Maryland-born emcee Substantial had cause for suspicion when he answered a strange phone call from a thickly accented man after a long day of work.

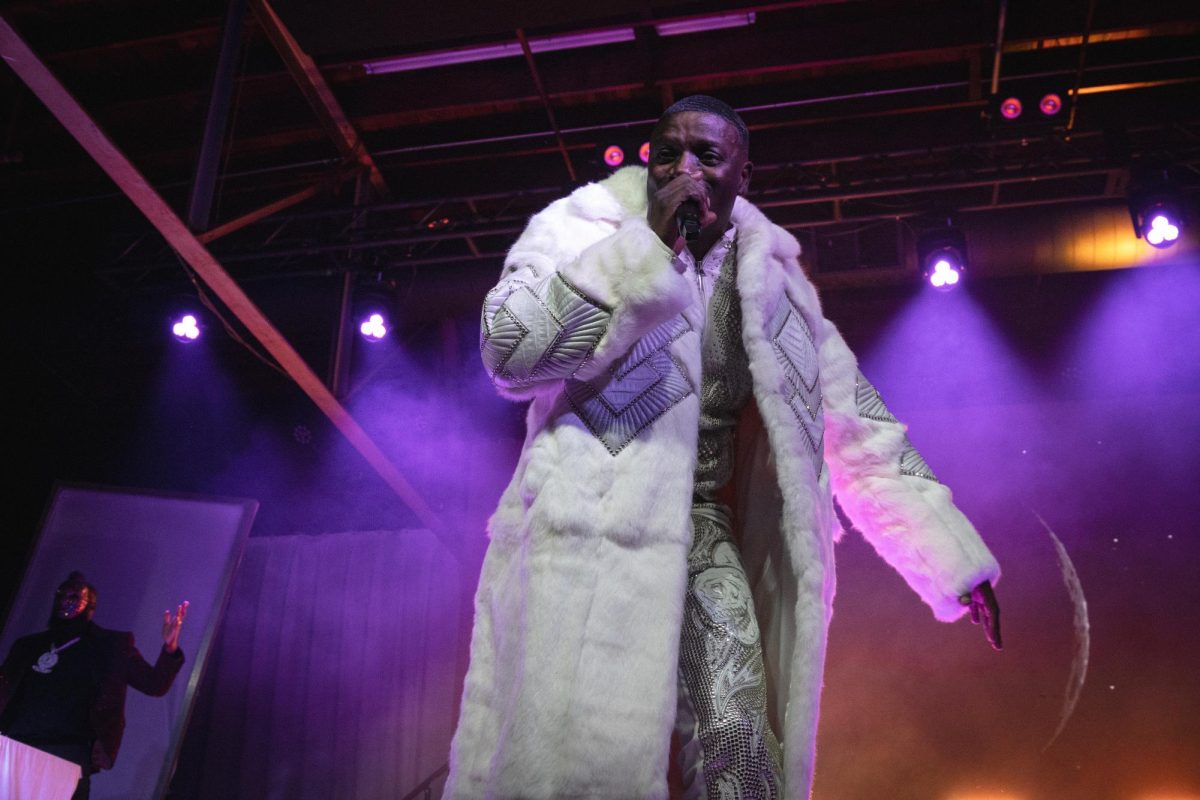

“At the time…I [didn’t] know who he was, and I know my friends are clowns, so I thought it was one of my friends being a dickhead [and] I almost hung up the phone,” recalled Substantial at a concert in 2016.

What he never expected, however, was that instead of offering him a chance to mingle with “hot singles in his area” or tech support at the cost of his social security number, the caller, who was an up-and-coming Japanese hip-hop producer, offered Substantial the opportunity to make music with him on a new record deal with his label, Hyde-Out Productions.

This mysterious figure would go on to craft a revolutionary auditory aesthetic that would lay the foundation for a new subgenre of hip-hop listened to by the millions. His name was Nujabes and he was the godfather of lo-fi.

His Roots

Born Jun Seba in 1974, Nujabes grew up in an era when the hip-hop genre was beginning its meteoric rise into the pop-culture consciousness. When he was in his mid-20’s, starting his career as a music producer, hip-hop was already a cultural phenomenon, with its reach extending across the Pacific Ocean to his hometown, Tokyo. Nujabes was heavily influenced by the East-coast style of hip-hop popularized by artists like Jay-Z, Nas, the Wu Tang Clan and Biggie Smalls, but the difference between his style and that of his inspirations lies in the unique musical atmospheres he created.

East-Coast hip-hop artists were known for their abrasive and hard-hitting lyrical content, painting graphic vignettes of their rough upbringings, and engaging in lyrical fisticuffs against rival rappers in highly publicized feuds. Nujabes, in contrast, produced music with a far less aggressive and cynical tone.

