War hero, Congressman, president and patriot George Herbert Walker Bush died on the last day of November in his home in Houston, Texas. Battling Parkinson’s, frailty and the recent passing of his wife Barbara, he died at the ripe old age of 94. He will be remembered as the last of his kind: a moderate leader who prioritized compromise and sound policymaking over pure ideology. We should extol him for his military service, his attempts to navigate an increasingly polarized Washington and his ability to make friends of seeming political enemies.

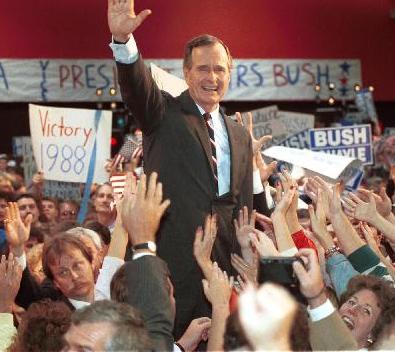

Visiting Distinguished Professor at Vanderbilt and Pulitzer-Prize winning historian Jon Meacham thinks we should extol him for other things. Having served as the late president’s biographer, he spoke at Barbara Bush’s funeral in April and delivered a eulogy for Mr. Bush. Additionally, he published an opinion article for the New York Times entitled, “George H.W. Bush and the Price of Politics.” He details Bush’s patriotism, his disorientation among a changing political landscape and his penchant for compromise and deal making – all of which is fine. However, one of Meacham’s key points was that Bush was so devoted to this nation and confident in his ability to lead that he was willing to play political hardball in order to attain the highest of leadership posts: the presidency.

George H. W. Bush ran a deeply racist campaign that leveraged implicit prejudices in order to gain votes.

I do not question Meacham’s assessment of Bush’s love for country and reluctance to use hardball politics. He became one of the youngest fighter-pilots in American history and earned the ire of the more uproarious, conservative wing of his party. This much is true. But to applaud Mr. Bush for his 1988 presidential campaign is flippant and racially insensitive.

George H. W. Bush ran a deeply racist campaign that leveraged implicit prejudices in order to gain votes. Meacham acknowledges that Bush was “hard-knuckled” during this campaign. But that doesn’t capture the damage that his campaign did. This is often epitomized in the notorious “Willie Horton” ad, in which a cold narrator skewers Bush’s opponent, Democratic Governor of Massachusetts Mike Dukakis, for his record on crime. The narrator tells the viewers about the case of Willie Horton, who received furloughs (temporary release) from prison after being convicted of murder. During one furlough, Horton kidnapped a man and woman, stabbing the man and raping the woman.

This ad is a textbook “dog whistle,” or implicit appeal to racism. The ad depicts Horton, a black man, only in mugshots and handcuffs. He has unkempt hair and a scraggly beard. He epitomizes the eternal white fear of black violence: the hypermasculine black criminal fiending to rape white women and kill white men. This tactic split the electorate: by percentage, Bush received both more white votes and fewer black votes than Ronald Reagan did in 1980. Additionally, while on his deathbed, Lee Atwater, who ran Bush’s 1988 campaign and passed away less than two years after the election, explicitly apologized for the racist Willie Horton ad and other harmful tactics used against Dukakis.

We are still living with the legacy of Willie Horton. Dog whistle campaign ads are abundant: Donald Trump aired an ad that, under the guise of promoting border security, juxtaposed masses of invading, cop-killing Hispanic migrants to idyllic white women in an attempt to shore up white Republican support before the 2018 midterms. Bush set the precedent for this racist fear mongering. It would be Machiavellian to celebrate him for it.

Meacham attempts to tell the whole truth while absolving Bush of sin.

There are roughly two schools of thought when it comes to speaking of the dead. One argues that criticizing the dead for their faults only hurts those who were close to the deceased. Further, the dead cannot defend themselves from this criticism, so attacking them creates a one-sided argument. The other school argues that telling the whole truth is virtuous irrespective of timing. People, especially young people, will use the words spoken about the recently dead to build much of their mental archetype of deceased. My classmates were not alive to evaluate Bush when he was politically salient – the time we are taking now to develop a painting of his legacy will be formative in determining how this painting looks. Therefore, we need to be truthful about both Bush’s virtues and sins in order to paint an accurate picture.

Meacham splits the two: he attempts to tell the whole truth while absolving Bush of sin. He incorporates one of Bush’s darkest moments, his divisive 1988 campaign, and strips it of its substance. He incorporates the bloody heirloom of American racism into Bush’s determination to serve his country: Bush was so dedicated to leading this nation that he was willing to cause harm in order to get in a position of power.

George Herbert Walker Bush was a great man. He sacrificed. He governed admirably. He cared deeply about the United States of America. But he was a flawed man, as all people are. Bush was willing to use racism as a means to an end. We should recognize him as a great man in spite of this, not because of it.

Max Schulman is a sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences. He can be reached at maxwell.r.schulman@vanderbilt.edu.

Common Sense • Dec 7, 2018 at 8:34 am CST

You’re either ignorant or a liar, not knowing that the Horton ad was made by a Super Pac, not Bush’s campaign.

“He was willing to cause harm to gain power.” That would be like blaming John Kerry for Dan Rather lying about W’s service. Sure, they came from the same side of the aisle, but this is an attack on 41’s character.

Also Meacham does not at any point laud “his” racism, so the entire headline is bogus.

You enjoy wearing Obama themed apparel? Damn you must be lauding the Fast and Furious Scandal. You must be celebrating that he weaponized the IRS. You must endorse that he smiles with Farrakhan. You must be thankful that he secretly agreed to let hezbollah off the hook.

Terrible headline, misleading information, all around a bogus premise.

Howard C Ellis • Dec 6, 2018 at 8:53 pm CST

The only “racism” you pin on George H.W. Bush is the Willie Horton ad. Some questions:

Was Horton a murderer? Did Dukakis give him a furlough during which he raped a woman and committed an armed robbery and assault? Was he black?

Dukakis was notoriously weak on crime. During a televised debate he was famously unable to answer a question about what punishment he would want to be imposed on a man who (hypothetically) raped and killed his wife.

It wasn’t Horton’s blackness that was the salient feature of this line of attack. It was his criminality. He was the one murderer that Dukakis furloughed that committed serious crimes while on that furlough. Was Bush supposed to white-wash (no pun intended) his race, or was he supposed to avoid mentioning the case at all?