Content warning: sexual assault and interpersonal violence

The article you are about to read is the story of my experience as a survivor of sexual assault and a frank retelling of the problems and frustrations I dealt with while pursuing an investigation through the Title IX office. I feel that my story is important, as it shows that Vanderbilt’s handling of sexual assault cases is not what it needs to be. This investigation has caused sleepless nights, many tears and vulnerability like I have never before experienced. However, I would go through it all again. I hope that reading my story shows that while Title IX investigations are painful, they can bring closure and relief to the survivor. This investigation has opened my eyes to the wonderful people at Project Safe, who guided me through this process and gave me the support I needed to keep pursuing this investigation.

I would like to thank the entire Hustler staff, in particular Sarah Friedman, who not only listened to my story, but also gave me the opportunity to reclaim my story through this article. For six months I have felt as though what happened to me was a secret. I felt that no one, particularly Vanderbilt administration, cared about the trauma I had been through. By agreeing to interview me and publish this article, The Hustler has shown me that people do care, and that my story matters.

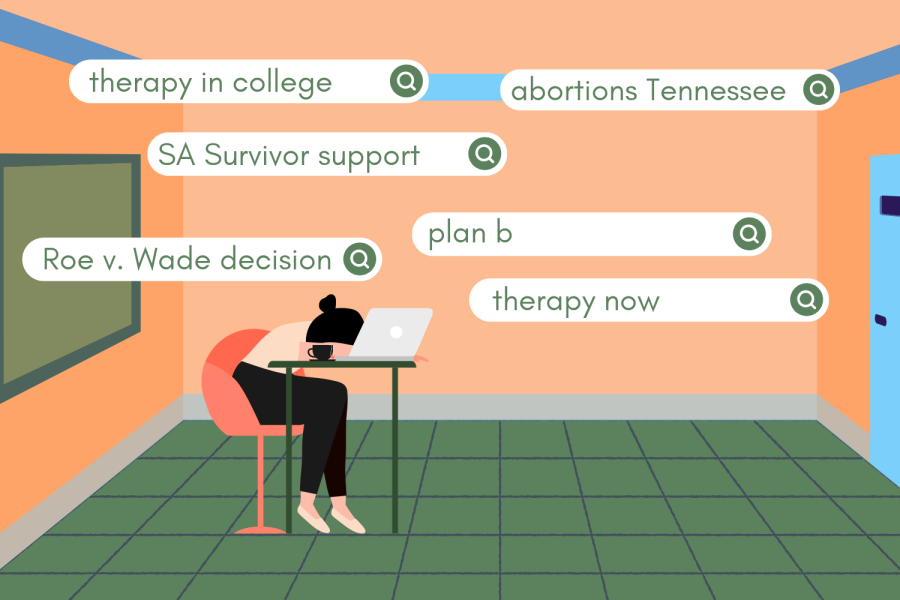

I also want to explain why I have chosen to remain anonymous. Originally, I was adamant that I wanted my name included, because I felt that the Vanderbilt community would be more likely to care about this article if they could put a face with the story. However, the internet is forever. I did not want this article to be the first thing that appears in a simple Google search of my name. I do not remain anonymous because I am ashamed or afraid. I remain anonymous because I do not want my assault to be the first thing people know about me, as I am so much more than that.

Sincerely,

Rachel*

*Editor’s Note: names have been changed.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Rachel* said she met Joe* at an off campus party one Friday night in September. Later that night, Rachel said she took an Uber with Joe back to his dorm room. Upon arriving at Joe’s dorm, Rachel said she agreed to have sex with him as long as he used a condom. She said she saw him grab one, and that the two engaged in sexual intercourse. However, when she turned her head, she said she saw the unwrapped condom lying next to her on the pillow.

“So I pushed him off of me,” Rachel said. “We had an argument in which he said ‘I don’t see why it’s a big deal.’ And I said, ‘It’s a big deal because I said I would only have sex with you if you wore one.’ And so I just threw my clothes on and ran out of that room.”

