This year, I was one of many who bawled their eyes out to Netflix’s “One Day,” which is another book-to-screen adaptation of David Nicholls’ sensational slow-burn romance between the cheeky Dexter Mayhew and introspective Emma Morley. Back in 2011, “One Day” was adapted into a film starring Anne Hathaway as Emma. In the new TV show, which was released in February of this year, Emma Morley was played by the talented Ambika Mod, an up-and-coming South Asian actress in the U.K. Given the casting for the 2011 adaptation, many were surprised that Netflix casted Mod as Emma (myself included). It is not often that we see a South Asian woman playing a lead role in Western media, especially not opposite a conventionally-attractive white man like Leo Woodall.

The first few episodes of “One Day” make it abundantly clear that the show is a thoughtful and tasteful infusion of South Asian representation on screen. Mod, who deeply embodies Emma’s lust for life and ever-so-complicated feelings for Dexter, is the furthest you can get from a diversity hire. Her skillful interpretation of the role is evidence enough that she was chosen for her acting chops and not just the color of her skin. Despite this, I still struggled to embrace her as Emma. After some serious self-reflection, I arrived at a somber conclusion. My reluctance to accept Mod as Emma had nothing to do with her acting or her on-screen chemistry with Woodall and everything to do with my inability to fully compute a brown romantic lead in Western television.

It turns out that I’m not the only South Asian who felt this way. Mod herself couldn’t imagine playing a romantic lead; she actually turned down the initial audition for Emma. Why, you ask? As Mod explained in an interview with Cosmopolitan, it’s the lack of representation the South Asian community has had in film and television leading up to this point that made her feel unfit to play Emma. I didn’t grow up seeing melanin-rich folks like myself breaking hearts on screen and neither did Mod. Growing up without that narrative has made it difficult to imagine ourselves in a world — fictional or real — that makes us the desirable protagonist.

Growing up South Asian in America

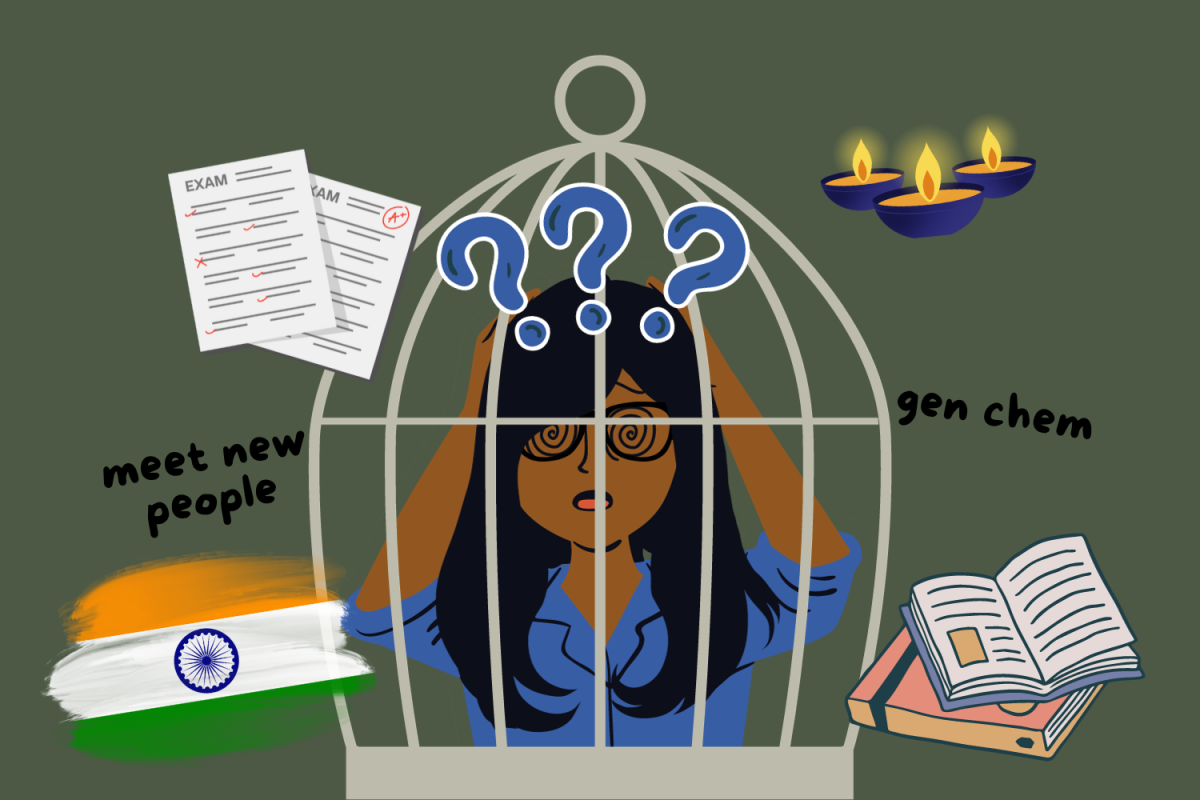

Many of my insecurities today are vestiges of the insecurities I developed as early as ten years old. In the middle of the 5th grade, my family moved to Camarillo, Calif., a predominantly white suburb just outside of Los Angeles. As I struggled to immerse myself in already-cemented friend groups, comments alluding to my race alienated me even further.

One such encounter occurred during my first few weeks at my new school. A girl from my class decided to inform me during recess that I had a “mustache” and that was a decidedly gross thing to have as a girl. Before that interaction, I had never considered my facial hair abnormal or thought about my facial hair at all. But almost overnight, I became a scrupulous critic of my physical appearance, noting all the characteristics that set me apart from my classmates — the long and prominent hairs on my arms and legs, the length of my nose, my tan-prone skin.

