Author’s Note: Mu Mu is the nickname that storytellers like my mother, grandmother and her mother, have passed down to me. Word around our village is that storytelling is our archive, preserver and the author of our existence. Vanderbilt, through this letter, I hope to share with you that while others’ worlds may not affect you, they still exist. Ask questions. Learn. How do we actually foster and practice inclusivity at Vanderbilt? Allow me to take your hand and tell you the stories of those who have come before me and of those who will continue to come after me — despite erasure.

Dear Vanderbilt family,

I’ve rearranged and discarded this letter each of the other nine times that I’ve tried writing it.

In 1948, Burma gained its independence from the British. Quickly after, Burmese government forces began the killing and erasure of indigenous ethnic groups such as the Knyaw Poe (Karen people) — my people. In 1949, Knyaw Poe Saw Ba U Gyi established an insurgency group against our oppression. While the Burmese gained their independence, we officially lost our everything. Our homes. Our family. Our food. Our dignity. Erasure.

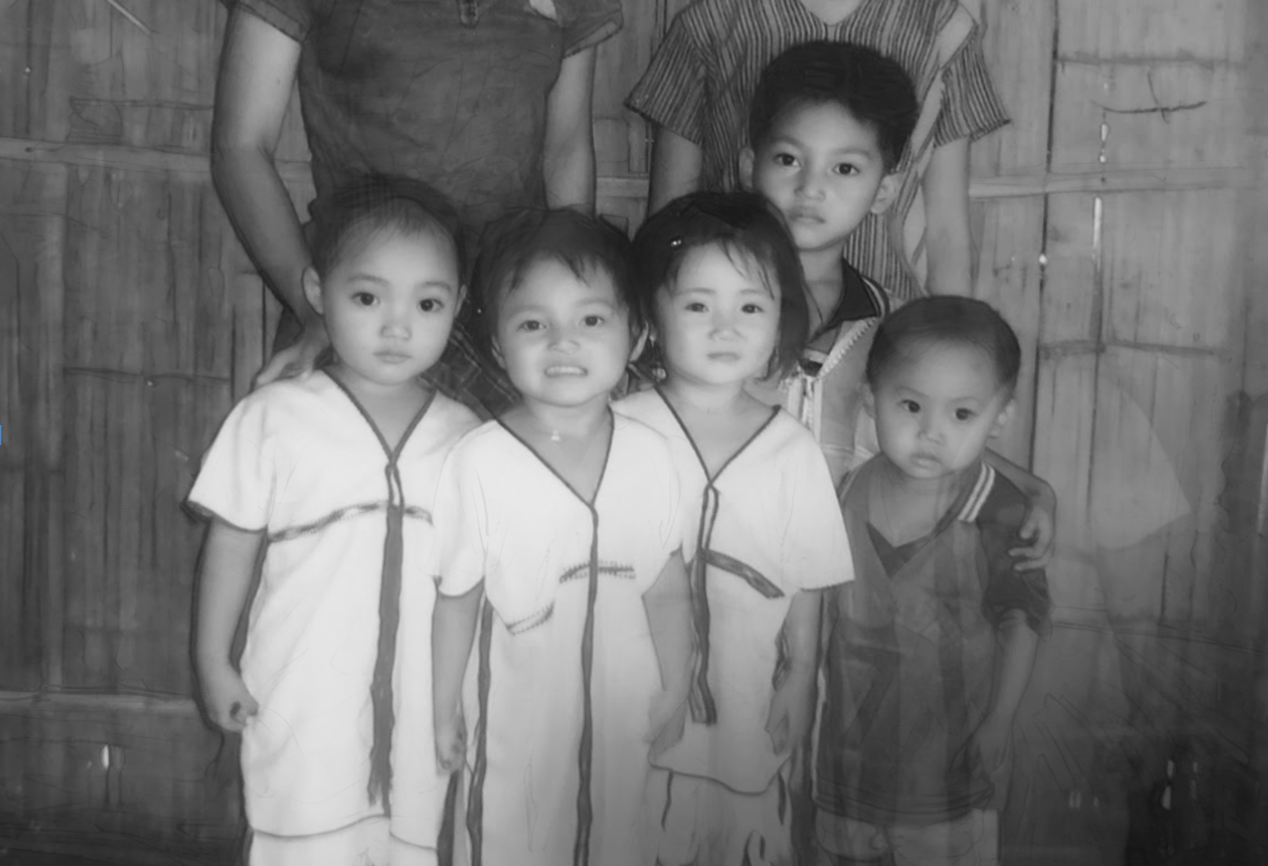

I was born in the heart of Burma’s jungle near the Irrawaddy Delta Basin, ထံထၣ်စွ့ . My nursery, with its straw-like thatch, bamboo shoots and blue tarp, is the closest I’ve come to feeling a sense of community and belonging. However, raised in a refugee camp along the border of Burma and Thailand, I was without a birth certificate, and thus, my status was declared as “stateless.” In our state of refuge, we were denied our ethnic diversity. Here in America, we are denied our ethnic legitimacy. Erasure.

When you see me, what do you see? Do you see just another Asian girl attending an institution that she and her parents have always dreamed of? Do you see or subconsciously think of just another typical model minority? Who do you write me as? Erasure.

Here is how I hope to be seen and heard. From the way I talk to the way I walk, see me as Knyaw Poe. See a girl who is carried by the resilience of her people. I don’t beg of you to know me. I just beg that you don’t erase the existence of my people, their struggles and their resistance. My parents’ only dream for me was to survive. Please, don’t erase the fact that my people are still fleeing their homes and holding onto the last bits of their land. But please also don’t reduce the identities of our people to their suffering. Don’t do that to anyone.

