One evening in February of 2015, Ryan Hawaii, an upstart UK-based artist, sought to make a statement. He had already garnered a niche presence in London’s afro-punk underground, fielding creative collaborations with the likes of Skepta while dabbling in sporadic artistic exploits of his own—but tonight, he was after something much more definitive.

He filled a hefty bag with homemade streetwear. He drew a mob of raucous teenagers to the city’s Selfridges location. And by midnight, the group stormed—if not hijacked, until security broke everything up—the installation that Virgil Abloh had set up there, illegally turning it into an impromptu brand presentation for Hawaii’s own project.

A short time after the demonstration, Abloh followed Hawaii on Instagram. No more than three months afterward, Hawaii stood side-by-side with him in the same exact Selfridges store: this time, not as a garbage bag-wielding criminal flanked by security, but as an invited guest at a sought-after fashion seminar hosted by the industry’s most prominent figure. The event centered around tips for becoming successful in artistic endeavors; Abloh had enlisted Hawaii as one of the “young Londoners inspiring him,” Complex reported. Where Hawaii planted anarchy, even at his own expense, Abloh saw an opportunity for rebirth. It’s a career-long principle that defined his tenure at culture’s cockpit: no matter what it cost him, Virgil Abloh wanted you to win.

Being in a position to call such shots insinuates winding paths to the top, marked by suit-and-tie business meetings, stern handshakes and persistent victories against the impossible. It’s not like Virgil Abloh’s ascent was exempt from similar hustle. Up to his death of cancer this past Sunday, he was relentlessly engaged. He juggled executive positions in multiple luxury menswear conglomerates; he fixed his eye on a youth culture that never stopped evolving; he was pulled from enterprise to enterprise in every waking moment, hopping from seminar to seminar, runway to runway, conversation to conversation.

The difference, though, was that when it came to Abloh, he wasn’t the coffee-clutching, suit-and-tie pessimist that the term “executive” has largely grown to connote over time. His more accurate face was perhaps best summed up by A$AP Nast, freestyling into a microphone at a Met Gala afterparty the late fashion mogul hosted this past September: “Shout out to Virgil Abloh, the biggest kid in the building,” he rasped, gauging his crowd as the instrumental jazz band BadBadNotGood jammed beside him. “Virgil’s the biggest kid here. He’s just dreaming.”

Virgil Abloh operated with a childlike inventiveness that drew as much criticism as it did glory. Whereas olden upper-class champions of youth culture, like Vogue’s Anna Wintour, often don inconspicuous, closed-off personas—interning at the Met as a high-schooler, it was a strict rule that if any of us ever crossed paths with her, we weren’t allowed to start conversations or else she’d get annoyed—Abloh saw youth not only as a target audience, but as a target muse. The dominant archetype of luxury exec, characterized by figures like Matthew M. Williams and Marine Serre, often postures itself to be a deified genius under which aspiring emulators ought to take notes; social media accounts are robotic megaphones for brand announcements, interacting with either very close collaborators or no one at all. A stark iconoclast, Virgil Abloh was following 8,979 people on Instagram and Twitter combined at the time of his death. He was inspired by the unsuspecting, invigorated by the gutsy, interested in the everyday—and you didn’t have to hustle across town and slip a business card under his office door at 5 a.m. to get on his radar. All you had to do was do.

