“What school do you go to?”

Before transferring to Vanderbilt University, I would enthusiastically respond “San Francisco State University” only to be met with disappointment from the once piqued minds. In my hometown of San Francisco, attending an elite university was socioeconomic capital exclusive to the wealthy. The neglect of students at SFSU didn’t go unnoticed, especially when peers at neighboring elite undergraduate institutions like Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley were seizing exclusive research opportunities I could only hope to get. Proving my worth became an insurmountable task when students at elite institutions were seen as infinitely more valuable with a renowned university on the header of their resume.

Though elite universities like Vanderbilt allow their students to be hailed as future leaders simply by association, the cost of attending such institutions is sometimes prohibitive, leaving students stunned as they ponder how their families will weather the impending financial burden. For the 2020-2021 academic year, students living on-campus are expected to pay up to an estimated $75,974 for tuition, housing, meals and more.

Abrupt halts in familial income due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and students opting for remote learning have failed to convince the Vanderbilt administration to lower tuition rates—all students will be billed $52,780 for the upcoming school year. While Vanderbilt offers financial aid, many feel that it’s still not enough to supplement the impact financial losses COVID-19-related closures caused. Current financial aid profiles, which are largely based on 2018-2019 tax returns, may not reflect these financial losses and potential return flights needed if Vandy sends students home mid-semester, resulting in significant proportions of the student body calling for more relief. Hence, many must quickly decide whether the historic Vanderbilt name, its prestige and the semi to fully-remote learning style are worth the hefty price tag.

After being accepted to Vanderbilt, I was finally proud to tell curious peers where I would complete my undergraduate degree. Alumni and Vandy fans noticed the Vanderbilt hoodie I proudly wore as I strolled along Market Street, San Francisco. I was part of an exclusive club that could propel my scientific career. A wave of relief came over me as I realized I wouldn’t have to go above and beyond to prove that I was comparable to undergraduates at other elite universities.

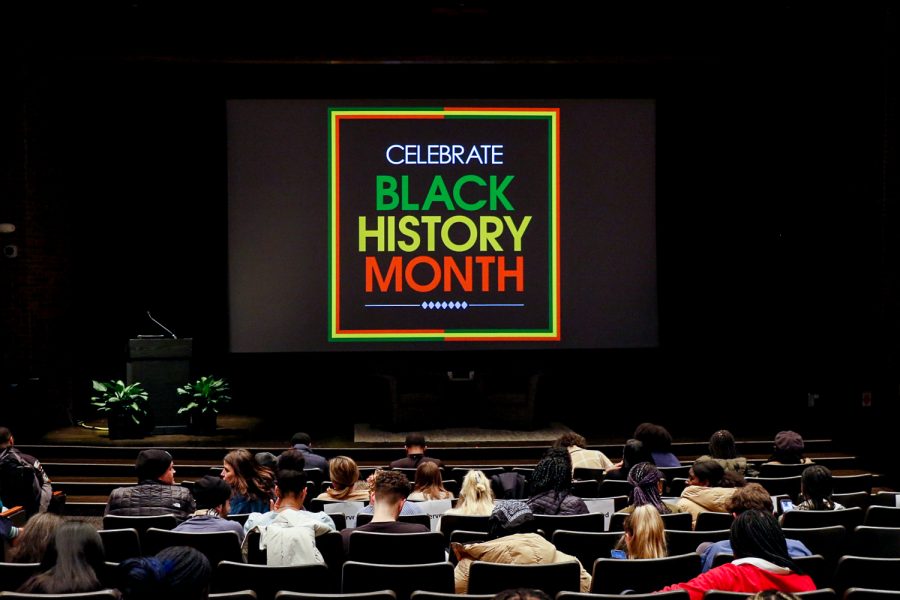

Critics of college prestige cite a Princeton University study that found no significant difference between high-achieving students at elite versus often cheaper, non-elite schools. Regardless of further studies touting the insignificance of prestige on employment and salary, going to an elite school will have a greater impact on the lives of minorities. As a low-income student, the jump from a non-elite to elite school revived the fabled American Dream. Further findings from the Princeton study indicated that “black and Hispanic students” and “students whose parents have relatively little education” benefited greatly from the connections and positions nepotism couldn’t secure.

Additionally, an analysis from the Alliance College-Ready Public Schools states that selective universities do a better job of graduating marginalized students promptly compared to their non-selective counterparts. Amongst SFSU’s class of 2019, internal research indicates that only 23.1 and 55.8 percent of students entering as freshmen graduated in four and six years respectively. So, while non-elite schools like SFSU see impressive diversity statistics, they disservice a significant proportion of these underserved communities, forcing them to leave without a degree or pay out-of-pocket after financial aid expires. Vanderbilt, which boasts 88 and 93 percent four and six year graduation rates respectively, grants disadvantaged students a greater chance of obtaining a bachelor’s degree. However, high admissions standards at elite schools favor wealthier students who can afford counselors that will ensure perfect profiles. The appeal to wealthier students is most prominent at Vanderbilt, which comprises the greatest proportion of students from the one percent among all elite colleges.

