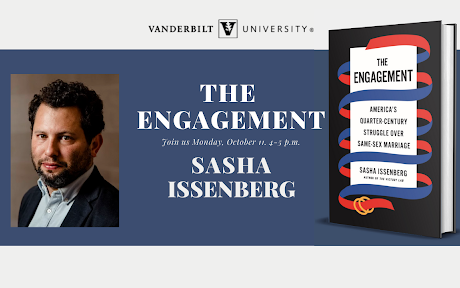

On Oct. 11, The Hustler sat down with Sasha Issenberg, a political journalist specializing in campaigns and an author of four books, to discuss his most recent book “The Engagement: America’s Quarter-Century Struggle Over Same-Sex Marriage.” The book was published in June 2021 and delves into the history of LGBTQ+ rights, highlights key figures behind the fight for marriage equality and considers how America’s religious history factored into the legislation’s timeline.

Issenberg visited Vanderbilt on National Coming Out Day as a key part of Vanderbilt’s LGBTQ+ history month programming, per Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs C. Cybele Raver. Issenberg discussed his writing process and the present state of the LGBTQ+ rights movement.

Vanderbilt Hustler: What inspired you to begin writing and researching about the legalization of same-sex marriage?

Issenberg: I had the idea about 10 years ago, and I guess a couple of things were going on then that led me to it. I was working on my book called “The Victory Lab”—which came out in 2012—about the science of political campaigns. I was having a lot of conversations with pollsters or people who, in some form or another, measure public opinion, and over and over again, they’d say that they’ve never seen attitudes on a single issue move as quickly as they’d seen them move on marriage. I’d covered politics long enough to know how difficult it is to durably shift opinions on something like that and how rare that was to see them move all in the same direction across the population and that just struck me as a really interesting puzzle that nobody had a really good explanation for.

We were starting at that point to talk about this as the defining civil rights movement of my generation. I’m 41 now, I was 31 then. I had no idea how this issue had sort of emerged as not just the dominant LGBT rights issue but the dominant area of cultural conflict and probably the most successful social movement of its time. I was surprised that nobody had written about it. I tried to piece together that whole story and so that’s what I set out to do.

You said your interest in this topic was piqued by how quickly public opinion started shifting on this issue, what would you say the main catalyst for that change was?

Today is National Coming Out Day [and] a huge part of it is people coming out and others around them recognizing that they know somebody who’s gay or lesbian. There’s a fair bit of research that suggests that the biggest driver of liberal attitudes on a whole bunch of gay rights questions, not just on marriage, is how somebody answers the question “do you know someone who is openly gay or lesbian?” I think that there was eventually sort of political and legal successes on top of that social change, but it’s impossible to get to the underlying social change without recognizing how much more common it is for people all over the country to be in regular contact with folks who are gay or lesbian and then ultimately realizing how modest a demand it is, from the state, to recognize the relationship you’re in.

Can you describe more about how your past experience as a journalist writing about topics such as political campaigns and globalization inform or aid your writing process for this new book?

The place where there’s the clearest overlap between my past books and this one is a big part of the story of the marriage equality side of this conflict was that they got much better about doing politics and legal work around the issue, especially in the period between 2008 and 2012. A lot of that is a similar type of story that I told in “The Victory Lab,” which is about finding ways to measure what works and what doesn’t in the campaign, using all the new data that’s available for political campaigns, research tools to test what works and what doesn’t. There are actually even a few characters, people, I interviewed initially for “The Victory Lab” who play a role in this story because this is one of the issues when that type of innovation I think really paid off. The campaigns that were being run in 2012 looked very different than the ones in 2008 and that was because people went in and said, “we know that what we’re doing isn’t working and we need to figure out how to do better.” Luckily, there were some very large donors within the gay rights movement who were very invested in finding that work at that time.

Do you think politicians have shifted their opinions about same-sex marriage because of the changing broad public opinion? If not, what caused this change?

In the long arc of this story going back 25 years or so, it is an issue where, I think, largely politicians have lagged behind followed public opinion. Probably the most famous example of this—one that I spent a fair bit of time in the book on—is Barack Obama, who I think had a change his position very publicly, only not so publicly on marriage. He went from an early supporter of marriage rights to an opponent and then a supporter of civil unions and then to, again, in 2012, a supporter of gay marriage. I start trying in the book to reconstruct Obama’s evolution on these issues over the course of his political career and he had a very good nose for being on this issue in particular, always in this sort of safest place given whatever the key constituency was that he cared about at the time.

When he was running to represent a fairly liberal state senate district around the University of Chicago, he said that he was in favor of same-sex marriage. In 1996, when he was running for Congress in the district that was in a Democratic primary, where church-going African-Americans were the key constituency, he was opposed to same-sex marriage. Then, what pushed him in 2011 to basically tell his advisors that he was ready to change his position on this was that he was feeling out of sync with the Democratic Party that was gonna renominate him for a second term.

I think we’ve seen versions of this for a lot of politicians having an evolution that’s been very rarely them coming out and taking what was an unpopular position on either side of this issue. At various times, it was very rare that there wasn’t a politician and a very good idea of what the people that they cared about were thinking on this issue.

Do you feel as though American universities adequately educate their students about LGBTQ+ history? If not, where is there room for improvement?

That’s a great question, and although I do a little bit of teaching, I do not presume to be an expert. I think that the important thing is making sure that LGBT history is synthesized into American history and the study of American political institutions and not just offered as its own area of study.

