I was 12 years old when I first heard “Crank That (Soulja Boy).” There was a violent hailstorm raging outside of the local Boys & Girls Club where I was attending summer camp, and while we were all locked indoors until the weather cleared up or our parents came to take us home, several of the counselors agreed to pop a copy of Dance Central into the company Wii system to help us endure the wait.

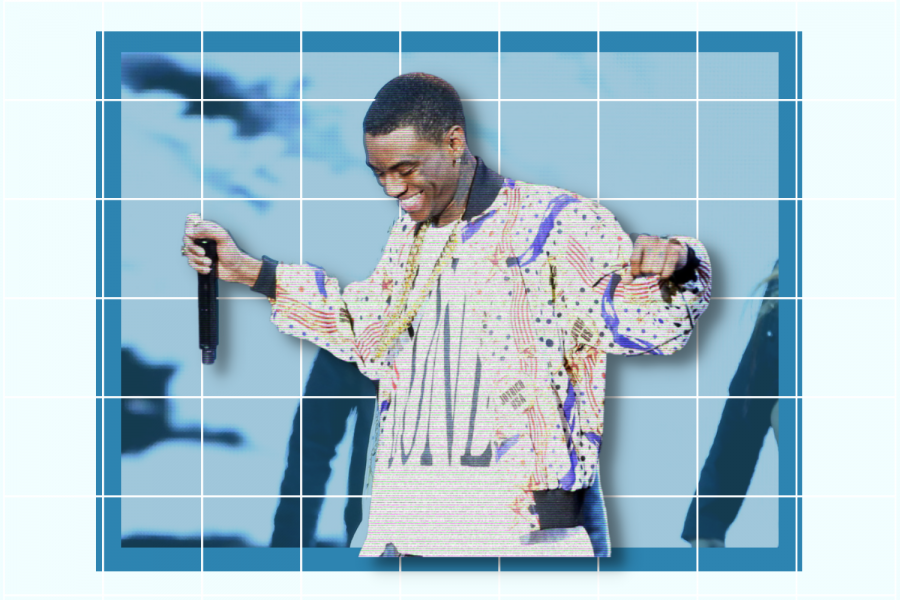

Hearing “Crank That” for the first time was like being brainwashed into an all-exclusive way of being, solely accessible to believers in the swagger it exhibited: it was more of a chant than an intricate array of bars, more of a visual experience than an auditory soundscape, more of an open-ended celebration than a one-way flex—but more than anything else, it was simple. It was catchy. Just because it seemed as if anyone could, I wanted to be just as swagged out as Soulja Boy when I grew up. I sat wide-eyed, staring at the television screen, my slightly older peers religiously reenacting the dance moves in my peripheral vision—jump-crossing legs, touching toes behind backs, hopping on single feet with arms outstretched backwards like collective Supermen. Though my dad arrived to take my sister and I home several verses before the video game was over, by midnight that night, I had memorized the entire song.

Soulja Boy’s initial ascent to prominence banked on this accessible quality—anyone who wanted to participate was allowed full entry into his promising new revolution. Where previous decades saw hip-hop culture strictly adjoin itself to corresponding gang scenes and street politics, losing favor with protective parents nationwide, 2007’s “Crank That” marked one of the first times in the 21st century that you could spot preschoolers dancing along to a chart-topping rap song—with their caregivers not only supervising, but recording on their cell phones. Soulja Boy’s emergence into the world of contemporary culture both coincided with and epitomized a novel blog era, one that had just begun to stem from burgeoning ties between urban music and the internet (which was, at this point, no more than two decades old). All of a sudden, fans from all around the globe were in touch with each other. Just a couple of years prior, one essentially had to keep their weird music opinions to themselves, but with the advent of the world wide web, ideas and fandoms began to proliferate at historic levels.

“Throughout the early 2000s, a couple hundred superfans flocked to two parallel, overlapping web forums—the official Star Trak forum and the rawer fan-site theneptunes.org—to swap behind-the-scenes info, post unreleased band demos, and soak up knowledge that they’d go on to pour into their own creative endeavors,” former New Yorker editor Matthew Trammell wrote in an article about forums dedicated to the band N.E.R.D. “Many frequent users went on to lead global cults of their own: alums include M.I.A., Drake, Janelle Monae, Tyler, the Creator and more. N.E.R.D’s forums not only served as a talent incubator but also planted the seed for the industry’s full turn toward the internet as the primary means of music distribution, criticism and debate, and direct-to-fan engagement.”

