I didn’t vote in the 2024 election.

Not because of a criminal record, recent citizenship changes or a lack of trying, but because of flaws in the way my county counts votes and a lack of accountability for state and local governments on following through with the promises they make to voters — particularly, out-of-state students.

The first problem I encountered was a discrepancy between my voting records at the county and national level in August 2024. According to usa.gov, I’d been a registered voter since 2022, but my county and state voting websites reported that I didn’t even exist. Given everything else that occupied me at the beginning of freshman year, I figured this issue was something that would be fixed as others, too, would encounter this problem. In early October, when I checked again, the websites finally reflected my accurate voting status. At this point, I assumed my issues were over.

In advance of the deadline stated by the Florida Division of Elections, I submitted my request for a mail-in ballot on Oct. 23, 2024. Minutes later, I received an email confirmation that I would receive a mail-in ballot to my home address while they processed my request for a mail-in ballot delivered to Vanderbilt. As could be expected, these changes were not reflected on the voter registration websites.

My hometown guarantees voters requests to be processed and accepted within a given timeline by both state and county policy. However, by Oct. 28, I noticed that — despite receiving confirmation that a ballot would be sent in the mail to my home address — there was no record of these changes anywhere outside of my email. Over the course of three days, I spent nearly seven hours on the phone with three different election offices. I was told that they didn’t know what they could do, couldn’t see my request and didn’t have the power to help me at that time; that my request had been processed, that my request hadn’t been processed and that I should call an upper-level office. When I did so, I was told I needed to request an address change and a mail-in ballot on separate forms in a specific order, the deadline is a processing and not a submission deadline, and, lastly, that it was too late to help me and to try my luck with the midterms. After all those calls, the only information that didn’t change from office to office was that I should try calling someone else.

While it’s possible that filling out my request for a ballot earlier would have granted me better odds at receiving it, whether I received a ballot or not should not be left up to chance. I should be guaranteed that the governments will abide by the deadlines they set when processing requests.

Luckily, three alternatives exist for students who don’t receive their mail-in ballot.

First, if an absentee ballot doesn’t arrive, states may allow another person to pick up and fill out the ballot on your behalf. This rule means completing a form and, for Florida, submitting it through the same email that failed to process my address change request originally. Further, this route requires a student’s initial request to receive an absentee ballot to be processed. This step never occurred with my ballot, making this option unviable.

Second, a student could fly to their home state to vote in person. This caveat limits the ability to vote to students with the financial means to make last-minute trips home. Additionally, in many states, a student would be required to make an additional request through their state or county elections office to be allowed to vote in person as opposed to their original plan to vote by mail.

Third, in certain states, it is possible to vote in the state where you attend university. This rule holds true for Tennessee, where — as long as you have proof of attending school in the state — you can vote as a resident. The issue is, once again, the timelines. To vote, you must register 30 days in advance of the election, many weeks before you would realize that your request for an absentee ballot hasn’t gone through. Further, I would rather vote in my home state, as state policy was up for vote during the election. I imagine other students might feel the same way.

However, with all of these options, the nonarrival of a ballot is the only notification many voters receive of problems with their registration; by the time this issue arises, it is often too late to make changes to your voting plans. Further, there’s no guarantee that any of these new requests will be processed on time. While, as citizens, we have the responsibility to vote and should be willing to make some sacrifices in order to have a voice in the elections, in reality, as a result of the timeline for having your ballot request approved and the costs — both monetary and timely — of solutions, they are not feasible. In a democracy, we should be able to have the faith that we will not only be capable of voting, but that our government will actively work to follow through with the voting procedures they themselves have outlined.

Requesting a ballot isn’t the only thing restricting students from voting, either. In states other than Tennessee, there are restrictions on the types of photo identification that can be used when voting on election day. From requiring driver’s licenses issued by the state in which you’re casting your vote to utility bills from the last 90 days for proof of residence, these policies disproportionately affect the votes of out-of-state students.

