As a freshman in the College of Arts and Science, I have often wondered about the significance of AXLE (Achieving Excellence in Liberal Education). When I say this, I am not being a bitter humanities major forced to take calculus, or a STEM major forced to read Shakespeare, (again?!) I am coming from a position trying to understand and maximize the benefits of AXLE.

A structured curriculum is a common practice across the best U.S. colleges, such as University of Pennsylvania, Williams College, and Stanford University. The goal of such a curriculum is to develop intellectual perspectives and skills through the liberal arts and sciences; namely, as Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Science website puts it, “[to] receive a comprehensive, academically rigorous education that primes [students] for success in every area: scholastic, personal and professional.” However, students have often found themselves at fault with the system, complaining and collectively scraping for an easy way out of these requirements. Students consider AXLE a burden rather than an intellectually stimulating and beneficial construction––its intended effect is lost in action. Therefore, it’s crucial to ask ourselves: what are we supposed to get out of AXLE, and if we are not, what can we change about it?

When we graduate, having completed AXLE, it is not that list of diverse-looking courses we’ve completed that primes us for “success in every area.” Instead, it’s perspectives and skills we’ve gained and used across classes in different fields and professions that adds value to our rigorous education.

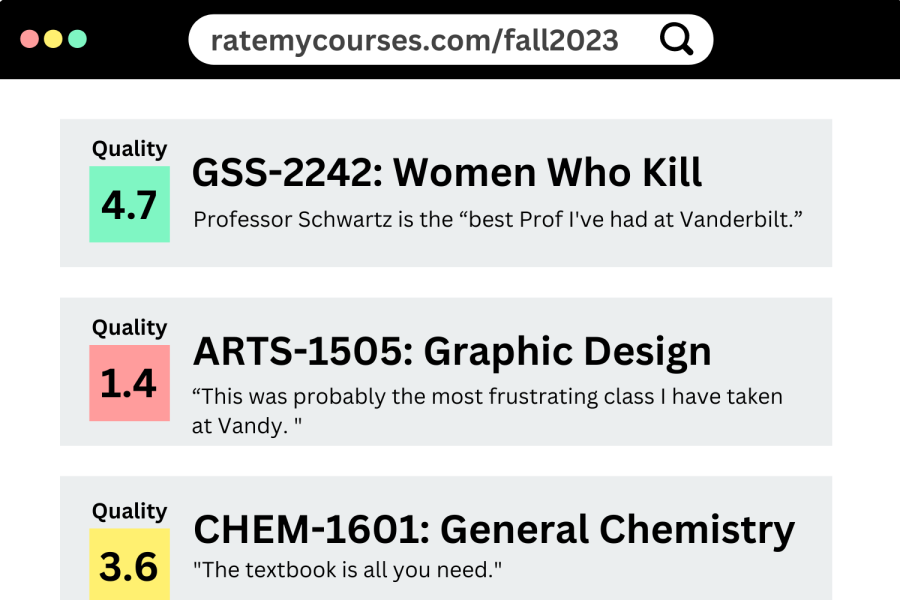

Simply providing a list of courses that satisfy a few boxes of requirements is not a liberal arts education. However, that seems to be what AXLE is. Because of AXLE, departments and classes should make more of an effort to teach students how and why particular classes and materials could be used in a broader context.

For this reason, there ought to be more interdisciplinarily designed courses that draw on materials from different fields and departments to complement and fulfill a program like AXLE . For example, an introductory art history class could help students understand how values of aesthetics inform decision-making, a helpful perspective that benefits not only art history majors. This would allow students to feel encouraged rather than burdened to explore classes outside their majors knowing that these classes will be beneficial beyond fulfilling a requirement. Introductory level courses in each department, at least, should benefit majors and non-majors alike. More importantly, it is through realizing and discovering the intersection across different fields that students are able to translate interdisciplinary ideas in not only scholastic but also personal and professional growth. Rather than forcing students to simply learn material from different fields, AXLE needs to teach students how to think across disciplines. However, without institutional efforts and changes currently in place, it is hard for students to connect the dots.

It is true that the current system has its merits. In the course of fulfilling AXLE, students often confront courses from, and may lead students to ultimately major and minor in, diverse combinations of fields. Such course diversity can hone their educational background to stand out in the eyes of employers and graduate schools. However, without the necessary changes and guidances, not every student will find AXLE beneficial in such a way.

In order to do so, students need more cohesion and direction in choosing classes that fulfill the different sections of the Liberal Arts Requirement, instead of scraping for easy classes to fulfill them. Students would be better off taking a specific sequence of courses that would provide them a cohesive set of knowledge and skills. For example, if I am a political science major, I would benefit from a sequence of courses in math and statistics that provides me with a theoretical and practical mastery of statistical analyses. This would allow me to observe and analyze socio-political changes in a brand new perspective. Although AXLE seemingly provides liberty and flexibility by allowing students to choose freely from a breadth of classes for each requirement, a lack of direction and cohesion is frustrating and thwarting.

It is apparent across campus that students struggle with AXLE. Students often call their AXLE classes “random” and “irrelevant” when AXLE has the intention and potential of becoming a more signature part of our undergraduate curriculum. It could provide students the essence of a liberal arts education: a versatile and transferable set of skills and perspectives that prepare students for intellectual and professional endeavors. However, without more institutional attention, effort and changes, AXLE will be nothing but a name; nothing but a bureaucratic process; and nothing but a nuisance for students trying to piece together an education from which they want to benefit from and be proud and confident about.