Nujabes enlisted the lyrical talents of Substantial to draw distinctions between his music and that of his western counterparts in the track “Think Different.” While Substantial takes verbal jabs at members of the hip-hop mainstream (“you suckers are vandals, we’re graff’ artists/thought you had the last laugh, but we laugh hardest” and “you try, I do/I’m wise, you’re clueless/I get the job done, you fail and make excuses”), he highlights a desire to spread wisdom over violence (“You bust lead? So do I/Except mine impregnates the page giving birth to thoughts that unify”) and an inclination towards emotional sensitivity years before Kanye made it cool. “Think Different” is a unique kind of diss track that swaps vitriol for vision, as Nujabes and Substantial acknowledge that despite the stylistic differences to east coast rappers, they are collectively contributing to the hip-hop genre with their own unique perspectives.

“Is the glass half-full or half-empty?

It’s based on your perspective, quite simply

We’re the same and we’re not; know what I’m saying? Listen:

Son I ain’t better than you, I just think different”

An aspect of East Coast hip-hop that had the greatest influence on Nujabes’ music was its signature boom-bap style of production. The term “boom-bap” is an onomatopoeic term referring to the subgenre’s distinctive drum patterns, which consists of deep and punchy bass-fueled “booms” on the downbeats and light and crisp snare-fueled “baps”on the upbeats. Boom-bap artists tend to employ grittier and grimier beats whereas Nujabes’ beats are, by contrast, silky smooth. They blend new-world production styles with old-word sampling to create a tonally nuanced soundscape permeated by a peaceful, yet bittersweet sentimentality, a tone that is a framework for countless contemporary lo-fi beats. For example, Nujabes adorns the aforementioned track, “Think Different,” with a shimmering piano riff from an excerpt of the soundtrack for a 1960’s French film and layers it with a boom-bap drum pattern, which contributes a stern sophistication to the track.

“Along with J Dilla, [Nujabes] brought in this idea of mixing genres together, especially boom bap and jazz. I know that they come from the same culture and have been used together before, but I think the fact that someone in Asia managed to just combine those genres and make it sound so different was very important for the [development of the Lo-Fi] genre,” first-year Daniel Park said. Park also makes music as a Lo-fi producer under the name Parxed and a member of the indie band Bittermilk.

This synthesis of styles is exemplified in the track “Brothel Love,” as Nujabes loops a wistful six-second piano motif from a relatively obscure 1980’s jazz song over pulsating drums to create a melancholic mood. However, what elevates the track is a tertiary sonic layer in the form of what appears to be metallic sloshing of water inside a bucket, which establishes a fluid and abstract cadence that contrasts the track’s static percussion and melody.

“[Nujabes’] usage of things like sampling and ambient and environmental sounds is a huge thing that a lot of people enjoy because one thing that the current generation that I think enjoys is relatability. Like even on YouTube, I see that vlogs are so popular because you’re looking through the lens of a different person…when you add this kind of element into the music, you add relatability … [immersing] yourself more into the music and perspective of the artist,” first-year Liz Chun said.

His Style

While Nujabes would operate in relative obscurity throughout the early stages of his career, his beats and music made waves within the Japanese underground hip-hop scene, eventually catching the attention of director Shinichiro Watanabe, who is no stranger to genre blending himself.

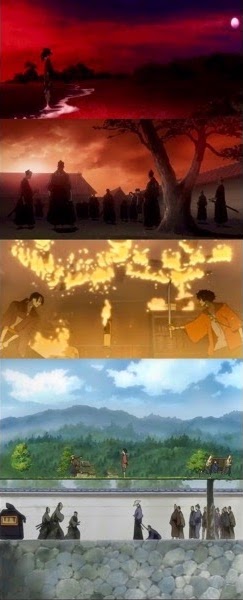

Having already created the cultural phenomenon that was the anime “Cowboy Bebop,” which combines elements of science fiction, westerns and jazz music, Watanabe was now looking to create a new show that fused themes of hip-hop and Edo-era samurai titled “Samurai Champloo.” This show would eventually go on to develop a massive cult-following and give Nujabes the opportunity to present his work on the global stage.

“The composer Nujabes was the first name that came to mind when I thought of creating music for ‘Samurai Champloo,’ so I think we were able to perform a great, spectacular collaboration together. I had a dialogue with him after we finished working on the show. Until then, he was exclusively working in Japan, but after ‘Samurai Champloo,’ he got a lot of great positive feedback from many people outside of Japan, so he was very happy with that,” Shinichiro Watanabe said in a 2013 press conference and public Q&A.

The aptly titled “Samurai Champloo,” with “Champloo” referring to the Okinawan word for “mixed up,” centers on the exploits of a pair of samurai, consisting of the fiery and flamboyant outcast Mugen and the cool and collected ronin Jin, whose contrasting personalities are balanced by a young girl named Fuu, who unites them on a quest to find “the samurai who smells of sunflowers.”

Their dynamics closely mirror the beat composition of Nujabes, as he balances spunky drums with soothing samples for a distinctly vibrant, yet mellow mood. As the primary composer behind the soundtrack for “Samurai Champloo,” Nujabes crafts beats that bring color to the show’s sleek animation style and brilliantly choreographed action sequences.

