Editor’s note: This piece contains mention of rape.

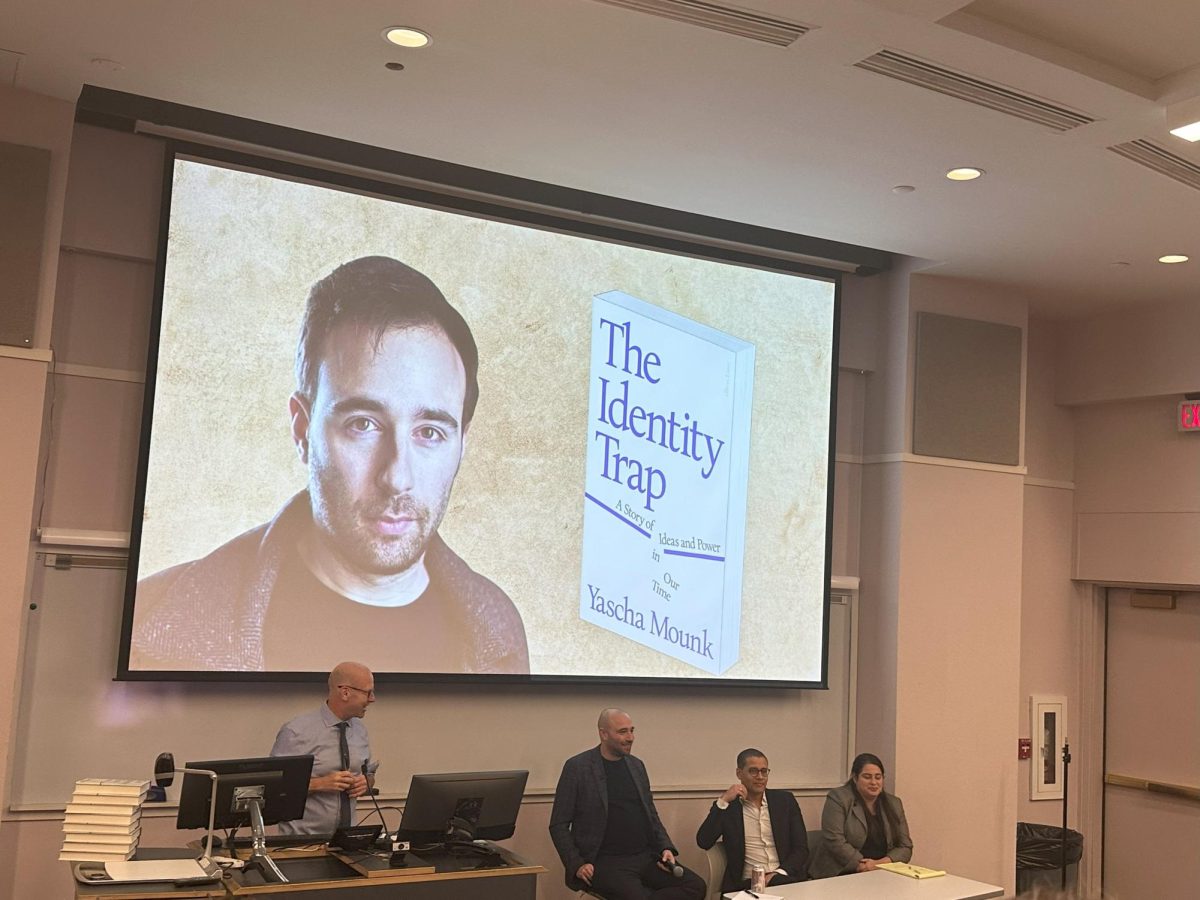

Dialogue Vanderbilt hosted Yascha Mounk — a political scientist, author and associate professor of the practice of international affairs at Johns Hopkins University — on Nov. 12. The discussion was held during Vanderbilt professor of sociology and medicine Jonathan Metzl’s “Guns in America” course and focused on overcoming identity politics when making sense of the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

According to The Dartmouth, Mounk, who is also a visiting professor at Dartmouth University, was accused of rape by Celeste Marcus, a journalist and managing editor of The Liberties journal, in June 2021. The Hustler asked Sarah Igo, one of the directors of the Open Dialogue Vanderbilt Fellows program, whether they were aware of the allegation when inviting Mounk.

Igo said the allegation was taken seriously, explaining the process by which speakers are chosen.

“We have to plan approximately a year ahead to secure highly sought-after speakers, meaning that all three [Open Dialogue Visiting Fellows] invitations were in the works before we learned of the allegation against Mounk,” Igo said.

Igo also said that Mounk remained an Open Dialogue speaker after consideration on the part of university officers and external investigations.

“We carefully considered how to respond and consulted with multiple university offices and senior leaders to make sure we were proceeding in the best interests of the campus and our students,” Igo said. “Ultimately, what was important for us in honoring the speaker agreement was that the allegations have not been substantiated and that Professor Mounk remains a faculty member at Johns Hopkins University, which conducted its own investigation.”

Analysis of election results

Mounk began the discussion with a breakdown of the election results, explaining the political significance of the 2024 race and the questions that arose following President-elect Donald Trump’s win.

