Should I book a vaccine appointment? If there are extra vaccines available downtown, should I see if I can get one? Am I taking a vaccine away from a healthcare worker? Aren’t there higher-risk, more deserving recipients of this shot?

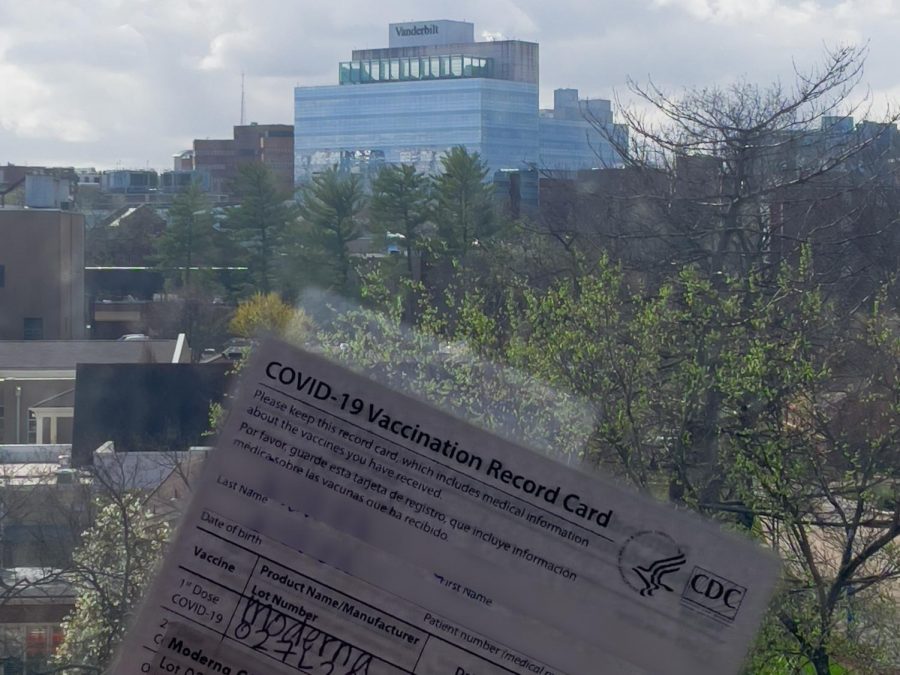

This pandemic is creating ethical dilemmas we have never encountered before—and there are no easy answers. As more and more Vanderbilt students become eligible for vaccination, deciding whether to take an available shot has turned into a moral quandary. On April 5, anyone who lives in a “congregate living facility” is eligible to receive their vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control definition for this includes apartments and student facility housing, which would seemingly include most Vanderbilt students. Many college students across the nation have already begun to be vaccinated at Walgreens locations.

This week, as friends of mine learned they were now eligible, I received a number of concerned messages. Healthy, careful college students wondered if they should wait so other students who were more at risk could get a shot first. Friends who had already booked appointments wondered whether they were doing the right thing by showing up. Those who are eligible but can not get appointments are angry that lower-risk friends have already received theirs.

There is no question that national vaccine access has been inequitable and that distribution uneven at best. Not everyone who qualifies for a vaccine is able to get one. Americans face difficulty getting to vaccine distribution centers and skeptics still question whether vaccines are safe.

While the desire for orderly and equitable distribution is admirable, the pandemic remains devastating in its scale and impacts. The United States still had an average of 54,000 new cases of COVID-19 last week. We are also staring down more transmissible variants of the virus, increased reopenings, relaxation of restrictions and an unstable economy. It seems that right now holding up doses of the lifesaving vaccine is more unethical than giving it to people who don’t strictly need it the most.

If you are eligible for a vaccination, you should get it, no matter how worthy—or unworthy—you feel. We should not conflate the systemic issues with our healthcare system with our own choices as individuals within the system. Even if you feel it’s unethical that you have been offered a vaccine, that doesn’t mean it’s unethical for you to accept it.

Your choice cannot fix the system

The idea that “my vaccine is being taken from someone else” is a popular phrase in the argument against getting inoculated early. As we’re beginning to find out, that’s not the way our vaccine allocation system is set up. Vaccines are distributed by institutions that don’t have the ability to designate extra doses to specific populations. Despite all the effort that was put into categories and rules, we didn’t anticipate what to do about large-scale refusals, surplus supplies, a slow rollout or about extra doses lying around.

First, there was a power outage in Waterbury, Connecticut on Christmas Day when close to 200 vaccine doses would have been ruined, if health staff had not worked to salvage the doses by vaccinating staff and their families. Then, there was that viral video of Oregon healthcare workers who vaccinated six drivers stuck in their cars during a snowstorm. This impromptu roadside vaccination prevented remaining doses from expiring, even if the recipients did not “qualify” at that moment.

When the choice is between the vaccine ending up in an arm or in the waste bin, the decision seems obvious. Unfortunately, you can’t hold vaccine supply hostage to an ideal distribution system. Our vaccine distribution so far has been erratic, overly political and reflective of a broken healthcare system.

You’re not going to fix the broken system by opting out of it. If anything, you might make the situation worse.

Think about yourself, too.

There’s a delusion of moral purity that guides our desire to refuse vaccination. If you turn down a vaccination based on the belief that you’re not high enough risk, you might also be fooling yourself. It is difficult for all of us to accurately estimate our own risk levels; our own optimistic bias convinces us that public health campaigns are more relevant to others than to themselves.

If your motivation for refusing a vaccine is to support your community, there are ways we can support others that do not sacrifice our own opportunities. As Vanderbilt students, we can volunteer to help drive others to appointments, model safe behavior for younger students and study to help fix our broken healthcare system. As Nashville residents, we can stay away from highly populated areas, wear our masks and be diligent about showing up for testing. As community members, we can help our elderly neighbors and high-risk friends book appointments and show appreciation for healthcare workers and researchers.

Don’t jump the line

Let me be very clear; being deemed eligible for a vaccine is not the same ethically as unfairly taking the initiative to put yourself in front of others. If you are eligible, get your vaccine. If you are not, do not lie to become eligible or leverage wealthy connections. The ethics of early vaccination require that the recipient should not try to influence medical professionals connections or provide bribes or financial compensation. Overplaying a medical condition or placing yourself into a category where you do not belong are not ethical decisions.

It is not okay to seek a way to get vaccinated that involves jumping the line or taking advantage of the system.

Don’t play hero.

Too many of us want to play the expert: “I read an article about this; I watched a YouTube video about this; a friend told me about this!” We spend a good portion of our discussions arguing over who deserves the vaccine more. Even otherwise sensible and well-educated people overestimate their expertise on complicated issues.

Yes, the experts have been wrong and could be wrong, but everybody attempting to play hero on their own is not going to achieve mass vaccination. If the opportunity arises for you to get the vaccine early without cheating the system, you should take it. You are now one fewer person potentially taking up a hospital bed, a ventilator and the time of healthcare workers.

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. If you are eligible for a vaccine, take it.