The seamless synergy between “Samurai Champloo” and its soundtrack is in full display during the closing scene of the show’s eleventh episode, “Gamblers and Gallantry,” which sees Jin rescuing Shino, a woman who is sold off by her husband to a brothel to pay for his debts, under the backdrop of the Nujabes’ “Counting Stars.” In this track, Nujabes samples acoustics from a 1970’s Latin-funk fusion song by José Feliciano of “Feliz Navidad” fame.

Instead of conveying a more energetic and festive tone like the original song, Nujabes takes advantage of the guitar riff’s minor key and pairs it with a faster paced beat and harmonizing strings to convey a sense of urgency that perfectly complements the fast-paced sword fight. Sprinkling in some vocal samples of Frank Sinatra, solemnly singing phrases like “it could happen” and “don’t count stars”, also adds an ominous undertone, almost as if Nujabes is trying to show listeners a darker side to wishing upon a star.

“I think the way he’s able to always find samples from a very vast and diverse array of different styles of music and kind of take a focal [point] of that sample… and stretch it to a sort of main theme… adds a very special flavor to his music,” Chun said.

While he wasn’t the first to incorporate recorded excerpts of other songs into his music, Nujabes was famed for refining the art of sampling by putting his own stylistic imprint on musical motifs. As the owner of multiple record stores, he has access to an extensive range of records and spent countless hours create-digging in search of the brief snippets that would lay the foundation for his beats.

Most notably, the track “Aruarian Dance” features a musical motif interpreted by four different artists of four different genres in the span of a century. Its story begins in Paris of 1899 where a young Maurice Ravel composed the French Impressionism classic “Pavane for a Dead Princess.” In 1939, American jazz singer Mildred Bailey sampled a fleeting three second snippet of Ravel’s piece in the chorus of the hit song The Lamp is Low, which would then be covered by Brazilian guitarist Laurindo Almeida three decades later. Almeida’s cover of a song that sampled a classical piece would eventually land in one of Nujabes’ records stores, waiting to be discovered and reworked into the most popular track on the “Samurai Champloo” soundtrack.

In “Aruarian Dance” Nujabes manages to retain elements from the entire network of samples by reusing and arranging Almieda’s acoustics, developing the musical motif selected by Bailey with subtly incorporated instrumentation, while maintaining the feelings of mournful longing that reflects the tone of Ravel’s Impressionism classic, all while combining those elements with the pulse of boom-bap hip hop in the signature Nujabes style.

Nujabes was not only able to impact the technical construction of lo-fi hip-hop through his usage of unique sonic textures and creative sampling, but also showed that his style of production could balance various distinct tonalities, inspiring diverse subgenres within lo-fi.

“‘Counting Stars’ is very fast paced and sounds like something is rolling along … constantly in motion. ‘Aruarian Dance,’ on the other hand, is more flowy and downtempo. It’s very similar to how the ‘summer’ and ‘winter’ lo-fi [subgenres] differ, because on one end you have this more energetic style while on the other end you have a more chilled out kind of mood,” Park said.

While many of Nujabes’ production techniques have significantly influenced the lo-fi genre, he is not necessarily considered a lo-fi artist himself. Lo-fi is an abbreviated term for the phrase “low fidelity” and refers to a production style that focuses on degrading the sound quality of music through distortions and artificially creating an “analog warmth.” Nujabes rarely altered the sound of samples, instead opting to splice bits and pieces of the original music and place them in creative contexts, giving them a distinctive sense of purity and authenticity that many have tried, and failed, to replicate.

“If you deconstruct his composition, you’ll find there’s not that many moving parts to it … while lo-fi involves a lot of altering, his alterations are very minimal.” Chun said.

His Legacy

Nujabes’ career was tragically cut short when he passed away February 2010 at the age of 36 in a traffic collision.

“We deeply regret the loss of a unique talent and a close friend. Through his soulful music, Nujabes has touched so many people around the world, even beyond his dreams. He was a mysterious character to most as he avoided the public limelight, rarely conducted interviews, so only a few got to know the man behind the signature production. Yet it continued to amaze me how young listeners of all backgrounds learned of his enigmatic name, and expressed support for his music,” said longtime collaborator Shing02 in a eulogy posted on his website.

Personally, I have always felt that there was an impressionistic kind of ambiguity to the music he made. Whenever I listen to his music, I find that his songs will often tailor themselves to how I feel at a given moment: consoling me through times of pain, cheering me through times of success, calming me through times of confusion. Perhaps this is why Nujabes appealed to such a wide range of people.

One quick scroll through the comments section of an hour-long version of “Aruarian Dance” on YouTube helps grasp the impact of just one of Nujabes’ many beats. Among the thousands of comments, there are sleep-deprived students thanking him for providing a calm musical soundscape to dwell in as they pound away at assignments, aspiring artists telling their stories of how his music changed their lives and pushed their careers into a bold new directions, and those enduring great hardships, using his music as a sanctuary from the unforgiving nature of human experience. Even in death, Nujabes’ spirit lives on in the hearts of the countless people who have been soothed and stricken by his music’s soulful splendor.