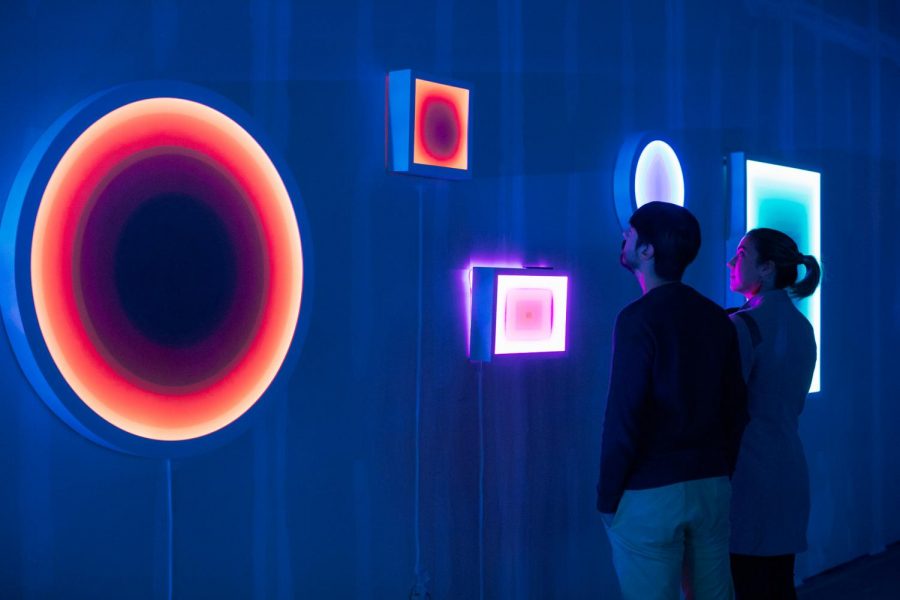

For as much as he was the face of an artistic movement, Abloh never purported to have the answers, nor be exempt from the darker underbellies of his many playing fields. In his 2019 Chicago exhibition “Figures of Speech,” for instance, there was one section in which an audience member could stand at the center of the floor, looking upward at large posters of young black children playing with Louis Vuitton products, and then shift their gaze downward to an assortment of 16 numbered crime scene markers—a nod to the amount of shots fired at Laquan McDonald five years prior by a Chicago police officer. Both masterfully and eerily, Abloh juxtaposed highbrow consumer culture with the grim realities it inherently undermined. In the tagline for his long-revered self-created streetwear brand, he declared himself to be “Defining the grey area between black and white as the color Off-White.” The statement has been worn on black feet and white feet, sold by the truckload for thousands of dollars apiece and given away for charity, emblazoned beneath the silhouette of Michael Jordan and plastered onto knockoffs bought on the cheap. In an era that sees human coexistence constantly complicated, it’s moving to see its crevices so broadly magnified: whether it was in the schoolyard, the top floor of the suite or the Louis Vuitton runway, not only was Abloh’s fingerprint a common denominator—it was hyper-visible, meant to be contemplated in collectivity rather than omnipresent in silence. He started a dialogue. And the dialogue outlived him.

But this doesn’t mean the dialogue has always been good. One oft-cited example came in the summer of 2020, when Abloh was enlisted to do the album artwork for Pop Smoke’s first posthumous LP, “Shoot For The Stars Aim For The Moon.” In a written statement, Abloh explained that the cover had been inspired by a conversation he had with the late rapper, wherein he realized that “his story felt like the metaphor of a rose and thorns growing from [the] concrete of his hood in Canarsie, Brooklyn.” In the original version, a photo of Pop Smoke in an Off-White top—gifted to him by Abloh for that year’s Paris Fashion Week—sat, stern-faced and emergent, amidst an assortment of barbed wire and metallic roses.

“Hey Virgil we need new album art, they ain’t going for this bullshit,” 50 Cent said, echoing the concerns of many dismayed fans. In a since-deleted Instagram post, Pop Smoke’s manager declared, in demanding a redo: “POP WOULD LISTEN TO HIS FANS.”

Although the album artwork was eventually changed to a single metallic rose against a black background, the original—along with the backlash it received—paints an all-encompassing picture of who its mastermind was at heart: Virgil Abloh was obsessed with extracting beauty from the mundane, mythography from normalcy, roses from concrete. And the same way that the album cover was greeted with revulsion, so were many of his attempts to apply subversive narratives to the fashion industry he commandeered.

Reviewing “Figures of Speech” for Frieze, the critic Evan Moffitt shared a grievance with many who frowned at the means to Abloh’s prominence.

“When Abloh was appointed the artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton in March 2018, the news sent a shockwave through the fashion world,” Moffitt said. “Abloh, though, is an arch-appropriator, and his vetting seems to have been done at hyper-speed. Little more than five years earlier, he was largely unknown, the founder of a small label called Pyrex Vision, which sold USD $40 Champion brand t-shirts printed with the word ‘PYREX’ (the glassware used to bake drugs), the number 23 (from basketball legend Michael Jordan’s jersey) and a reproduction of Caravaggio’s “The Entombment of Christ” (1603–04) for $550 apiece.”

When I was in high school and quotation marks and zip-ties began gradually making their ways onto the sneakers of my classmates, I was a staunch detractor of Abloh’s work for similar reasons. It was commodification at a comic extreme, a Warhol-esque gag about consumerism for which we, the punchline, were blindly emptying our wallets, laughing through it all.

But read into the exact same prospect—Pyrex glassware, the number 23, “The Entombment of Christ,” all on a shirt for $550—and the implication becomes clear: Not only are a drug-making material, a basketball superstar and a Renaissance-era painting in the same conversation, but they’re all worth the same thing. It’s both utopian and dystopian: eclectic cultures are occupying the same playing field. But, for a slice of the dream, you must empty your pockets.

Call it what you want. Whether we were fans of it or not, in a society where similar hypocrisies long made visions like his impossible, Virgil Abloh played the game—and he won.