Long-distance running is lonely.

Waking up in the early mornings before the sun rises is lonely. Hearing nothing but your own footsteps on the pavement is lonely. The early nights and endless miles are lonely. The muscle pain and calf aches and stiff legs are also lonely. Most of us listen to music or podcasts to pass the time because listening to someone else—hearing another human presence—makes the miles less lonely.

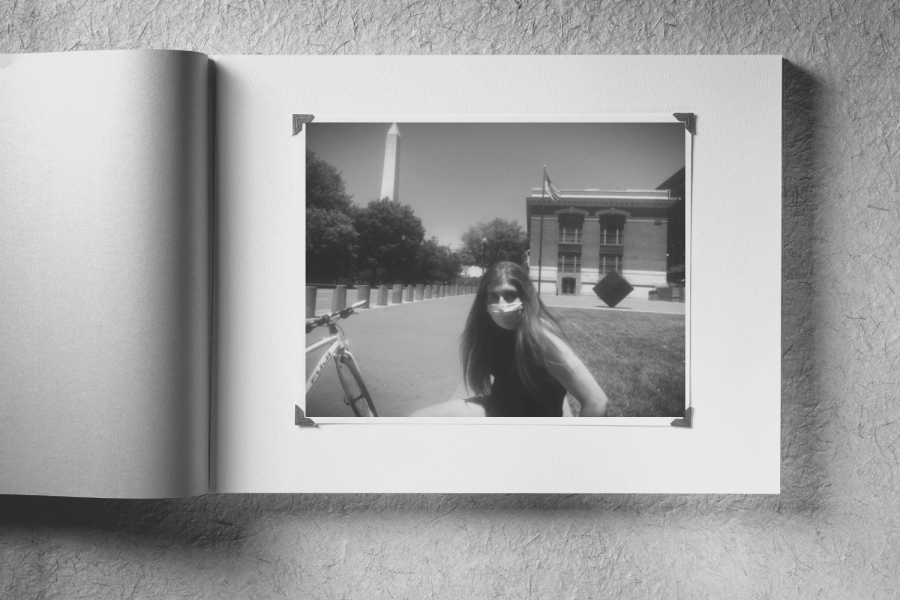

My first year at Vanderbilt felt like a long run. I’m sure I had felt lonely at points before then, but those months were the first time that solitude shaped my days. I walked around the deserted Commons grounds several times a day to escape the monotony of online classes. I hid my face behind a mask, stayed inside and worked hard.

Vanderbilt can be a lonely place. There’s the dull ache of being away from family and trying to build a new life and home from scratch. The social environment is new, isolating and feels transactionary. Friendships are based on proximity and ease and random computer-generated assignments. You’re told that your friends from your first year won’t be the ones you spend your sophomore year with. You’re also told they might become your future bridesmaids.

Sometimes loneliness just lasts a single moment: leaving the library in the dark or eating dinner alone in a crowded dining hall. Sometimes it is the feeling of all the pressure on your shoulders at once—the grades, the appearances, the weed-outs, the life, the career.

Ironically, the technology that keeps us connected to our parents and high school friends also reminds us of how alone we are. We judge our internal feelings by the standards of others’ well-curated social media lives. Completely surrounded by people, we can feel completely alone. The people that we never see after class or outside of a club remind us that most of our friends are those of convenience: I’ll be your friend if you’ll be mine so neither of us stands here looking lost.

Vanderbilt is a contradiction: it is a wondrous place bursting with brilliant, kind minds, yet many find it so very hard to keep going. We might find our best friends and form lifelong connections with them, but we still sit alone in large lecture classes or eat dinner while scrolling through our phones, wishing we were the smiling groups of girls we see.

At Vanderbilt, you can be surrounded by people and still feel completely alone.

There is also the loneliness of coming-of-age during a pandemic. It is a distinct loneliness and grief that come from constantly being in a state of crisis. It is a loneliness that comes with realizing that you were forced to grow up, to change, to lose holidays, moments, friends, family. After being locked in my house and dorm for my late teen years and early twenties, I’m not sure I completely understand my own identity.

Everything about our growing up has been so extraordinary that I don’t know who I am in regular, ordinary, precedented times.

A Making Caring Common national survey found that the pandemic worsened this epidemic of loneliness. The survey concluded that young adults are reporting higher rates of loneliness, anxiety and depression. Sixty-three percent of young people aged 18-25 reported serious loneliness, feeling lonely “almost all the time or all the time” in the weeks prior to the survey. About half of the young adults reported increases in loneliness since the outbreak of the pandemic, and half of the young adults surveyed said nobody in the past few weeks had asked them how they were doing in a way that made them feel the person “genuinely cared.”

The pandemic was lonely when it began; now it feels almost unbearable. Two years after everything started, I am still surrounded by people getting sick. This past month, my roommates tested positive for COVID-19. My own siblings got COVID-19 shortly after I left for the new semester. Like most others, my past 23 months have been a series of COVID-19 scares, tests, vaccines and headlines. I have been patiently waiting —for scientific breakthroughs, for variants to end, for normal to return.

In 2021, a national emergency was declared by several pediatric health organizations and the U.S. surgeon general released an urgent advisory. Between March and October of 2020, the CDC reported that the proportion of mental-health-related emergency room visits increased by 24% in children aged 5-11 years and 31% in adolescents and college students compared with pre-pandemic visits.

The pandemic has exacerbated a mental health crisis that puts America’s youth at risk.

Loneliness can make us feel unworthy. I am still worried that admitting to loneliness will mark me as pathetic or drive away the very connection I desire. Admitting to loneliness when surrounded by loving friends and family feels even more like an admission of imperfection. How can you be lonely when you are surrounded by people who love you?

More than any other emotion, loneliness feels like a personal failing– and we all know how Vanderbilt students feel about failure. This reluctance to speak of loneliness contributes to the false perception that everyone is doing everything so much better than we are. Loneliness is not a medical diagnosis, although maybe it should be. At times, it feels like it might kill you.

At Vanderbilt, we can work to normalize conversations about loneliness with peers. When we prepare to go off to college, we don’t talk about feeling lonely. We don’t talk about how overwhelming it can sometimes feel to take a full load of difficult courses, make friends, participate, give back, be a good person, take care of yourself and not get COVID-19 all while trying to have “the best four years” of our lives.

If there’s one thing that I’ve learned, it’s that we should give ourselves permission to be sad, frustrated and angry. If you are lonely today or are carrying the hurt of lonely days past, I feel you. We all do. It’s essential that we get better at recognizing when we are lonely and learn to share and understand that feeling. We can learn how this heavy feeling weighs on our bodies and our minds. Our loneliness may be able to teach us about the nature of our desire for connection.

Long-distance running is lonely. I’ve learned that isn’t always a bad thing.

Running can be a haven when you just want to be alone, removed from the pressure and obligation of socialization and free from forced interaction. Solitude allows you to learn more about yourself. It allows you to pay attention to the little things– like the sound of your footsteps, the smell of bagels toasting at a cafe on twelfth avenue, or the song you’re listening to.

Once we are attentive to our loneliness, we will be less afraid to speak it out loud. We may even begin to appreciate it.