You may ask, “Why does this matter?” It may not matter to you, but it could to those around you. Many on Vanderbilt’s campus are trying to feel okay and pursue their dreams, all while watching their loved ones be torn apart literally and figuratively. If you truly care about fostering safe, inclusive and welcoming spaces, let’s not see each other as monolithic beings. This “mono” erases people and history.

Vanderbilt, make room to listen to one another. The university’s fall 2024 demographics report indicates a racial/ethnic breakdown of 41.3% white, 18.5% Asian American or Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 12.3% international, 9.4% Hispanic or Latino, 6.6% unreported, 6.1% Black/African American, 5.6% Multiracial and 0.1% American Indian/Alaska Native. Have we ever stopped and slowed down to consider that some may not feel like they belong to any of these categories but had to click one?

Vanderbilt, I come to you not with unreasonable optimism and naivety but with hope. I come with the alive and persisting spirit of Kawthoolei, our home.

From meeting other students who also have to live thinking about their nationhood and citizenship every day, I’ve seen that being denied the space to unpack with others is painful. To not feel belonging is one thing. But to hear others say, “I see my family being murdered every day and feel like I can’t even be seen by the BIPOC community here,” is another. It hurts.

To friends from an unrecognized nation who crave the feeling of representation on this campus, I can’t provide you with a feeling of “home.” But I hope that after reading this letter, you feel less alone and better understood. And while we may make up a small percentage of the campus population, we too deserve to find each other and feel safe.

If you’ve ever had to feel indifferent in order to not feel different from this world, I invite you to feel the feelings. Be sad. Be mad. Be joyful. Be loving. Be all of the above. Just be.

Today is Knyaw National Day, Feb. 11, 2025. This day commemorates the resilience and strength of Knyaw Poe. For over 75 years and counting, our people have experienced theft in every form. Theft of land. Theft of the body. Theft of the mind. For 75 years and counting, the longest ongoing global civil war continues — indisputable genocide persists.

To others that have been painstakingly punctured by words like, “In twenty years, you will only be able to find Karen [knyaw] people in museums,” persist.

To the storytellers in your life and mine, choose to alter and rewrite those words.

“In twenty years, you will only be able to find [artistic, innovative, and intelligent] Karen [knyaw] people in museums,” Army General Shwe Maung said in 1997.

Ask questions. Learn.

I am not just an Asian. ယမ့ၢ်ကညီ (I am Knyaw).

Love,

ခုၣ်ဆၢဆၢဂ့ၤ