Vanderbilt professor of computer science and computer engineering Abhishek Dubey received a combined $3.9 million dollars in grants in September from both the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy to fund a revolutionary real-time transit system for the Chattanooga area.

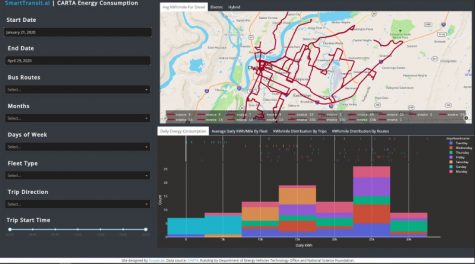

Dubey’s project, dubbed “Smart Transit,” relies on continual data collection and machine learning to address public transit problem areas, such as energy efficiency and real-time response mechanisms.

At the moment, Dubey and his team are gathering data and developing algorithms, but plan to implement the software several years down the line. One area that particularly differentiates Smart Transit from the current public transport system is its Uber-like response initiative. This means many previously fixed routes will be flexible to change according to the immediate needs of commuters.

“Sometimes efficiency means you will actually take out one of these fixed lines and introduce on-demand service,” Dubey said.

With Smart Transit, commuters would be able to immediately signal their need for transportation through online methods. However, unlike commercial alternatives such as Uber and Lyft, this system is not motivated by economic objectives but will instead emphasize transport equity. One such on-demand focus of Smart Transit will be the optimization of “paratransit services,” which serve commuters with disabilities who are unable to access regular transit services. Through more rapid and efficient individualized transportation, Smart Transit aims to maximize the percentage of daily trips provided by paratransit services.

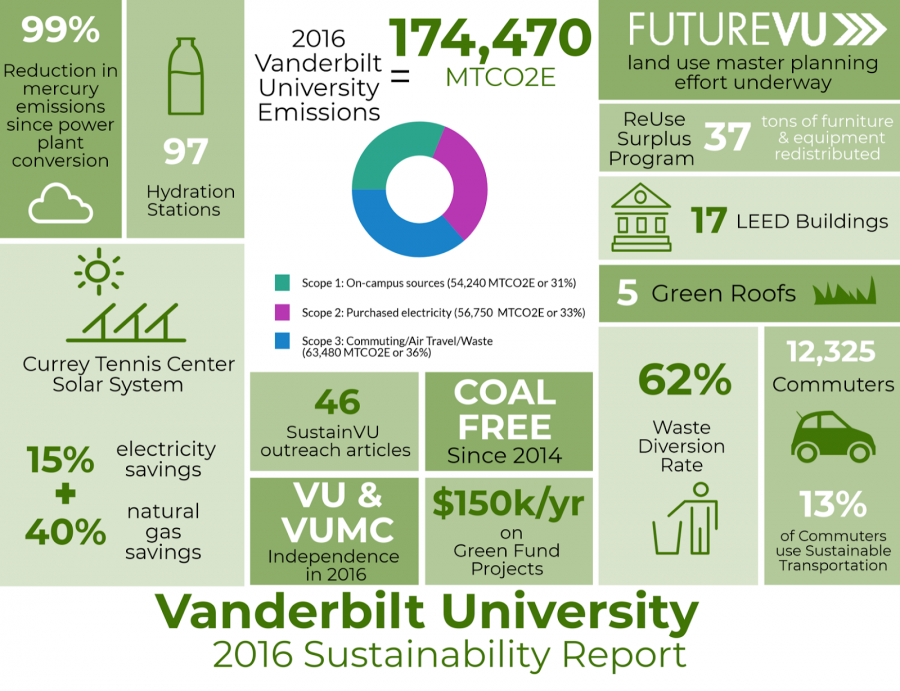

Another priority of Smart Transit is to increase the energy efficiency of bus routes in order to save public transit companies money. Dubey’s program continually collects data for the different vehicles within the Chattanooga public transit system umbrella to determine their fuel usage rates. This collection includes variables like engine idling status, engine temperature and vehicle speed.

Based on this data, Smart Transit is working to develop algorithms that would allow public transit companies to systematically deploy their limited vehicles on cost-effective routes, rather than on their current, less intentional dispatches. However, this is easier said than done.

“The complexity of the problem is so huge that you cannot use classical methods,” Dubey said. “Hence, you start using machine learning methods.”

The frequent and variable decisions needed to run a demand-based transit system necessitate a less traditional algorithmic approach. Machine learning allows algorithms to learn from patterns and develop a flexible system, that in this case, would be able to address the ever-changing factors present in public transit, Dubey said.

Though unique in its approach, Dubey’s Smart Transit isn’t the first initiative to tackle the idea of a real-time transit service. Dubey’s team believes that the failure of past initiatives is in part due to a lack of bringing multiple disciplines together and addressing the community’s concerns.

“Before you go and actually design a service for an area, you really need to try and understand, will the people use the service you’re coming up with,” Dubey said. “You need to take a look at the social science, and you cannot just come in with the technology hammer and try to hammer your way through.”

With the expertise of fellow Vanderbilt professor, Paul Speer, chair of the Department of Human and Organizational Development at Peabody College, Smart Transit plans to incorporate a socio-relational approach, which directly involves the community’s opinions.

“When introducing a new technology to a domain people are accustomed to, it’s necessary to gauge citizens’ intent to actually use the technology,” Dubey said.

Through focus groups and organization-based survey methods, among other techniques, Smart Transit intends to reach the community directly and figure out their needs, their roadblocks and, consequently, how to address them. In an age increasingly dominated by dystopian projections of the future in film and television, buzz-words like “artificial intelligence” or “machine learning” often set off mental alarms. However, in this case, the seemingly ominous “machine learning,” used in this project is nothing to worry about.

“As far as the university’s research is concerned, these processes have to be made public,” Dubey said. “We keep telling people precisely the kind of data we collect and the kind of processes we go through. Right now, the good thing is none of this data is personal, identifiable information.”

Smart Transit only measures data that’s completely removed from personal identification (such as passenger onload and offload and fuel consumption), so the ethics of Smart Transit’s machine learning isn’t a concern. Dubey’s team has taken all the necessary precautions in order to preserve passengers’ privacy, by solely collecting numerical data for their algorithms.

Though this project will need multiple years of survey and data collection, as well as unique algorithms, before it is ready to be launched onto the streets of Chattanooga, Smart Transit is already well on its way to revolutionizing the way we use public transit.