I sort of accomplished this with this book—yes, it is an account of the debate over the fight over marriage reigns, but, in many ways, it’s about the conflict over sexual politics and culture wars over 30 years because this became the primary area of conflict for a large part of that time. In many respects what I tried to do is have a story that was about something I think is a pretty good story about American religious politics over the last 30 years, one that is about lobbying interest groups about how campaigns have changed. It ends up being that this marriage story is the vehicle for news.

I think what’s important is just to make sure that we’re not just teaching and offering courses and LGBT history but making sure that these conflicts are being called in canonical American history, in the same way that we study the Civil Rights movement, and not as just in African-American history courses. We realized that to understand American politics, economics, culture and society today, we need to understand how questions about race, segregation and racial power have played out.

What is the importance of Tanco v. Haslam, the court case on same-sex marriage that originated in Middle Tennessee to the larger fight for the legalization of same-sex marriage? Does this case have heightened relevance for members of a university located in Middle Tennessee?

The 2015 Supreme Court heard four cases that are consolidated from the same appellate circuit, which included one case from Michigan, one from Ohio, one from Kentucky and one from Tennessee. They all basically presented the court with the same question, which was, “can a state ban same-sex marriage?” or “where can a state restrict access to marriage to same-sex couples?” It’s possible that they could have split those up into different things, but they didn’t; they got to the core question.

I think it is sort of analogous to the way that it ruled on Loving v. Virginia, the case that said in 1967 that you cannot use racial qualifications in determining who can marry. The court ruled in 2015 that you cannot use sex or gender basically as a criterion for setting qualifications for marriage. There had been something like 35 states which at some point had explicitly banned same-sex marriage in their constitutions, and another seven or eight states which had not taken a proactive step to legalize. The court said, “under the U.S. Constitution, you cannot do that.”

It is an important fact of history that part of that case came from Tennessee, but ultimately it affected Tennessee the way it affected 15 or so states that were still outliers. There are two parallel tracks that this conflict played out. Some states chose through their own courts or their political process to let same-sex couples marry. Massachusetts was the first one to do that in 2004. Other states followed, of course, with legislature through ballot measures, and other states went through their political process and said, “we very explicitly do not want to recognize these relationships.”

We could have very easily ended up in a country where some states had allowed same-sex couples to marry and some didn’t and the court could have said that that was fine. Historically, the federal government has given states power extremely when it comes to all sorts of issues related to marriage. It’s only in really extreme cases when the federal government has stepped in and said, “We’re going to tell states. We’re going to give sort of boundaries on your marriage rules.” So, it was really remarkable in the long arc of American history. This is one of those rare places where the federal government stepped in and said, “no, you cannot say your own rules about who marries because these rules directly contravene guarantees in the Constitution.”

That Tennessee case and the other three that were consolidated with it fell in one swoop. All of a sudden people had the right to marry and you know that momentous day in June 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled and the White Houses lit up in rainbow colors.

That case was followed by normal people who saw that a state law discriminated against them and decided, with the help of civil rights litigators, that they were going to challenge it in court, and saw that all the way through to appeal to the Supreme Court as they lost it at the appellate level. They sort of soldiered on with it. I think just recognizing being students here, not far from where some of the couples who filed live, it’s important to recognize that there are real people, individual people, like individual lawyers, who are doing the work that leads national social change.

I think one of the things I wanted to do with the book maintained that human scale in telling the story and not just telling this big sweeping national epic, which it often is.

In a time after the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, do you believe that the fight for same-sex marriage equality in America is over or still ongoing? Why or why not?

I think the big fight about whether same-sex couples will be able to legally marry is over. I think that what we have seen is that the side that lost before the Supreme Court in 2015 basically conceded defeat very quickly. I was surprised by how quickly the opposition was defeated, as with many of the organizations that had been fighting for recognition for same-sex marriage. I was surprised, in part, by how little of a political issue it was, even within weeks of that court decision.

What we have seen in the last few years are a number of cases about religious liberty religious freedom exemptions. There was one case from Colorado which is about a baker who said it violated his biblical teachings to make a custom cake for a gay male couple that married there. More recently, this past term, a Philadelphia Catholic social service agency had a contract with the city to place foster children and families and said that they would not place foster children with same-sex couples.

In both cases, the court sort of evaded the big question. I suspect we are just at the beginning, and we will see a lot more of these cases. This is a court that’s going to be very receptive, I think, to these claims that private actors do not have to treat all narratives equally if they have a religious basis for doing so. I think the question is how far those exemptions go and whether that dramatically changes what it means to be married in the United States—if your employer or educational institution or some community organization or a public accommodation can say, “because of our religious values, we will give different benefits to be married, same-sex spouses of our employees than we do to opposite-sex spouses of employees.”

I think that this is going to be a multi-year, if not longer, conflict. But I do think of it as a sort of fundamentally different conflict than the question of, “do the laws recognize couples equally?”

How do you think modern political figures such as Pete Buttigieg and Jared Polis have played into the intersection of politics and LGBTQ+ rights?

It’s remarkable how little their sexual orientation has been a factor in their political identity. Pete Buttigieg is married to a man, which was barely talked about over the course of his campaign as a central part of his political profile. When Jared Polis got married, it was treated as, “oh the governor got married.”

I think it’s one of the ways in which cultural acceptance is just really evident, whereas if you went back even a decade I think it would have been almost impossible for media coverage and other political figures to engage with them without that being the kind of central or seen as a central part of their identity. I think it’s the last room of a bigger trend which is same-sex families are an accepted part of American life now in a very uncontroversial way almost everywhere and at all times.

I think the fact that you have those politicians and it does not seem like they have to spend a lot of time talking about it, is just evidence of how accepting things have become.

Content has been edited for brevity and clarity.