked through the canopy of pine branches above. The chatter and laughter and splashing somehow felt natural there, perfectly interwoven with the mountain quiet, yet with each unique thread visible: the talking families sitting in foldable camping chairs, the subtly chirping birds hidden in the greenery, the rippling water as yet another little girl pushed her inner tube into the lake. My parents and I stood in silence, arms crossed, gazing out over the expanse of nature in front of us. Though the crowdedness of the national parks and hiking trails I love had been a point of frustration, it was a redemptive experience to see all these people at peace in nature, the way I had been so many times before. Beyond the lake the mountains glowed in the distance, as if beckoning us all to enjoy the land they call home.