On her way out of Joe’s dorm building, Rachel said a VUceptor who she knows helped her call the the 24-hour crisis and support hotline monitored by Project Safe, Vanderbilt’s Center for Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response. Otis McGresham, a Project Safe Prevention Educator and Victim Resource Specialist, answered the call, and Rachel told him about what happened with Joe. After a brief conversation with McGresham, Rachel decided that she would go to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) to get a forensic examination done by a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) nurse.

McGresham met Rachel at VUMC when she arrived around midnight, and he remained by her side throughout the night. Around 45 minutes after arriving at VUMC, Rachel spoke with two detectives, one from Vanderbilt University Police Department (VUPD) and the other from the Metro Nashville Police Department (MNPD). McGresham wasn’t allowed to speak to the detectives, but he remained with Rachel as she answered their questions.

The MNPD detective, who Rachel described as “dismissive,” did most of the talking, Rachel said.

Otis McGresham, a Project Safe Prevention Educator and Victim Resource Specialist, answered Rachel’s call to the center’s 24-hour hotline.

“As soon as he walked in, I got this feeling he wasn’t going to believe me,” she said. “He just kind of looked suspicious of me the whole time. He was cranky, and he just kept looking at the door like he was waiting to see when he could leave.”

The MNPD detective concluded that because Rachel agreed to have sex with Joe, no crime had occurred, and he didn’t fill out a report, Rachel said. Vanderbilt’s detective informed Rachel that Vanderbilt would be looking into the incident. Chapter seven of Vanderbilt’s Student Handbook, entitled “Sexual Misconduct and Intimate Partner Violence,” states that effective consent “requires mutual understanding and agreement regarding the use and/or method of prophylaxis and contraception.”

After her conversations with the detectives, Rachel waited an hour for SANE nurses to arrive to complete the forensic exam, she said. VUMC has a contract with Nashville General Hospital to provide SANE services, said John Howser, a spokesperson for VUMC. In accordance with this contract, Nashville General Hospital sends the practitioners when VUMC requests them.

“I had to wait an hour for them to come,” Rachel said. “I wasn’t allowed to drink anything, pee… I just had to sit there. I couldn’t change my clothes.”

According to Howser, VUMC has been preparing to offer SANE services in the Emergency Department and in the Student Health Center for several months. These preparations have included clinical preparation, training, equipment and supplies purchasing and development of operating procedures among other details, Howser said.

“We are pending full stakeholder approval but intend to launch these services soon,” Howser said.

Furthermore, representatives from the Metro Nashville Health Department, hospitals (including VUMC) and others are working to create a broader network of resources to assist sexual assault victims, Howser said.

“It’s hard to explain how you feel after you’re assaulted, because it’s almost like time is kind of frozen and it’s really hard to believe that it happened to you. It doesn’t feel real, but it is.”

After leaving the hospital around 4 a.m., Rachel spent the remainder of the weekend trying not to dwell on the incident.

“On Sunday, I wanted to go back to school. I wanted to get back into my routine,” she said.

“It’s hard to explain how you feel after you’re assaulted, because it’s almost like time is kind of frozen and it’s really hard to believe that it happened to you. It doesn’t feel real, but it is.”

Rachel met with McGresham at Project Safe a few days later, and he walked her through what the reporting process would look like.

“He’s the only one that ever explained anything to me,” Rachel said.

McGresham also told Rachel about the resources that Project Safe could provide, including extensions on class assignments and exams, housing relocation, a student-requested leave of absence and a stay-away order, but she didn’t opt to utilize them. While Rachel was afraid of seeing Joe around campus, she didn’t want to get a stay-away order, she said.

According to Mary Helen Solomon, the Director of the Office of Student Accountability, Community Standards and Academic Integrity a stay away order is “a mutual directive between students” which instructs students to avoid direct or indirect contact with each other in person and over the phone and social media. If students end up in the same place, they are expected to avoid “any and all unnecessary conversation or contact,” Solomon said. In some cases, Student Accountability may issue additional interim measures, such as prohibition from a particular building. Alleged violations of stay away orders are addressed “through the usual student accountability procedures,” Solomon said.

“I didn’t get a stay away order because I felt like he had already taken so much control away from me,” Rachel said. “I didn’t want to spend my time worrying about what if I go somewhere and he’s there and I have to leave because his presence dictates where I can and can’t be.”

