As I sat in one of my Zoom classes early last week, I found myself constantly staring out of the window. I rocked back and forth in my chair a bit on edge, trying my best to grab something near me while still paying attention, to ease my fidgeting fingers. As I half-listened, I toyed with one of the dangly earrings that I hung from above my desk, working the metal chain in between my fingers, struggling to focus my eyes on the professor’s video.

Every time I was called on I got the answer wrong. I knew the material. I was prepared. But I couldn’t shake the feeling: the wave of sadness that clouded my brain and the question of why not one professor had asked if we were okay. If we wanted a day off. To grieve. Did it even shake them? Or like any other hashtag, was it—was he—just scrolled over? Do they, professors, even feel like they have time to process?

Move on to the next tweet. Next story. Next class. Daunte wasn’t related to you or anything. Neither was Adam. Or Ma’Khia. You didn’t know them. Let it go. Get off your phone and focus.

That week in March I didn’t want to go to class. When the Atlanta shooting happened. I struggled to keep my composure in class, sick to my stomach over the lives of the six Asian women who were taken: Soon Chung Park, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Yong Ae Yue, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng; as well as the other victims: Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels and Elcias R. Hernandez-Ortiz, who was seriously injured.

Stop checking news updates. You have to study. Put down your phone. Close The New York Times. You have to go to class. It starts in 10 minutes.

In my time at Vanderbilt, I’ve scrolled through many hashtags: endless names of Black and brown people lynched by the police and have read news time and time again of mass shootings and lives stolen; watching it on a loop, a never-ending cycle, so that the initial shock no longer exists when I read news headlines.

Atlanta, Georgia. Boulder, Colorado. Orange, California. Rock Hill, South Carolina.

All sites of mass shootings since 2021 began.

I’ve also watched Vanderbilt neglect to give us time to grieve. The most has been vigils compressed into lunch breaks or slipped in before dinner. Even in a pandemic as the death toll ticks further and further up, surpassing half a million in the U.S. and three million worldwide, we have not had a single day dedicated to mourning. But then again, our university is just a microcosm of the greater culture of never stopping, never mourning, never breathing, always working. That’s the American way.

A moment of silence in between classes. A lowered flag. A panel discussion. An encouraged trip to the counseling center. That’ll suffice.

In my recollection, it’s only happened a few times: when a professor asked how the class was doing specifically in terms of grief and took action. Notably, once was in an African American Diaspora Studies (AADS) class in which the majority of the students were Black during the summer of racist police-inflicted violence. Another was in a Philosophy course that taught literature intended for political resistance, thus many of the writings were for the purpose of liberation, the abolition of policing, and the rejection of capitalism. And while both of their curricula dealt with ad rem topics, both professors were the type to give us a day off from class to mourn properly and for both us, the students, and them to feel okay enough to participate in the next class discussion. For them, I’m grateful.

Did any of your professors ask how you all were after the horrific Atlanta shooting? Ask how you were processing? If you needed a day off? Was there a break in the lecture? In the class discussion? An email? A Brightspace post?

Yet in these cases, I don’t blame our professors who are still trying to adapt their classes to a pandemic lifestyle and grieve and process and live all at the same time. I blame the capitalistic culture that has convinced us that there is no need to stop and no need to process. It has turned us into zombies: the undead who never received peace. Desensitized. We walk around numb, craving the sort of stillness grief requires that our environment—our rise-and-grind culture—cannot fathom, nor possibly provide.

