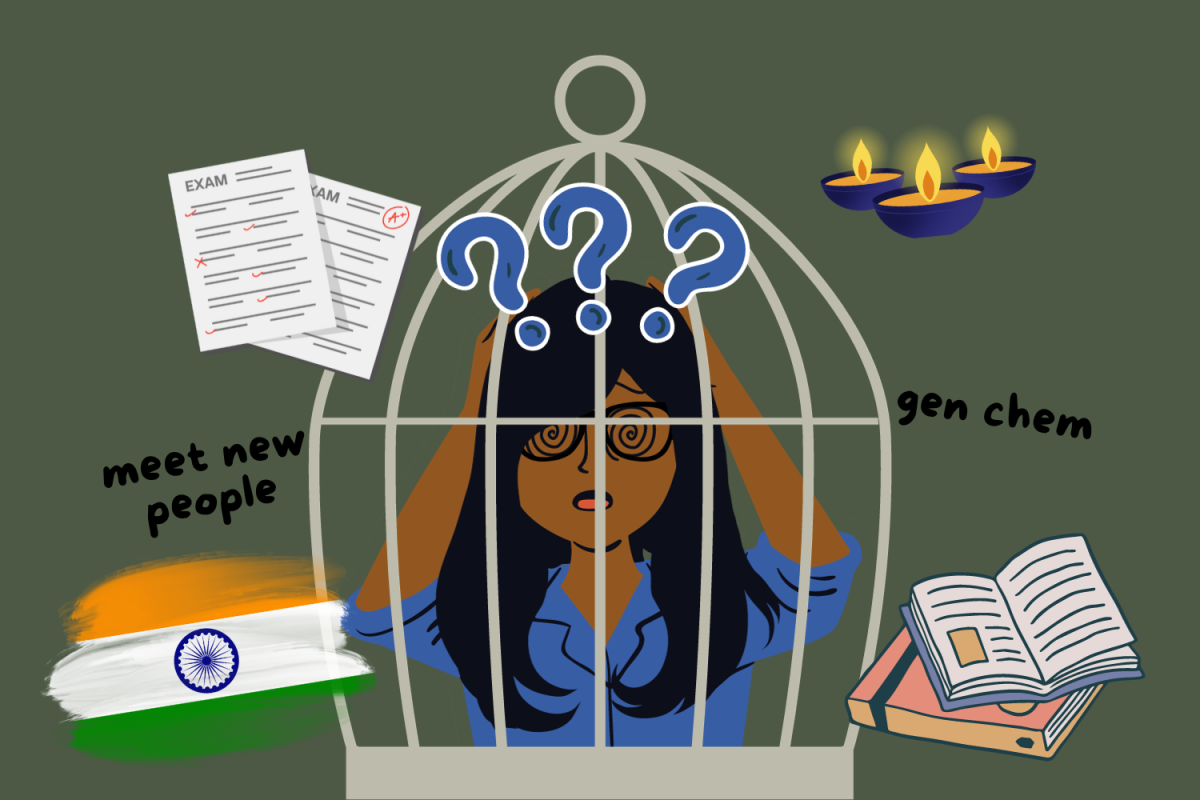

Growing up, I had trouble finding a perfect balance when navigating my racial identity. I found myself living a double life — one where I was oscillating between racial groups and feeling internal and external pressures to choose a side.

My race has been questioned by those around me, and I am no stranger to comments that I am too white to be mixed. I was either told that I don’t act like I am mixed or that I don’t act like I am Black. I didn’t know how I was supposed to “act my race” or show that I was connected to both cultures. It’s been difficult to balance what it means to be biracial and to navigate my racial identity throughout my life, especially here at Vanderbilt.

I often internalize how society perceives me and how others praise or take notice of my racial identity. When one race or culture is constantly the topic of discussion while the other is noticed inconsistently, it makes it seem as if that part of my identity is not even recognized, making it harder to truly connect. I’ve struggled to navigate embracing myself as a whole individual rather than having multiple disparate identities and having to code switch or act differently around different people. I have always felt stuck at the intersection of my identity, not knowing where to go next or where I belonged. Once I recognized how much emphasis I placed on others’ opinions, I was finally able to let go of my double life and embrace my racial identity. I now recognize how much I mistakenly valued other people’s opinions about my own racial identity in the past and how I continue to do so today.

Growing up as a Black and white biracial woman, I have realized that I cannot please everyone: not with my opinions, not with my behavior and not with my racial identity. I coped with this through code switching — manipulating my behavior or speech in the context of fitting into different groups. Code switching is usually done when you feel the need to belong to a group. I don’t always code switch with the intention of making myself more comfortable, but rather typically with the intention of doing it so others feel comfortable and therefore accept me.