Because VUCeptors are mandatory reporters, the person who helped Rachel call Project Safe was required to report the incident, which kickstarted Vanderbilt’s investigation. While the investigation had been opened up with Equal Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and Disability Services (EAD), Rachel was not required to participate. She said she chose to participate because McGresham told her that the case against Joe wouldn’t be as strong if she didn’t.

“It made me feel right away like I am not important to them. That feeling has continued.”

“I wanted him to be held accountable,” Rachel said. “The thing that made me the angriest was when he said ‘I don’t see why it’s a big deal.’ Because he made the choice to expose me to pregnancy or an STD, even HIV. He took that away from me. There are these posters all over campus that talk about effective consent, and that was just taken away from me. I felt like I had done everything you’re told you’re ‘supposed’ to do. I was very clear about my expectations. There was no ambiguity about whether or not he had to use one.”

Rachel said she received an email from an EAD investigator, who informed Rachel that she was assigned to her case but would be out of town and couldn’t discuss the investigation for another eight days.

“I didn’t understand why I couldn’t talk to someone else, because [eight days] is a long time to make someone wait to talk,” Rachel said. “It made me feel right away like I am not important to them. That feeling has continued.”

Rachel went to EAD for her preliminary interview on Oct. 19. During the meeting, she said she felt as though the two investigators were looking at her like a zoo animal, not making eye contact with her and making her feel “suffocated” in the small meeting room. Their faces were blank, and their voices were monotone, Rachel recalled.

“It was like talking to two robots,” Rachel said. “Just no emotion from either of them. And I understand that they don’t take sides, but [I would have liked] to at least feel some empathy from them. It was weirdly emotionless.”

Molly Zlock, Director of Title IX and Student Discrimination, said that the Title IX Office strives to create a comfortable atmosphere for both the complainant and respondent during investigations. As part of this effort, the office permits both parties to be accompanied by an advisor during any meetings and interviews. According to the Student Handbook, the advisor “may confer privately with that party, but the adviser may not speak on behalf of the complainant or respondent or otherwise participate in any meeting.” McGresham served as Rachel’s advisor for all of her interviews and meetings with the Title IX investigators.

“Our investigators are trained to be impartial fact finders, including when interviewing victims of sexual misconduct,” Zlock said. “We take this responsibility seriously and strive to continually improve our skills. Our goal is to proceed as sensitively as we can when communicating with the parties involved.”

Rachel said she told the investigators about the specific order of events of her night with Joe: from telling him he had to wear a condom to when she noticed that he wasn’t wearing one. After listening to Rachel’s account, the investigators asked more detailed follow-up questions.

“They just took me back to that moment and it was like I was experiencing it again,” Rachel said. “It’s not that I thought they were inappropriate, because I understood they were just trying to get all the information possible. It was just still very unpleasant to talk about.”

The meeting lasted about 20 minutes––a lot shorter than Rachel thought it would, she said.

Rachel said she hadn’t received any updates on the investigation by mid-November, so she emailed the EAD asking if the investigation would be closed by finals, and she received a replied saying it would not. In January, while Rachel was home for winter break, she received an email from Zlock, the then-newly-named Director of Title IX and Student Discrimination, informing her that the EAD had split into three separate offices, and that Rachel’s case (like all other open Title IX cases) had been transferred over to the new Title IX Office.

In the transition to three separate offices, the EAD investigator who had originally been assigned to Rachel’s case began working for the Office of Equal Employment Opportunity (one of the other three offices stemming from the split), and Zlock would be taking the previous investigator’s place. Zlock informed Rachel that the office would need another 30 days to conduct their investigation, and asked Rachel to meet to discuss the case upon her return from winter break.

“So the first week back I met with her, and she seemed great. She seemed empathetic,” Rachel said.

During their meeting, Zlock and another Title IX investigator asked Rachel to retell her story, and asked her more questions about the incident. They also showed Rachel video footage they had pulled from dorm surveillance cameras of her entering the elevator following the incident, and of Joe talking to one of his neighbors in the hallway as Rachel left. Rachel also learned that investigators had talked to Joe’s neighbor, who said in his own meeting with the Title IX office that Joe asked him if it was bad that he didn’t tell a girl that he wasn’t wearing a condom.