On July 21, Vanessa Martínez, a journalist at the Los Angeles Times, tweeted that only 10 out of 250 fellow and intern positions at the LA Times went to students from California State Universities, a consortium of public schools that hosts the greatest amount of students in California that is often viewed as second-class compared to the renowned University of California system. Because the LA Times is based in Los Angeles, some suspect that favoritism from recruiters led them to hone in on elite schools in the area, like the University of Southern California and UCLA, rather than non-elite ones like CSULA. A LA Times journalist doubts her chances at securing her current position had she graduated from a CSU instead of USC in a recent tweet. Though the selection process is veiled in mystery, in a letter penned by CSU Northridge professors, faculty hypothesized that CSU journalism programs may be seen as lesser than those of prestigious universities due to the latter being “better-resourced,” resulting in bias favoring students from the elite schools via alleged constant recruiter presence.

The prejudice exhibited by the LA Times against the CSU system is discriminatory towards Latino students, who comprise 43 percent of the CSU’s students, per Martínez. Moreover, other Latino journalists at the LA Times cite poor Latino diversity statistics amongst the LA Times’ managing and editing teams that do not reflect those of California, a state where approximately one in two residents is Latino. Of course, intersections between race and other sectors of oppression like income inequality force disparities like those exhibited by the LA Times down a multifaceted spiral. Simply put, an attack on the Latinx community is also an attack on all intersecting marginalized groups.

Even if minority students are recruited from other non-elite schools, the cost of schools amongst the CSU system—which are by far the cheapest non-profit schools in California—attracts low-income students of all intersecting disadvantaged backgrounds. In fact, the UC consortium and neighboring private schools have tuition sticker prices at twice to seven times those amongst CSUs. Despite generous financial aid packages that may cover tuition, these competing schools inevitably attract a significant amount of relatively well-off students whose families can fund other college-related expenses like housing costs. For some, the larger CSU system, composed of many commuter schools, offers students an economically-wise balance between going to college and paying less via the absence of housing costs. So, any dismissal of CSU students will still result in discrimination of disadvantaged students on the basis of income, which intersects with disadvantaged racial and gender groups, among others.

This case isn’t unique to the LA Times: similar practices occur in other places like elite law firms, where most students from less prestigious schools are filtered out. Such cases highlight the unfair—but indispensable—privilege marginalized folks can only find in elite undergraduate institutions.

Instances like these display the consequences of not having a degree from an elite school. If a degree from Vanderbilt or any other elite institution greatly advantages students via access to job opportunities, the name must hold some value. However, many students still question whether the valuation of elite degrees at a sticker price of approximately $300,000 is just.

Most classes at Vandy are adopting a fully-online or hybrid model for the Fall 2020 semester, pushing students to call for reduced tuition due to an inevitable drop in educational quality. In short, Vanderbilt’s professors aren’t trained online-only teachers and may not use online mediums to teach effectively.

As Vanderbilt refuses to reduce fees or promise on-campus housing refunds if students are forced to return home, many must decide whether transferring to a cheaper school or taking a gap year are better alternatives than being billed the full cost of an in-person education for online education.

Many low-income and middle-class families are declaring unemployment due to the ongoing pandemic, undergoing unexpected and enormous financial stress. Universities that fail to subsidize fees, despite knowing that the fall collegiate experience will be of vastly lower quality than usual, disproportionately hurt families with little capital to weather the lingering pandemic.

Disadvantaged students will see a sharper drop in quality as any plans to integrate them into elite college life take place virtually or get canceled altogether. First-generation students’ unfamiliarity with college life calls for academic institutions to establish networks to smoothly transition them into college. Unfortunately, many networks rely on regular face-to-face communication that systems like online roommates cannot supplement. Furthermore, such disadvantaged students will have a harder time adapting to rigorous curriculums, as their history of underfunded educational experiences likely hindered their ability to indulge in Advanced Placement and honors courses in high school. Inevitably, many students—especially those from underserved communities—will seek tutoring to supplement their lack of knowledge in certain classes. In addition, job and club fairs held throughout the semester, but especially in the beginning of each semester, provide meaningful opportunities for disadvantaged students to learn outside the classroom that they would normally not be able to access. Vanderbilt must carefully plan virtual and in-person tutoring sessions and job/club fairs to ensure student success, especially if students are unexpectedly forced off campus mid-semester due to COVID-19, or risk the academic failure of their student body.

For disadvantaged students, the worth of an elite degree goes beyond cost. With the ongoing pandemic, they must quickly determine whether easier access to jobs and a world-renowned name can compensate for possible culture shock, hyper-elitism and unexpected financial burden. As disadvantaged students seek financial relief to help their families weather sudden losses in income due to COVID-19, Vanderbilt must provide them with further supplemental resources necessary to make campus a second home. Increasing Opportunity VU grants, refunding tuition if students are forced to return home and compensating students for unexpected travel expenses can drastically reduce the gaps in elite college experience between marginalized and privileged students. All must do their part to ensure that disadvantaged students have an equal chance at obtaining a valuable college experience, degree and job. In the meantime, admissions teams at elite universities must make a top-tier educational experience—especially virtual ones—more equitable to ensure that a diverse array of students can reap the benefits of their flashy name.