“Crank That,” in and of itself, was simultaneously an epitome and beneficiary of the internet’s unfurling mode of operation: everyone was included; traction sprang from consumer rather than producer; there was more room for conversation between rapper and audience, and less room for the rapper telling the audience how cool he was. When Soulja Boy howled “Youuuu,” he was talking to you. When he told you to watch him “crank that Soulja Boy,” the virality depended on you relaying the message to someone else. And even between the lines of brash declarations like “you can’t do it like me,” there existed a hidden “but I’d like to see you try.” Soulja Boy loved (and lowkey invented?) the internet. The internet loved (and lowkey invented?) him back.

But now it doesn’t. Last month, Soulja Boy tweeted a link to purchase an NFT depicting him as an angry ape. While his original tweet capped at around 500 likes, the first reply—a meme that read “NFT artists be like: this pic goes hard, $4,500 to screenshot”—is, as I write this, at 1.4k likes and counting. It wouldn’t be the first time that Soulja Boy has made a fool of himself on the very platform he once championed. Other examples, painful to recall as a longtime Soulja Boy apologist, include his obscure video game console “SouljaBoyGame,” the impassioned Breakfast Club rant that turned him into a recurring hip-hop punchline and an overall embarrassing Twitter beef with the WWE wrestler Randy Orton.