“I wish I had a way of saying thank you to him, because it’s really important that he came forward and told them about this conversation they had,” Rachel said. “I don’t think I can thank him enough for that because otherwise this would’ve been a ‘he said/she said’ kind of deal.”

On Feb. 26, Rachel received a copy of the preliminary investigative report the office had compiled on the case. She and Joe each had five days to submit written comments to the report, as outlined in the student handbook, and Rachel submitted hers two days later.

“Last semester, there were a couple times on campus where I would walk by him, and I just remember freezing and this all-consuming fear coming over me.”

Following the submission of the comments, the timeline in the Student Handbook says that the office “endeavors” to review the comments and prepare a final investigative report within seven business days. Rachel received the final investigative report on the morning of April 12, which was 29 business days after the last day the students could submit their comments.

The final report found Joe responsible of sexual assault. The Title IX Office investigators make each determination in reports of sexual misconduct based on the preponderance of the evidence, or “more likely than not,” standard, Zlock said.

The determination in the final report has been forwarded to the Office of Student Accountability, which is responsible for issuing sanctions, Zlock said. When she read the findings in the final report, Rachel said she felt relieved.

“Obviously I’m happy with the way things ended up, but I don’t think that really negates my issues with how the process went,” Rachel said. “So I can be relieved that it’s over and that they’re holding him responsible, but I still say that the process was flawed; it took way too long.”

Zlock said that the Title IX office is committed to keeping all parties informed during the investigation process. However, throughout the investigation, Rachel said she felt as though she were in the dark on its status.

“I think they should’ve been the ones contacting me, because part of my fear was I’m going to piss them off by asking so much,” Rachel said. “You know, it’s probably not rational, but when you’ve been through that kind of trauma, something doesn’t need to be rational for it to feel like a high possibility.”

While the student handbook says that the Title IX Office endeavors to complete investigations in fewer than 60 days, 120 business days passed between the initial interview and the issuance of the final investigative report in Rachel’s case.

“While federal guidance does not give a definitive time frame for completing a Title IX investigation, we strive to conduct a fair and impartial investigation within 60 days,” Zlock said. “However, there are a number of factors that can impact this timeline, such as the availability and number of witnesses, documents provided and any follow up that is needed.”

Throughout the duration of the investigation, Rachel would occasionally see Joe around campus.

“Last semester, there were a couple times on campus where I would walk by him, and I just remember freezing and this all-consuming fear coming over me,” Rachel said. “There’s just not any words for it. When you see the person that assaulted you just getting to like go to class and live his life like nothing happened…”

Joe didn’t respond to the Hustler’s attempts to contact him.

While Rachel initially questioned whether she would actively participate in the investigation if she could do it over again, she looks at the investigation in a new light now that Joe has been found responsible, she said.

“I think this is a case where things actually turned out well, so now I’m like okay, maybe it was all worth it,” Rachel said. “But six months was still a long time. The fact that they found him responsible doesn’t negate the fact that it took up my entire year. I can’t get that time back. I’m still just kind of in shock, in a positive way.”

Campus climate surrounding sexual assault

Rachel is not alone. Last academic year, Vanderbilt received 246 reports of sexual misconduct and conducted 11 investigations. While the number of reports has more than doubled since the 2014-2015 academic year, the number of investigations has been cut in half––22 investigations were carried out in 2014-15. Of the 51 investigations Vanderbilt has conducted during the past three academic years, 12 have found the respondent responsible and 36 have found them not responsible. Three were still ongoing at the time last year’s data were reported. Data are not yet available for the 2017-18 academic year.

According to the Spring 2015 Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Violence, which surveyed undergraduate, graduate and professional students about sexual misconduct and power-based personal violence on campus, 13 percent of respondents experienced at least one incident of sexual misconduct at least one time since the beginning of the 2015 school year. The survey was conducted using two separate surveys, EAB and Everfi, each sent out to half of the student body, assigned at random.

Further, according to the EAB survey, 99 percent of 160 respondents who said they had experienced some incident of unwanted sexual contact said they did not use the school’s formal procedures to report the incident. Sixty-five percent of the 1300 students surveyed felt as though the accused or the accused’s friends would retaliate against someone who reports. In deciding whether or not to report, 23 percent of respondents indicated that the fear of not being believed crossed their mind.