Because I did not look like the people around me, these normal, innocuous parts of who I am became the parts I hated most. When I came home from school, that feeling of “otherness” was reinforced by the fact that I didn’t see anyone on television that looked like me. Growing up South Asian in America, I seldom felt beautiful — let alone desirable. I projected my insecurities onto “One Day”; I struggled to embrace Mod as Emma because I could not see myself as Emma either.

On-screen representation

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Indian Americans are now the largest sub-group of Asians in the U.S., growing over 50% from 2010 to 2020. Other South Asian groups, including Nepalis, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis, have shown similar or greater growth rates in the past decade. With an increasing South Asian presence in the U.S., it becomes even more critical that younger generations can see themselves reflected positively in Western media. Successful representation serves one or more of the following purposes: legitimization and humanization.

Representation can be a legitimizing force that reaffirms our right to belonging or validates our cultural experiences. “One Day” achieves the former as it effectively demystifies and normalizes South Asian immigrants, painting them and their descendants as articulate and nuanced persons who feel emotions, have agency and are just as deserving and capable of love as the next person. Mod’s portrayal of Emma steers away from overt cultural representation and instead builds on the qualities and experiences that liken her to her peers. Emma’s South Asian heritage, obvious only through the color of her skin, doesn’t dictate or inhibit her relationships, aspirations and self-worth. Her heritage is also not portrayed as an obstacle that she must overcome in order to be relatable to others. This offers a necessary contrast to stereotypes that assume the way we conduct our lives is oppressive, regressive or antithetical to the Western world. “One Day” shows us that our cultural identity doesn’t have to be the defining lens through which society views us, and it depicts an ideal world where South Asians no longer have to prove themselves worthy of society’s acceptance. We do belong, regardless of how much or how little of our cultural heritage we carry with us.

Now, that isn’t to say that good representation should avoid addressing the cultural aspects of our lives. In the young-adult Netflix show, “Never Have I Ever,” the main character Devi — portrayed by Maitreyi Ramakrishnan — has a character arc that simultaneously validates her experiences as an American teenager and a daughter of Indian immigrants. The show realistically depicts what a confluence of identities can look like for South Asians in the U.S. and desis elsewhere (“desi” is a colloquial term that refers to someone from the Indian subcontinent). The truth is that there is no perfect balance of identities and an inevitable struggle will ensue over how to integrate culture into our daily lives. Sometimes, Devi runs away from her heritage in order to assimilate;other times, she is unapologetically herself. In one episode, Devi offers a clever retort to someone who pokes fun at her mustache — a scenario that resonated with me and other desi girls watching. I didn’t relate to every single one of Devi’s desi experiences, and that is also okay! South Asian identity in the West is a spectrum of cultural assimilation, so our quest for diversity on screen should reflect the diversity of our experiences. And, by refraining from making our culture and heritage the only facets of our identity, shows like “One Day” and “Never Have I Ever” fold us into the mainstream dialogue, legitimizing our place in society.

In the broader social context, representation humanizes us when others don’t. In both domestic and international conflicts today, our nation readily extends its empathy to those indicative of the white diaspora and easily reduces others — brown people in particular — to mere statistics. Whereas traditional media coverage of these conflicts still perpetuates stereotypes, the new era of on-screen representation rejects the harmful notions that we are homogenous, dangerous or less deserving of empathy. This, in turn, re-shapes how we examine conflict narratives abroad and on a personal level, helps us overcome the cultural biases that constrain the relationships we build with those around us — especially those of South Asian descent.

In short, on-screen representation is a powerful tool for bolstering acceptance and breaking down biases built by decades of ingrained stereotypes that continue to circulate across media platforms.

Beyond the screen

On-screen representation shows us that we are worthy of being seen and understood outside of our cultural communities. It is also a fertile ground for lasting societal change. After all, film and television is a reflection of society and feeds off of our desire for social progress. Its impact trickles beyond the screen into other spaces where South Asian voices are marginalized or underrepresented.

Even at a relatively diverse institution like Vanderbilt, we are at a critical juncture for South Asian representation. SACE is one of the largest student organizations on campus, but it exists only in the context of multicultural awareness. South Asians are still struggling to break into traditionally white-dominated spaces on campus like Greek life. All of this circles back to representation. Until we are conditioned to accept historically and presently marginalized communities as part of the norm, we won’t see much change in the composition of Greek life at Vanderbilt or the makeup of other institutions where we lack representation — like the hallowed halls of Congress.

We are, however, moving in the right direction. In the 118th Congress, there are 21 elected leaders of Asian, South Asian or Pacific Islander ancestry. 40 years ago, there were only five — none of whom were female or South Asian. Take note, Greek life.

I think it’s safe to say that South Asian representation on and off-screen is not where it should be, but it is gradually getting there. “It won’t always be like this,” Emma says in the final episode, and she’s right. One day, South Asian representation will be enough — pun intended. We’ll know that day has come when we stop feeling like footnotes in the stories that unfold around us and no longer hesitate to believe that we can be the main characters we grew up wishing we could see.

Henry • Apr 14, 2024 at 10:01 pm CDT

This is a great article! I love how you connected your experiences to popular TV shows and the impact entertainment has on children everywhere, especially those with of a different race and cultural identity.

fellow south asian • Apr 14, 2024 at 12:40 pm CDT

bravo! an eloquently written piece that articulates exactly why representation has a broader impact than one might realize!