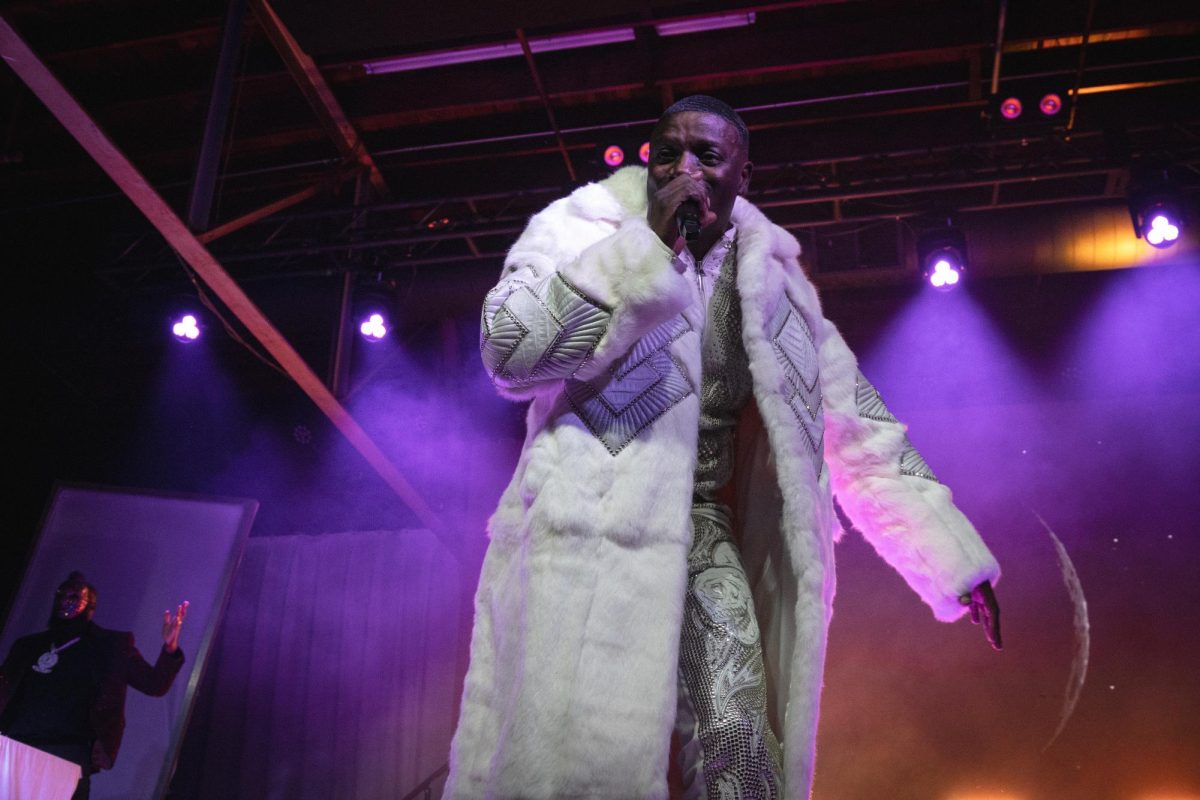

Over a decade removed from his internet-dependent rise to glory, Soulja Boy seems to have cast all self-awareness into the same void his legacy is dying in. Like the starved Nintendogs that rot away on our dustied 15-year-old DS systems to this day, his dignity is thrust more and more irrecoverably into famine every time he opens his mouth. It’s a classic case of boy-who-cried-wolf: at a certain point, people realized that he wasn’t saying anything of substance anymore and simply stopped listening.

It’s even come to a point where the dynamic constantly plays itself out on a micro-scale. I, along with many others, for instance, used to live for his brazen assertions that he was the “first” to do a host of things. Hip-hop accounts photoshopped images of him setting foot on the moon; his tweets went viral; comment sections began to agree that it was time to give the man his flowers. But once he had the people’s attention, he started overusing the joke. Then, his “I was the first” statements started becoming completely incorrect … and at some levels, outright disrespectful. Soulja Boy’s career at large has taken the same exact pitfall: He attracts an audience. His mouth starts running. Then—straight out of the classic refrigerator prank call—he can’t catch it.

So what if he just closed the void?

If Soulja Boy had never spoken again after 2007, it is very likely that we would consider him two things: a one-hit wonder, and a legend. One of the few common truths of the 20th century and the internet era alike is that once an artist stops talking, the audience starts desperately trying to fill in the gaps—and not according to objective realities, but instead to whatever upholds the last image of the artist they’re familiar with.

When MCs like Kendrick Lamar and Frank Ocean go quiet for years on end between groundbreaking albums, their silence contributes to a certain untouchable mystique, one that renders the possibilities limitless while leaving their legend intact. Nothing an external figure says about, or does to, a musician can definitively and totally tarnish that musician’s perception—if it could, being a music critic would be a great alternative for someone like Mark David Chapman—because at the end of the day, until the artist opens their mouth, it’s all just hearsay. Maybe Pitchfork says they’re working on a new project. Then, maybe that one YouTube channel run by your ex’s music-head friend says they’re hiding out in Japan. And maybe a pair of Twitter users are going at it about whether they’re remastering demos or taking time off to focus on family. None of it is of any value until the figure themself is there to give the final word.

In a climate where more opinions are flying around than ever before, any shot at long-term respect requires a solid, coherent legacy onto which these opinions can latch. A common adage advises that it is “better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.” In this sense, Soulja Boy has committed the greatest sin: not only did he speak after 2010, but practically every time he did so, it was nonsense. We didn’t have to know he was a bum. But—even if you’ve been rooting for him all along—there’s no longer any doubt left.

Soulja Boy is living proof that, for as much as the music industry has changed, one’s music still has to be able to speak for itself. But in order for the music to speak for itself, one must actually let the music speak. For the past 10 years or so, Soulja Boy hasn’t been letting his music breathe. It’s not like he’s a bad rapper. His 2007 debut album “Souljaboytellem.com” was the soundtrack to some of my richest childhood memories; over 10 years later, his earworm single “She Make It Clap” is a TikTok darling.

Yet Soulja Boy’s problem isn’t his music; it’s his mouth. For every step he thinks he climbs up the internet ladder he pioneered, the previous rung falls out from beneath him—and by the time he gets the sense to stop talking and look down, there will be nowhere left for him to go.

Back on Earth, the same kids who danced along with his music videos 10 years ago will have grown up. They will crane their necks at the spectacle flailing in mid-air. They will shake their heads in disapproval. Then they will go back to what they were doing.