When asked about her plans for voting, first-year Ella Abarquez said she was frustrated at not receiving her ballot despite meeting the deadlines.

“I did not receive my ballot. That is the frustrating part. I applied in late September. My application got approved in mid-October, and still, as of today, it says my ballot was mailed to me Oct. 22, but I haven’t received anything,” Abarquez said.

When asked if she pursued the issue, Abarquez explained that she instead patiently waited for a notification from Texas about her ballot.

“As it got closer to the election, I just figured it would be horrible calling the election officials,” Abarquez said.

While these policies aren’t voter suppression in the traditional sense, they do obstruct student voting. For students busy with midterms, work and the beginnings of adulthood, there isn’t time allotted for navigating the complex and often contradictory county-specific voting laws or federal, state and county-level elections offices.

The solution to these issues can be built on structures that already exist within the infrastructure for voting today. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, election offices are required to notify a voter if their mail-in vote is not accepted and explain how to have it counted. Would it be so hard to extend this process to include notifying people when their request for an absentee ballot is denied? If, as the election approached, voters receive messages from campaigns saying that they can see that someone at a certain address hasn’t voted, why can’t counties or states do the same and reach out when they can tell people at certain addresses haven’t registered/mailed back a ballot on time?

Another solution would be allowing voters to request provisional ballots if the state or county has made a processing error out of the voters’ control. This option would not be without precedent, as Georgia already allows voters who lack the necessary photo identification to receive provisional ballots. Additionally, provisional ballots are already provided if large groups of people find their ballots delayed through the mail. Just as citizens have a responsibility to vote, states have the responsibility to make voting accessible. We need streamlined channels to request ballots when they are delayed by the postal service or processing errors.

County and state divisions of elections need to be accountable to their constituents — those to whom they promise to give a voice. Their policies should not only exist to provide guidelines for the actions of citizens but also as guidelines for what their own mandated responsibilities are. It shouldn’t be necessary to have a plan B for voting; it should be guaranteed that if the instructions are followed as they are outlined, your plan A will work. When the bureaucracy fails, there needs to be a system in place to protect us from having our ability to vote obstructed. These issues with voting at the county level are not necessarily malicious, but they are issues that require solutions immediately.

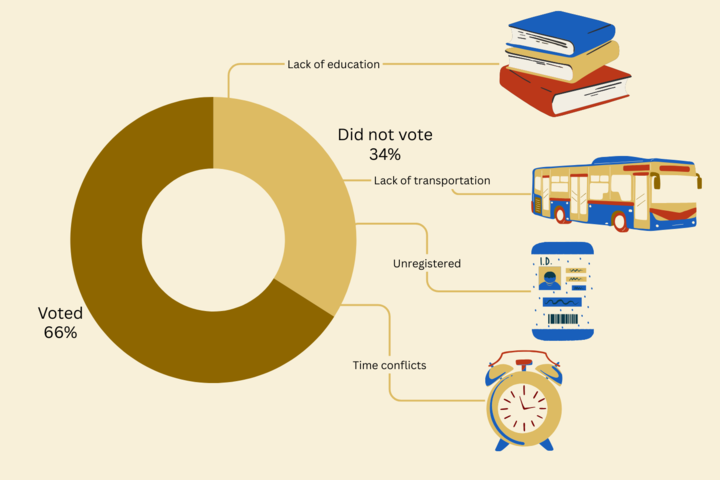

I understand that voting can’t always be easy for students living far from home. Some security measures can lead to safer, more secure elections. However, when eligible voters are not voting, these security measures become antithetical to their purpose. The vote will no longer capture the views of the entire county, state or country.

When elections are focused so heavily on voter turnout, it is more necessary than ever to ensure that voting becomes accessible for everyone, especially disproportionately affected demographics, like students voting out-of-state.

Cat • Jan 30, 2025 at 8:40 pm CST

I noticed this was written by a staffer in training. It is such a well-written, lucid article. The lead sentence caught my interest, and the article kept my interest through the end.