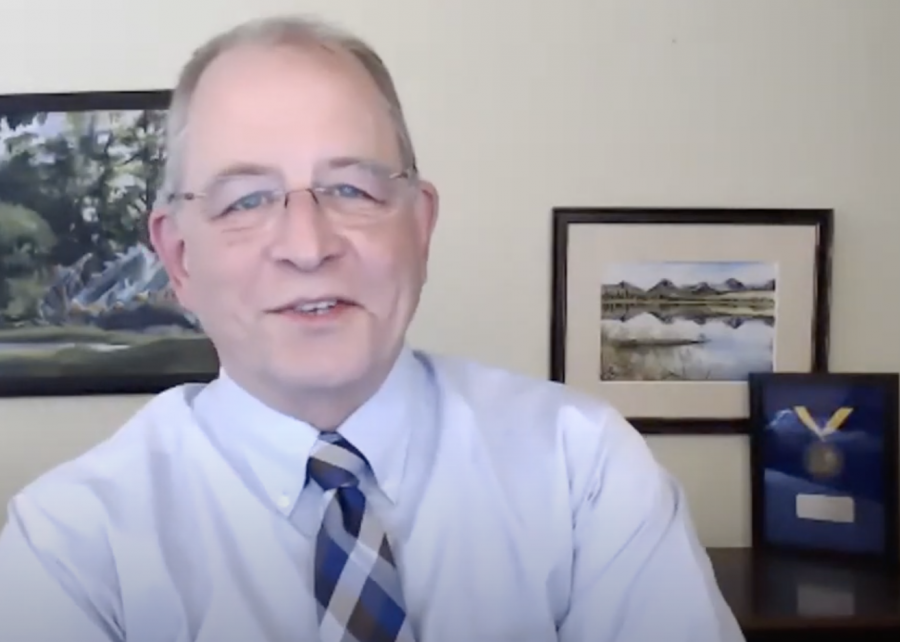

On Monday, Dec. 14, from 11 a.m. to 12 p.m. CST, Chancellor Diermeier hosted an event featuring Dr. Mark Denison. Denison gave a presentation titled “Preparing for the COVID-19 Pandemic… for 36 Years,” discussing the origins of COVID-19, the biology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its context within our society.

Denison is currently the director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He also serves as a professor of immunology, pathology and microbiology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. For over 30 years, the National Institute of Health (NIH) has funded his lab with the objective of gaining a better understanding of the replication, pathogenesis and evolution of the coronavirus class of RNA viruses.

A Q&A session moderated by Taylor Wood, associate Dean of Development at the Vanderbilt School of Medicine & Basic Sciences, followed the presentation.

The Emergence of the Virus

Denison began by admitting how shocking the severity of the virus was to the scientific community. However, he also stated it wasn’t a surprise that it emerged in the first place.

This is due to what Denison termed “the accelerated emergence of zoonotic viruses,” which are animal-based viruses that have the potential or demonstrated ability to affect humans.The oldest variety of coronaviruses—which first emerged sometime between the 13th to 16th centuries—only caused colds. These “simpler” viruses had around 500 to 600 years to gradually evolve and adapt.

Denison provided several reasons as to why the coronavirus emerged in humans. These include the increase of human population, progressive climate change, changing animal habitats and human intrusion into ecological niches and travel.

Denison stated that it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how this coronavirus jumped from animal species to humans. However, he offered a theory.

“Will we discover it? I don’t know,” Denison said. “Where did it come from? It came from a bat. It might have come from a pangolin, but it probably came from a bat. That’s the most closely related, and the probability is it could’ve been multiple ways that it occurred.”

Denison also noted that he does not think the virus is laboratory-engineered. He reasoned that the virus is much too complex to be successfully replicated at this time, and scientists do not have a firm grasp on how the virus can transmit itself across species.

The Denison Lab

From 1984 to 2003, Denison and his lab conducted research on the mouse virus, a representative model of the complexity of the coronavirus. Denison’s team sought to understand several coronavirus complexity, evolution and replication through studying this model virus.

The emergence of SARS (also a part of the family of coronaviruses) in 2003 showed Denison just how profound the effects of modern coronaviruses can be. After this outbreak, Denison’s lab discovered that coronaviruses mutate much slower because they have the ability to “correct” their mistakes in replication. Because of this discovery, Denison is continuing to study drugs that can impede this process.

Denison also applauded his colleagues and other people working in healthcare for their tireless and selfless efforts in battling the devastation of COVID-19. In addition, he also expressed his awe for the speed at which the vaccines and antiviral treatments have been developed and tested.

“We have effective antivirals and treatments within six months, and we have vaccines within nine months,” Denison said. “This is unbelievable, and it’s real; and they’re useful, and we should take them if we can.”

Diving further into COVID-19 medical research, Denison proceeded to discuss the details of a vaccine and the potential of the revolutionary mRNA vaccine—the same vaccine variant manufactured by Pfizer and Moderna.

The COVID-19 Vaccine

As previously reported, Denison himself is an active volunteer for the Moderna trials at Vanderbilt. He has spoken on the protocols put in place to ensure the safety of vaccine clinical trial participants such as regular follow-ups to detect negative side effects or other adverse effects.

“So far, the safety profile [of the mRNA vaccines] have been very good,” Denison said. “The FDA has strict guidelines and requirements for ensuring that a vaccine is both safe and effective.”

According to the data released from Pfizer, the mRNA vaccine has a 95 percent efficacy rate. This means that 95 percent of all cases in trial participants occurred in those who were administered a placebo of saltwater, while only five percent occurred in those who received the actual vaccine.

Denison said that almost everyone should get the vaccine, with the exception of people under 16 years of age, individuals who are allergic to the vaccine’s components or those who have received COVID-19 antibody or plasma therapy 90 days before the vaccine would be administered. Even individuals who were already diagnosed with COVID-19 should receive the vaccine, Denison said. This is due to the potentially more sophisticated immunity offered by the vaccine.

Denison noted that “if you are under 16, because it’s not in the EUA (emergency use authorization), it’s not been tested [in children]. We do see much less severe [symptoms] under the age of 16, but it’s an artificial number. Children can still get seriously ill from [COVID-19], and we worry about kids who may be immunocompromised.”

Although Denison stated that there is no way to know how long immunity may last, he also emphasized that individuals should get both doses of the vaccine. For the Pfizer vaccine, individuals should be administered the second dose 20 days after the first. For the Moderna vaccine, individuals should be administered the second dose 27 days after the first vaccine. Individuals are not considered entirely protected until one week after the second dose is administered.

Denison stated that it is common to experience side effects after vaccination which may include sore arms, fatigue, muscle aches, fever and headache. These symptoms, he added, are more likely to occur after the second dose than after the first. He considers feeling these symptoms to be a good thing as they confirm that the vaccine is working to help the body build an immune defense.

However, there are symptoms that the vaccine should not engender. These include hives, shortness of breath, difficulty swallowing, cough and loss of olfactory senses. If one feels symptoms such as these, Denison said, one should consult with their health care provider. Furthermore, symptoms should only be proximal, lasting around one to two days.

Importantly, Denison stresses that COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are still in their infancy, which is why find a way to say this without going into second person please

In the meantime, Denison encourages everyone to continue to wear masks and social distance. , taken Dec

“Can I stop wearing a mask after I get vaccinated? No, you can’t. You cannot,” Denison said. “We know that the vaccine reduces or prevents symptoms. We hope it blocks infection and transmission, but we do not know that.”