“I think last week’s election has been the beginning of the Trump era in American politics because this time around, he managed [a] very unusual comeback,” Mounk said. “He won two non-consecutive terms, something that only one other American president managed to do, and that was over 100 years ago. The question becomes, how is it that Donald Trump has been able to do that?”

Mounk explained how changing demographic trends across the U.S. played a role in the election results, citing voter dissatisfaction with the incumbent party and a late campaign start as possible reasons for Vice President Kamala Harris’ defeat.

“There’s always many factors that explain what’s going on in an election, and this is no exception,” Mounk said. “Joe Biden was an unpopular president. There has been inflation for the last two years [that is] more strong in the United States than in a good number of other countries.”

Mounk elaborated by discussing what he felt were the more significant setbacks behind the Democratic campaign, explaining how he believes these point to rudimentary issues within American political institutions.

“It’s not that Donald Trump is very popular when you look at opinion polls,” Mounk said. “It’s that Democrats are very unpopular as well. This is rooted in a fundamental crisis of trust in American institutions — a crisis of trust which affects all kinds of different institutions that I personally care about — and [that] many of you, I think, care about.”

Understanding both sides

Mounk then transitioned to an explanation of why Americans voted the way they did, and how voters on both sides of the political spectrum can strive to understand the logic behind voter choices.

“[A lot of Democratic voters] today are highly educated people living in some of the more affluent parts of the United States,” Mounk said. “They are products of a meritocracy, with people who have reason to be optimistic about the future. The problem is that this group of people has become quite deeply alienated from the views, the values and the struggles of ordinary [people].”

Mounk said voters should not rush to make moral judgements towards an opposing political party without, at minimum, understanding the nuances behind a vote.

“When an election doesn’t go your way, it’s easy to think, ‘Oh, it must be that a lot of people have horrible values, that they’re bad people, that they’re racist, sexist or homophobic,’” Mounk said. “But, in my experience looking at opinion polls, most people aren’t super interested in politics. They didn’t necessarily go to college. But they reflect about the world in, I think, [an important] way, trying to make sense [of] it.”

Mounk pointed out that regardless of party affiliation, Americans’ viewpoints towards human rights issues have become more progressive across the board. In Mounk’s view, that fact debunks the notion that certain political affiliations do not care about social issues.

“Most Americans think that ethnic diversity is a good thing in America, [and] only 15% of Americans disagree with that,” Mounk said. “[But], they also want to have clear control of the border. The clear majority of Americans support gay rights, and there’s a clear majority of Americans that believe in a lot of trans rights. However, they also have some concerns about the position that [politics] are taking on [trans people], [like] trans women competing in women’s sports.”

Mounk followed up by saying regardless of their political leanings, Americans should not lose sight of the social progress made in the previous decades.

“It is offensive to people who lived in the past to say that we’ve made no progress on race considering what [racial relations in America] used to be,” Mounk said. “It is offensive to people in the past to say we’ve made no progress on how we treat members of sexual minorities when they could [have been] jailed for engaging in gay sex in the past, and today we have gay marriage on the books.”

Identity politics

Mounk transitioned to a discussion of identity politics and the role he believes it played in the presidential election. He acknowledged that the concept has always existed, but in his view, identity politics have become too divisive in recent years.

“When I look at some of the figures that I most admire in American history, I think it’s a fair description that they might engage in identity politics in one kind of sense,” Mounk said. “But that form of identity politics wars took a particular form, which is to demand for inclusion under a set of existing universalist communities.”

Mounk explained that finding common ground between groups is an integral part of having productive conversations about politics. He also said that identity politics can — in some contexts — become a form of activism that goes “in the wrong direction.”

“What I worry about here is a set of social and pedagogical practices that have really embraced [entrenchment in identity politics],” Mounk said. “For example, let’s say teachers come into classrooms when kids are seven or eight years old and split them up by identity group or race. The idea [is to] give them a kind of consciousness of a group and get them to fight against injustices. The result of this is unsurprisingly counterproductive.”

Mounk expanded on this example and connected it to modern issues with identity politics as they exist within the electorate.

“The result of this [classroom experiment] is not that kids are going to be aware of white privilege,” Mounk said. “They are going to take away that the most important thing about [them] is that [they] are white. That’s what [their] teachers are communicating to [them], and so they’re going to do what every group in the history of the world has done, which is fight for the interests of [their] group. This is the approach that people have [in politics] today, and it is not productive.”

Faculty and student reactions

Jennifer Safstrom, Vanderbilt Law School professor and director of the Stanton Foundation First Amendment Clinic, was a panelist in the discussion. She expressed her gratitude for the discussion, believing it was important in terms of processing the election results.

“The opportunity to participate on today’s panel was really important to continue campus efforts to further discussion on a range of issues across campus,” Safstrom said. “[These efforts] bring in experts from all different practice areas and backgrounds [who] share their expertise in contributing to the campus’ ongoing dialog of these issues, particularly in light of the election [and] in ways that affect our day to day lives.”

Sophomore Alyssa Newson said that while the discussion was enjoyable, she was wary of Mounk’s allegations and felt that Open Dialogue speakers should be vetted carefully.

“I think the lecture itself was informative and interesting. I especially enjoyed hearing from the panel,” Newson said. “However, it does make me uncomfortable now knowing that a person accused of sexual assault was invited to Vanderbilt’s campus. Generally, I think speakers should be screened carefully before being invited to campus.”