A response to Acceptance Is A Two-Way Street

I’m a 21-year-old lesbian who’s a semester away from getting her diploma at Vanderbilt University. I still haven’t come out to the vast majority of my family, some of my friends or most of my acquaintances. Those who are lucky enough to know have greeted me with open arms, casual indifference or open hostility and disgust. Coming out has been a lengthy and arduous process because there’s no way of knowing which reaction I’m going to get.

It’s easy to theorize that homophobic people will change their stripes once confronted with the reality that yes, someone they know is gay. Within the LGBTQ community we are all unique individuals, despite decades of propaganda painting us universally as perverts, predators and social deviants. It’d be a natural, if idealistic, hope that some sort of social exposure would cause an individual to stand out and suddenly humanize the entire group as anything other than a monolith.

However, bigotry just doesn’t work that way. Except in a minority of cases, the acceptance (or assimilation) of a member of a marginalized group results in that member being coded as an outlier. If your friends and family were using homophobic slurs and openly hating gay people before you came out, it’s almost guaranteed that they are still doing those things. Just not around you, because you’re different and they don’t want to offend you specifically.

The choice to meet homophobes halfway (or any kind of bigot, really) and ‘accept’ their degrading and dehumanizing views as somehow equivalent in value to a marginalized people’s push for survival represents one half of a rock-and-a-hard-place dilemma. Do you become complicit in the validation of a harmful and violent system of beliefs (and potentially face less open discrimination from the majority), or do you assert your own humanity and that of others (but alienate those who don’t want to move beyond individualized tolerance)?

The decision to simply accept bigotry and ingratiate yourself to an oppressive system when you could do otherwise speaks to immense privilege in other areas of life. I have close friends who have been kicked out of their homes, physically or sexually abused, or otherwise harmed when they tried to come out to homophobic parents and friends ‘respectfully.’ One friend attempted the whole “I want to respect your views and accept you if you’ll accept me” schtick with their parents and it didn’t stop the drive to a conversion therapy camp in Denver. Approaching with an olive branch made of respectability politics didn’t help a girl whose father said he’d rather see her dead than married to a woman. My own admission of non-heterosexuality, intended to be an act of emotional intimacy between friends, was taken as a challenge by the boy who proceeded to violently assault me. Anecdotes not communicating the very real danger still faced by LGBTQ people today? Try statistics:

40% of homeless youth identify as LGBT, with the majority of them citing their identity as a major contributing factor in their homelessness.

Approximately 1 in 4 LGBT employees experienced homophobic or transphobic discrimination in their workplaces within the last 5 years, negatively impacting overall health and well-being. 30% of transgender individuals reported being fired or denied a promotion because they were out as transgender at work.

Living within even a passively homophobic environment (such as one where the child agrees to never emphasize or act upon their identity in exchange for familial acceptance) carries with it heavily increased risks for psychological damage, substance abuse, and suicide.

Acceptance of LGBT people has actually been declining among Americans in recent years.

The ideology backing and enabling homophobes is not as simple as distaste with our ‘lifestyle’ (and for the record, an immutable and unchangeable identity is not a lifestyle. I can’t believe I’m typing this in 2018). Homophobia, like transphobia, racism, etc., is a result of a grander, oppressive institution. An institution which, if operating perfectly, would see the total subjugation or extermination of minority groups. I, and others like me, are not required to adapt to this institution or prove that we are somehow worthy of existing under it with the barest degree of dignity. When ‘genuine belief’ translates to a systemic denial of humanity or the condoning of violence, abuse and exploitation it is no longer ‘just an opinion.’

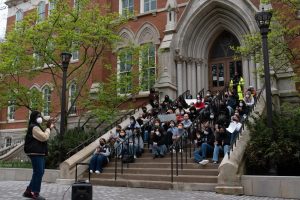

The paradox of respectability politics, the aforementioned servility to institutional oppression, is that focusing our efforts on convincing the individuals around us of our humanity will result in no long-term change. There are not enough of us to talk to every single homophobic person, and a significant portion of homophobes hate us enough to cause us actual interpersonal harm. It is a dangerous, impractical and impermanent option. This is why community mobilization is so incredibly important to marginalized groups. And, as in any mass movement against a dominant culture of bigotry, resistance is expected. The path to liberation, equality, and acceptance is not paved through placing responsibility on individual shoulders but through engendering an actual culture shift through policy, communal support and social advocacy

The whole point of a movement for acceptance is that it disrupts the ingrained conception of what is acceptable. You cannot call the acceptance of prejudice and the acceptance of basic humanity an equal exchange. That two-way street was not paved with us in mind.