Vanderbilt Ph.D. students: How would you like to make $40,000 a year?

In September, our peers at Duke University received news that their minimum stipends would be raised by 11.4% to approximately $39,000. The catalyst for this change? Nine days before Duke administrators announced the raise, 100 graduate students in Durham organized a simple and peaceful rally for higher wages. These students stood up and firmly asked their administrations to be paid what they deserve — and it worked.

Vandy, this should be our wake-up call.

Ph.D. students are experiencing unprecedented hardship. Inflation is at a record 40-year high, amounting to a 13% decrease in buying power since January 2020. You read that right: one in seven of the dollars that we were promised have been effectively cut from our paychecks, amounting to a $4,000 decrease in our stipend value, assuming a $30,000 stipend from 2020 to 2022. Would you re-sign your offer letter knowing what you know now?

Probably not, especially considering the catastrophic housing market surrounding Vanderbilt. A new study finds that Nashville has the 14th highest income required to afford rent of any city in the United States. The Graduate Student Council has heard heartbreaking stories from so many students about being priced out of their apartments, sacrificing critical medical services in favor of rent and being relocated further and further away from campus to make ends meet. We were disappointed to learn that Vanderbilt’s solution to the housing shortage—a new graduate student housing complex—is charging 50-70% of our stipends for their smallest unit, which provides occupants only 275 square feet of living space. The Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable housing as no more than 30% of one’s income. In addition to housing, the graduate student stipend must cover cost of living expenses such as insurance, car-related expenses, and food. The result: graduate student workers cannot invest in their futures and may even accrue debt during their time spent working at Vanderbilt.

The elephant in the room has grown too large to ignore, and it’s time that we name it: Vanderbilt must raise our stipends to a living wage.

It’s important to acknowledge that, unlike other universities that guarantee all Ph.D. students a certain amount of funding, Vanderbilt’s stipends vary greatly based on program. Even with this range, according to data on department stipends collected from students by Vanderbilt Graduate Workers United, none of our 57 graduate programs paid a Nashville living wage of at least $35,312 in 2022. The highest-paid students, who are in Biomedical Sciences, were paid almost this much but recently wrote an open letter signed by 100 students citing how long hours dilute the value of their stipends and have contributed to a mental health crisis.

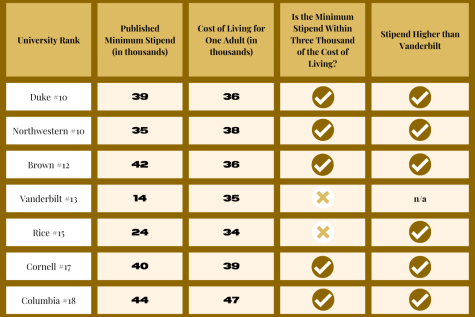

Peer universities across the country have already beaten Vanderbilt to the punch. To demonstrate this, six universities similar in rank and prestige to Vanderbilt were chosen and minimum stipend and cost of living information were collected. Vanderbilt’s minimum Ph.D. stipend is noticeably less attractive when compared to the cost of living in each school’s surrounding area.

Graduate students bring an incalculable amount of value to the university; we are recruited because we are the best and brightest in our disciplines and earn Vanderbilt millions of dollars in funding. Beyond our inherent value, the National Labor Relations Board recognizes salaried graduate students as workers, employees of the university. “Students” is a misnomer that perpetuates the idea that salaried graduate students do not deserve comprehensive medical insurance, a living wage or equal regard to that of their other colleagues at the university.

We have entered a Ph.D. stipend state of emergency, and the time to act is now. Vanderbilt students of all ages should make a commitment to help their peers to earn a livable wage. Fill out the anonymous GSC graduate student life survey and let us know your rent, health and living costs so that our effort can be data-driven rather than anecdotal. Advocate with organizations such as Graduate Workers United and the Organization of Black Graduate and Professional Students that are holding effective demonstrations advocating for improved conditions. Come to our GSC general body meetings every first Thursday of the month to share your feedback about how we can more strategically enact our affordability campaign.

Graduate students are students and should be grateful for what little they get. Or at least that’s what we’ve been made to feel when our concerns have been dismissed or simply unheeded by administrators as we continue to face increasing costs of living, stagnating wages and mental health burnout. Make no mistake, though: When we work together, collect and share data and organize across departments, we too can soon enjoy a future where we invest more into our studies and less into our rent.

The university’s 2022 financial report boasts that “Vanderbilt University is stronger, by every metric, than at any time in our history.” To that we say: Vandy, put your money where your mouth is and invest strongly in your graduate students. Pay us not just a living wage, but at least a $40,000 wage that’s competitive with our peers and transformative for our well-being.

KKona • Nov 14, 2022 at 8:45 pm CST

Just get a real job!!!

God • Nov 16, 2022 at 3:47 pm CST

You first!