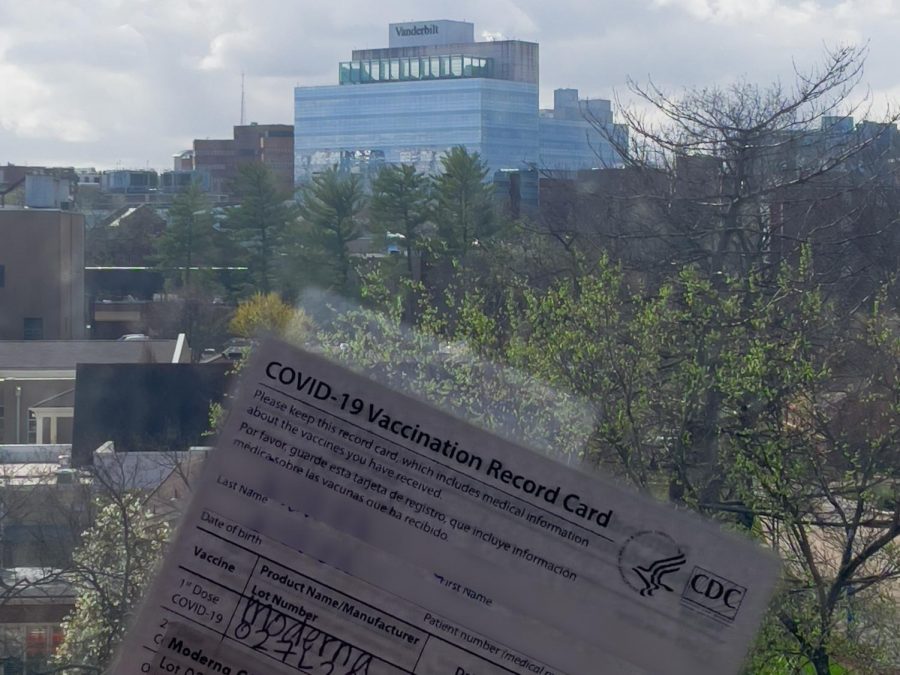

One of the most unique things about Vanderbilt is its world-renowned medical center. Access to top-quality healthcare impacts all of us students. We saw how Vanderbilt’s access helped us in the fall: weekly COVID-19 tests are expensive and hard to come by, and whether or not the COVID-19 policies are a pain, we are privileged to be able to test so often for this life-threatening disease. I am not alone in this reasoning: many students are hopeful that Vanderbilt will again use its connections and esteemed medical center to vaccinate us for COVID-19.

However, in an email to the Vanderbilt community, Chancellor Diermeier stated that Vanderbilt is not eligible to distribute vaccines to undergraduates because the university is not a medical institution. Since the email was sent, the Yale Daily News, the student newspaper, announced on Jan. 15 that the Yale community is estimated to receive the vaccine by April, with student vaccinations possibly occurring shortly after. This prompts the question, why Yale and not us? After all, Vanderbilt issued critically important clinical trial analysis and reporting for the Moderna vaccine. People are criticizing Vanderbilt’s lack of transparency for their vaccine distribution plan.

These times are tough, but we have to be careful about how the vaccine is distributed and ensure that those at high risk are prioritized.

The United States has administered 19,841,721 vaccination doses out of 39,892,400 delivered. These were given to first responder medical workers and just recently began being distributed to the elderly and those with high risk medical conditions. When distributing the vaccine, we need to consider who is in the most danger. Why should we, healthy young adults, be given the vaccine before most elderly people and other high-risk workers? Just because we are fortunate enough to go to a well-funded institution with abundant resources does not make us more deserving than our family members and peers across the nation. Most of us will not see patients in person in the next year. Most of us are in good health. Most of us will have manageable symptoms if we are to catch the virus. We should be more than willing to allow others in greater danger to be vaccinated ahead of us.

Excluding those with medical conditions, the undergraduate student body is not at high risk for infection. Yes, we live in a major city, and yes, we could easily become infected one way or another, but even our highest positivity rate in the fall semester, 1.70 percent, is low enough to make the results of a vaccination dismissable. Of course, this was achieved through strict social distancing policies and quarantining.

I would love to be able to go out into Nashville’s crowded downtown without having to worry about testing positive. I would love to travel over the weekends and breaks. As much as I would love to be having a normal college experience, our low positivity rate is incredible. We are less likely to bring COVID-19 home to our parents and grandparents, who are more likely to have severe symptoms. Since we are, for the most part, isolated together on campus, we do not have an urgent need to get vaccinated. Our older family members, however, have daily jobs—some on the front-lines. They need to be vaccinated before us.

Our lives would be so much easier if we were to be vaccinated. However, in these times, we need to make sacrifices. When my turn comes, I will get the vaccine, but the nurse whose patient is coughing and the grandmother who needs to leave her home to grocery shop should be vaccinated before me.

Vanderbilt Student • Jan 27, 2021 at 11:34 pm CST

I’m sorry but this was very tone deaf. I’m a Vanderbilt student and contracted COVID-19 over winter break since I had to work. Thus, I would appreciate if this person would speak for themselves, as I don’t think their opinion that Vanderbilt students should not receive the vaccine speaks for the student population, nor is this person a doctor who should be decimating medical advice. I have no underlying conditions that I know of but had a nasty experience with COVID, gaining systems like horrible shortness of breath when doing anything, coughing, congestion, and others. I was considered going to the hospital if it got any worse, but I didn’t out of fear that leaving my room could expose my family. I also still struggle to smell and taste several weeks later, and food has been one of my favorite joys: I want to start a restaurant one day. Plus just yesterday, a family friend of mine actually died of COVID-19, so I do not think it’s right for people to spread anti-vaccine sentiments like those expressed in this article. If people are offered the vaccine, they ought to take it and be thankful, rather than conjure up excuses to avoid it. If we had more people vaccinated and were able to inch closer to herd immunity, it’s possible that my family friend’s family could not have been infected and their patriarch could still be here with us to this day. Also, the idea that “we are all isolated on campus” so we don’t need to be vaccinated does not make sense. College students (including at Vanderbilt) are allowed off campus and have become vectors of contagion to the surrounding communities. And even if they weren’t, they could still spread this horrible disease to Vanderbilt staff, faculty, and other students. Lastly, the 1.7% positivity rate cited is misleading, as the entire Vanderbilt in-person student population was tested weekly throughout the fall semester. As such, comparing this rate to those of whole countries, counties, or cities is unfair since those rates don’t include tests of all included people as Vanderbilt’s does. Those rates are likely higher as people with symptoms (not everyone) goes to get tested, meaning they are more likely to have the virus and thus a higher proportion of positive cases would be expected. Additionally, we already have 100 students quarantined and it hasn’t even been a full week since they began to arrive. Imagine if those students all had the virus and went on to spread it to those working in our dining halls, residence halls, and workers and residents of the Nashville community. That wouldn’t be far-fetched, as we did have weeks last semester where the increase in positive cases on campus was over 100. Those are big numbers. In conclusion, I strongly disagree with this article that Vanderbilt students should as a whole turn down vaccinations, for whatever reason.

Drew • Jan 25, 2021 at 8:46 am CST

Awesome Annabelle