Updated July 31, 2018 at 1:01 p.m.

Content warning: Racist slur

On Monday evening, a number of Vanderbilt students received an email inviting them to subscribe to a racist, white supremacist listserv. The message did not go out to all students, and appears to be targeted to members of National Pan-Hellenic Council organizations–historically Black Greek letter organizations–according to senior Brianna Mayo, who started a Twitter thread about the email. Members of Vanderbilt’s National Panhellenic Conference, Interfraternity Council and Multicultural Leadership Council also reported receiving the email. According to Dean of Students Mark Bandas, the email went out to a far broader range of faculty, staff and students.

Vanderbilt University administrators, as well as VUIT and VUPD, are currently investigating the source of the message.

When the Hustler reached out to VUPD’s non-emergency hotline for additional information Monday night, responding officers were not aware of the situation and consequently asked the Hustler to file a report.

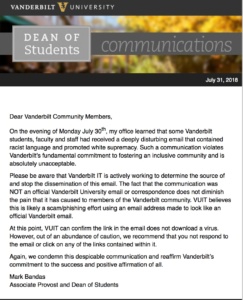

In an official statement sent out to students in the early morning hours on Tuesday, Bandas said that VUIT is currently working to find the source of the email and believes that it is likely a scam/phishing email as opposed to an official Vanderbilt email. A message from Provost Susan Wente and Tina Smith, Interim Vice Chancellor for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, was posted on Tuesday morning, calling the message “abhorrent and antithetical to our values as a university community.” The message said they believe the email was an external attack made to look like an official Vanderbilt email.

VUIT confirmed in the statement that the link in the email does not download a virus; students are, however, still cautioned against clicking any links in the email or responding to it.

Mayo said that while she was curious about the nature and source of the email, she “wasn’t shocked in the slightest” and believed that it was “only a matter of time” before the school’s Black community faced an incident like this one.

Many affected students reached out to administrators and began conversations about the message on social media. Mayo said that much of the conversation among Vanderbilt’s Black students has been on next steps about how to address the message and how the university needs to respond to the incident. Regardless of whether the email was a scam, Mayo said, the incident is indicative of a culture of racism that surrounds the university, one that she says the university needs to take responsibility for.

“The fact of the matter is that one way or another those were sent to Vanderbilt emails, to a specific community within Vanderbilt,” Mayo said. “This was a targeted attack by someone with access, which indicates it is someone at Vanderbilt, student or otherwise. We all hope the administration takes action accordingly, but I’m worried they’ll just continue to attribute it to a random virus.”

The white nationalist email blast that was sent out to many Black Students tonight is yet ANOTHER reprehensible display of how racism and hatred is ingrained into Vanderbilt culture pic.twitter.com/BYJnFncRyc

— Vanderbilt NAACP (@VandyNAACP) July 31, 2018

For Mayo, the situation is reminiscent of an incident last year in which white supremacist flyers were found on campus. The university responded to the incident over a week after the flyers were found, saying that the flyers violated the University’s Publicity, Promotions, and Advertising policies and were removed.

“The same culture that allows someone to send these emails, to post those flyers, to give Milo Yiannopoulos a platform, to allow shit on the steps of the BCC, is also the one that allows people to never take an [African American Diaspora Studies] class, to never take a class taught by a professor of color, etc.,” Mayo said. “So many Black students have spoken of being in Visions with white peers, only to be ignored by them outside of that hour long session once a week for a few months. It all stems from the same thing.”

Bandas wrote in his official statement that the message in the email violates Vanderbilt’s commitment to inclusion and is “absolutely unacceptable.” He condemned the email as despicable.

“The fact that the communication was NOT an official Vanderbilt University email or correspondence does not diminish the pain that it has caused,” Bandas said in the statement.

To Mayo, however, his message seemed lackluster, and she worries that the administration will believe that the one email message was sufficient and move on quickly, which she views as problematic.

“As far as the email we just received [from Dean Bandas], two parts stuck out to me. ‘Some Vanderbilt students, faculty and staff.’ It would mean so much more if they said who. ‘Some’ makes it seem random, and it was not at all random. And second, ‘…reaffirm Vanderbilt’s commitment to the success and positive affirmation of all.’ I personally have not seen this so-called commitment. Commitment to who? What is that commitment? Again, what steps is Vanderbilt actually taking to positively affirm all members of its community? How can anyone who is not a white male at this school focus on their success when they have to constantly worry about things like this?”

Going forward, Mayo believes that several email messages from administration are necessary in a situation like this: one sent out almost immediately to alert students of the situation and reassure them that investigation will follow, recognizing the racism present on campus and work Vanderbilt must still do to absolve it, a second email sent out in which consequences are outlined, and a third that outlines next steps.

“Where does Vanderbilt go from here? How do we move on as a community? How do we welcome over 160 Black freshman, and many more freshmen of color, abilities, sexualities, gender identities, etc,” Mayo questioned.

Mayo continued by pointing out that in addition to communication, she and other people of color on campus are looking for specific actions to curtail hateful acts like this one and to hold the perpetrators responsible.

“We need an investigation. We need communication with the entire student body explaining exactly what happened, who was targeted, and, most importantly, how it was able to happen,” she said. “We need an acknowledgement of Vanderbilt’s racist culture that allows for things like this to occur. We need an explanation for how Vanderbilt’s past responses have created an environment in which people feel like they can do and say these things and get away with it. We need names of those responsible and their consequences. We want firings and we want expulsions. And finally, as Black students we need an actual plan for recourse. We don’t want to hear about the PCC and CSW and town halls and ‘resources to cope.’ We are tired of this fake care. At the end of the day, this makes Vanderbilt an unsafe community and we need to see tangible measures to rectify that.”

Jacob Pierce, president of the Vanderbilt Multicultural Leadership Council said that incidents like this are part of a larger political climate that leaves marginalized communities feeling undervalued. He and other leaders in the MLC are looking into ways they can remind their partner organizations of their value to the campus and let everyone know that messages like the one contained in the email are unacceptable in the university community.

“The university’s investigation cannot erase the fact that we are living in a political climate that is hostile to minorities. Countries are denigrated as shitholes, migrant children are being locked in cages and the President of the United States stokes racial tensions by attacking black athletes for demanding this country live up to its founding promise and treat all citizens equally. In this political climate, we all have an obligation to make sure that the people with historically marginalized identities feel seen, valued and heard.”

The Hustler will update this story with additional information as we learn more.