“I think a lot of people don’t trust the [Title IX Office],” said Director of Women’s and Gender Studies Dr. Katherine Crawford. “I think they they do not trust the university generally to take them seriously because they feel that they’re not taken seriously if something goes wrong.”

Currently, the U.S. Office of Civil Rights (OCR) is investigating two Title IX complaints against Vanderbilt: one from March of 2013 and another from January 2017, according to a list compiled by the OCR. Jim Bradshaw of the U.S. Department of Education said the OCR cannot discuss the details of the current investigations. However, investigations are often opened due to a complaint regarding a school’s insufficient fulfillment of Title IX requirements and therefore “creating and perpetuating a hostile environment.” Some of these insufficiencies may include the timeliness of investigations or accommodations given or denied to the victim, such as housing changes.

According to the Everfi survey, while 73 percent of students surveyed reported knowing where to seek help regarding an incidence of sexual violence, only 34 percent said they understood Vanderbilt’s formal procedures to address complaints of sexual violence.

“We work with university partners to provide all the appropriate and available resources we have to students who request accommodations known as ‘interim measures’ through the Title IX office,” Zlock said. “Each specific request is evaluated on an individual basis; we want to assist students through this process and provide support.”

The campus climate survey also showed that 86 percent of students who responded to the survey felt as though the university would take reports of sexual assault seriously.

“I think the lack of responsiveness that everyone talks about and that statistics, though they are hard to come by, would bear out the perception that [the Title IX Office] takes forever and then the resolutions are minimal and often completely unsatisfactory,” Crawford said. “That said, my understanding is that there’s new leadership there and there’s new attention to the fact that this has been a problem, so I’m cautiously hopeful that that will change.”

According to Vice Chancellor for Administration Eric Kopstain, the EAD’s split into three separate offices should allow each office to focus and specialize more on the unique needs of the students each office serves. Kopstain also said that the university will increase staff in the offices, including the Title IX Office, as needs arise.

“I’ve had people, the people that work at Project Safe, telling me that things have improved since Molly Zlock got here,” Rachel said. “The thing is, either way, I have not experienced those improvements.”

Project Safe

Rachel lauded Project Safe for the instrumental role it plays in assisting survivors in both their own healing processes and in the reporting process.

“I worry about other girls who don’t have an Otis (McGresham) to help them through this or who have been scared away by how intimidating this process is,” Rachel said.

The Project Safe Center for Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response is a resource on Vanderbilt’s campus whose stated mission is “to provide information, support, referrals and education about sexual and intimate partner violence (including sexual harassment, sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence, and stalking), as well as consent, healthy relationships, and healthy sexuality to the Vanderbilt University community.” The center itself is located at 304 West Side Row, behind McGill Hall near Alumni Lawn.

The center offers resources ranging from advocacy services to interim measures for survivors. Students can access Project Safe resources by calling the 24-hour crisis and support hotline at (615) 322-SAFE (7233), walking in to the center or scheduling an appointment between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., and attending office hours held in locations across campus including the Commons, the Law School and the Black Cultural Center.

Project Safe became a limited confidential resource in the fall of 2016, meaning that “only statistical, but not identifying, information”––such as general non-identifying information about the nature, date, time and general location of an incident––regarding students’ reports is shared with the Title IX Office and with VUPD for tracking and compliance purposes.

There are some limitations to the confidentiality of Project Safe, including situations in which Project Safe staff feel they have received information that could be seriously or immediately threatening to the safety of campus and students, or in which the incident involves minors, among others. Additionally, Project Safe provides the Title IX Office with the name of the alleged perpetrator, if known, if the perpetrator is a Vanderbilt faculty member, staff member, teaching assistant, independent contractor, adviser or otherwise a member of the community other than a student.

“As a limited confidential resource, we offer a place for students, staff and faculty who have been impacted by intimate partner violence to seek support in whatever way they feel comfortable without automatically triggering an investigation,” McGresham, the Project Safe Prevention Educator and Victim Resource Specialist assigned to Rachel’s case, said. “That way, people can receive information and get support in making an informed choice on what steps they want to take next. We operate from a trauma-informed and survivor-centered perspective, so how a person utilizes Project Safe remains completely up to them.”