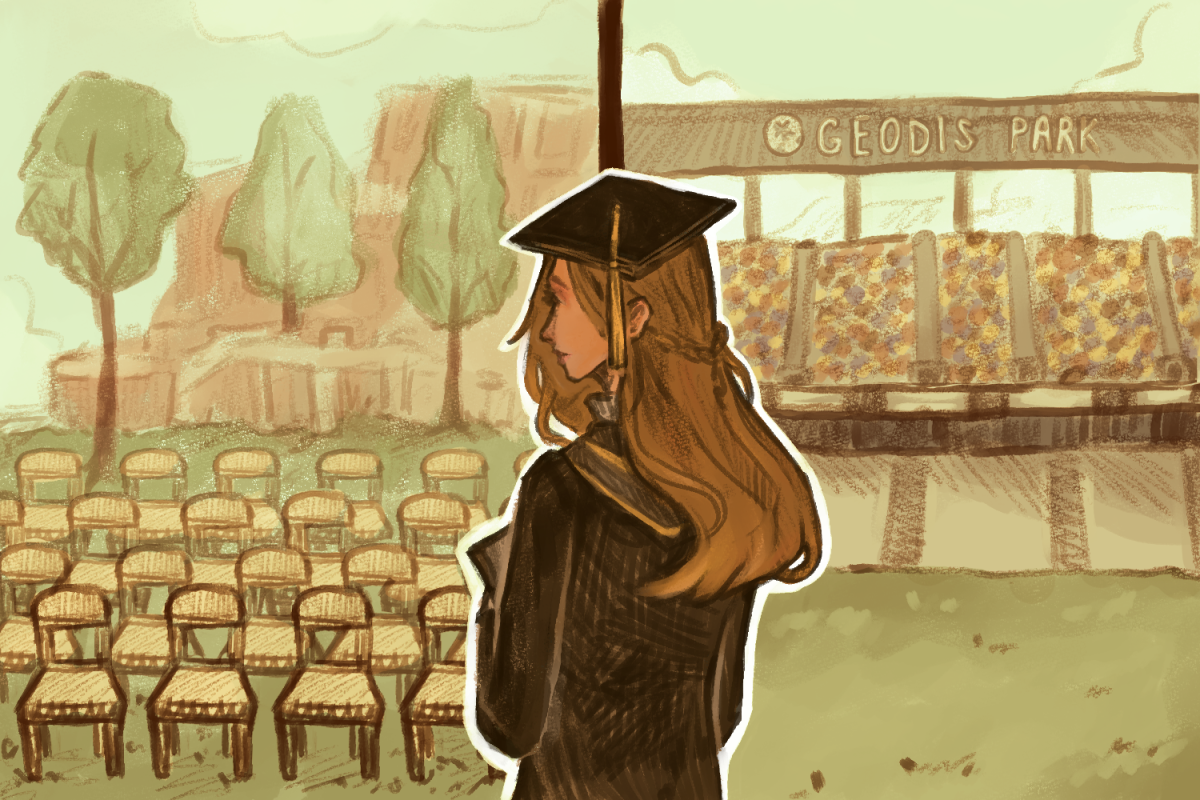

Under this system, death is and will always be profitable. As Medium contributor, Isabel Mares puts it, “Capitalism does not want your prayers without tithes, nor pain without purchasing medicines. Thus, capitalism will only allow for the kind of grief that demands payment. Capitalism only allows for a grief that is a hungry ghost.” On campus, the ghosts look like zombies and they’re hungry for success: the type of grief that makes us succumb ourselves with our busyness and work ethic until the strive for good grades makes us forget that we are in a collective mourn, an incessant funeral. Outside of the library, sits the memorial exhibit that allows us to remember the chairs left empty at kitchen tables. It is beautiful, however, I only get to admire it and feel its weight when I’m on my way to class, dashing from main campus to Commons, before I check the time and have to run.

In many ways, the joys of academia are trampled on as institutions of higher education mold us into workers. We get thrown onto a treadmill, moving at the speed of a workweek designed for the utmost productivity at the expense of the worker. We become workers instead of students and when our education is measured by a means of productivity, the emphasis of digesting the material and immersion into the liberal arts is forcibly removed, and instead, the onus is placed on the amount of work we achieve. Our work time is carved into our calendars, and when learning becomes “clocking-in,” what we do in that time is measured based solely on its social or capital value.

Capitalism persists in other areas of academia. We get put into competition with each other, so much so that after test days during a normal school year, I would immediately jam headphones into my ears so no one asked me how I did to compare scores. We get primped and polished to be the perfect Vanderbilt-bred consultants and investment bankers, so much so that we have not had one day off in the name of the thousands of lives lost in the most deadly pandemic our generation will ever see. What is our worth beyond students, when to be “absorbed in grief,” as Julia Cooper writes in her book, “The Last Word”, “holds no social value?”

Grief doesn’t conform itself into a timeslot within our work schedules.

However, universities are a unique setting because they are like micro-towns. Each residency on campus is a neighborhood, and around us is need-based infrastructure. And while our shield of the “Vanderbilt-bubble” is often discussed negatively, this micro-town-like anatomy allows universities to redetermine what dictates “social value” in their social jurisdiction. Our home on campus can be an experimental site for the change we want to see in the world beyond our sphere. College campuses have been testing sites before for new structures. For example, the way we pay college tuition is socialist economics and equitable wealth redistribution in practice.

Although many problems prevalent on Vanderbilt’s campus are a result of not only administrative decisions but the geopolitical region it sits in and the economic framework it’s placed under, it must be asked why we continue to function within harmful frameworks that don’t give us room to grieve if we are not obliged to operate in this way?

In the upcoming school year—one that will hopefully be without the virus and the wave of death and trauma we have experienced—I hope our university will afford us time: a prerequisite for mourning when we must, for continuing to operate under a capitalist framework that does not give workers time to mourn conforms us into desensitized machines rather than people, and assignments rather than students. And in turn, those we are mourning do not become more than hashtags, developing stories and empty chairs.