“In short, the role we play is helping people understand the options they have to move forward and helping them to navigate whichever option they choose.”

Project Safe Prevention Educator and Victim Resource Specialists can also work with students who choose to participate in the criminal justice reporting process by having VUPD and MNPD detectives come to Project Safe to take reports or by accompanying people to the police station and to court, according to the individual’s preference, McGresham said.

“In short, the role we play is helping people understand the options they have to move forward and helping them to navigate whichever option they choose,” McGresham said.

Zlock also emphasized the option of pursuing criminal allegations in addition to or in place of Vanderbilt investigations.

“It is also important to know that a Title IX investigation does not preclude a law enforcement investigation,” Zlock said. “If a complainant wishes to pursue a criminal allegation against a respondent, they can choose to do so. Likewise, a complainant may wish to pursue a criminal allegation and not request or participate in a Title IX investigation.”

McGresham began working at Project Safe in March of 2016 when his family relocated to the Nashville area. He had been working in college settings since 2003, and wanted to continue his career in student affairs. The dual function of his role at Project Safe feeds two of his passions, McGresham said.

“The Prevention Education role allows me to serve as an educator. Helping people connect their personal or academic interest to the role of violence prevention is something that I truly enjoy,” McGresham said. “The Victim Resource Specialist role allows me to serve as a support person. I meet with people who have experienced some of the worst moments of their life, and my support can hopefully make their journey to healing more bearable.”

While he noted that his job at Project Safe can be draining and frustrating, McGresham finds his work to be rewarding.

“As you look across the country, there are very few offices that do this work positioned and supported as well as Project Safe.”

“When a student connects with me because of another student’s positive experience or presentation that I did, it’s rewarding. When someone shares with me how they applied something they learned in a program that I led, it’s rewarding. When I see it click in people that violence prevention is a part of who they are, it is rewarding. Almost every day there are moments that validate our efforts and remind me that not only is the work that I get to do important, but it is making a difference,” McGresham said.

McGresham said that if he could talk to a student who had recently been assaulted, he would tell them that what happened to them is not their fault, and that their decisions on how to move forward are all their own choices. He said he would tell them that Project Safe staff will never pressure them to make a particular decision, and that they can connect with the center anonymously if that makes them more comfortable.

McGresham commended Project Safe for its exceptional work in the field of sexual assault education and prevention.

“As you look across the country, there are very few offices that do this work positioned and supported as well as Project Safe,” he said. “I was and remain excited about the opportunity that each day presents to work with the Vanderbilt community to make not just our campus but the world a safer place.”

The decision to report

While her experience reporting sexual assault has taken a toll on her, Rachel hopes that sharing her story will make others feel comfortable reporting incidents of sexual assault and inspire the Title IX Office to make changes to the way they handle the reporting process.

“My main hope is that maybe me coming forward will help someone else in the future, or that maybe Title IX will start giving people regular updates, or that maybe because mine ended with him being found responsible, other girls will be more comfortable reporting,” Rachel said.

Zlock emphasized the importance of reporting incidents of sexual assault both in eliminating interpersonal violence on campus and in providing survivors with the resources and support they need.

“Reporting is an essential part of ending sexual misconduct and intimate partner violence on campus,” Zlock said. “When a student makes a report of sexual misconduct, the choice whether to pursue an investigation, is, in most cases, theirs to make. Many people report, but opt to not pursue an investigation. However, when students report, we are able to provide support through resources and interim measures, and they are providing the university with information about the prevalence of sexual misconduct on our campus. Having a more complete picture, through reporting, about what is happening on our campus allows my department to work with campus partners in directing educational initiatives and resources.”

Rachel added that the moment Joe was found responsible served as a form of closure for her.

“It’s very validating, because as much as I say ‘Well I know what happened and I know it wasn’t okay,’ there is something positive in having other people recognize that what happened to you wasn’t okay,” she said. “I don’t even know if I would call it happiness — it’s like relief and it’s kind of shock in a positive way. I can’t believe this is finally over. So I would say in that end it’s worth it.”