When I started college, I was not sure if coming to Vanderbilt would help these feelings or cause more doubt about my racial identity and my sense of belonging. Leaving home to be in a completely new environment was terrifying, and I was not sure if I would fit in or be accepted. I pushed these doubts to the back of my mind, feeling optimistic for a fresh start.

However, since being here, my anxiety surrounding my racial identity has not gotten better. I still stand at an intersection trying to figure out where I actually belong and feel accepted. It can be a struggle to find where you belong when such a small percentage of Vanderbilt’s student body identifies as Black or mixed. I have anxiety going to Black events on campus because some people may not recognize that part of my racial identity. However, I also have anxiety when I don’t go to these events because it may seem as if I don’t recognize or appreciate my racial identity. While my internal conflict over whether or not to attend a cultural event may not seem like a huge deal, the fear of not being accepted can be paralyzing.

I have faced racially-charged comments from both white and Black students, even in spaces designed to be accepting and supportive towards all identities. I’ve experienced backhanded comments and been privy to unnecessary conversations surrounding my identity. Even after seven months at Vanderbilt making every effort to find places to fit in, I find myself still not knowing where I belong.

My Vanderbilt experience has not been all bad; I have found people who have accepted me for who I am and recognized me for both of my racial identities. I have learned a lot more about myself and how to combat any backlash or comments I receive. I don’t feel as uncomfortable if someone questions my identity because I have learned to trust myself and not be tethered to other people’s validation. After coming to these realizations, I have become more confident living in my own skin and embracing my biracial identity. I have learned that it’s not my responsibility to constantly explain myself in order to get other people’s approval. I have realized that I am the only one who gets to determine my identity — and it doesn’t matter how others perceive or judge me.

However, despite these revelations, it remains difficult to put this into practice. I can’t tell whether I truly stopped living this double life or whether I simply learned to cope with it.

Although I have been proactive and resourceful in finding the organizations and communities that accept me for who I am, the larger issue still stands: the communities that are intended to be inclusive need to address aspects that leave people questioning if they truly belong. There is a larger issue that needs to be addressed by both Black and non-POC members of the community. Going to a predominantly white institution is not the only obstacle when finding cultural groups where you feel accepted. In addition to the limited number of cultural organizations, an added barrier arises when you don’t fit the stereotype of the inevitable cliques within these organizations, leaving you as an outsider. When attending cultural events, I fear that my racial identity will not be recognized. From conversations with my other POC friends, I realized that there is a common feeling of not being the “correct type” of Black to fit in these spaces. The communities that were made to embrace inclusion still have exclusivity within them.

As a multiracial person, I sometimes feel like there is no solution. If you do rush a white sorority, then you get questioned or tokenized. If you decide to participate in Divine 9, then you get questioned. If you don’t decide to then you get questioned or disregarded.

On the other hand, feeling unaccepted in cultural organizations does not necessarily mean cultivating relationships with the non-POC side of the community is any easier. Sometimes it is harder to build these relationships if you do not share any common experiences. There is a constant fear that you may have to educate them on certain things or experiences because they will never live through them. There is also the ever-present tendency to constantly suppress your opinions, which can be draining. There will inevitably be cliques, leaving you as an outsider once again.

Racism and discrimination is still an issue faced by the Black community and the Vanderbilt community at large. More conversations surrounding race and identity need to be encouraged on campus. There should be more spaces that invite safe and informative conversations regarding different racial backgrounds and identities. Within cultural spaces, there should be more opportunities to engage in nuanced discussions regarding racial identity and its role in personal growth and development. Cultural spaces such as the BCC are highly valuable to the Vanderbilt community, and by giving a platform for difficult conversations surrounding racial differences, it will contribute to a collective effort that creates a more accepting environment for identifying students.

Being at Vanderbilt has taught me how to survive and thrive as someone who doesn’t always know where they belong. At a certain point, you have to stop caring about other people’s opinions. Not caring about how you are perceived is far easier said than done — sometimes it can actually feel impossible. I have not fully mastered the act of not caring, but I have noticed that the people I surround myself with have a major impact on how I feel internally. I have made a concerted effort to surround myself with people who don’t comment about my race or question who I am or what identity I hold. I have focused on finding friends who share common interests with me; finding a community through Vanderbilt Visions and My Commons Life has allowed me to develop a sense of belonging that is not dependent on my identity. Even if people don’t acknowledge your full identity, it does not mean it’s not a part of you. I have felt like a racial imposter for too long due to other people’s perceptions of me.

To any other Vanderbilt students struggling to reconcile multiple identities, I see you. Know that other people’s evaluation of your identity does not matter. You shouldn’t have to change who you are or act differently just to be accepted. When discussing your identity, you have to stand your ground. You can correct people — but don’t argue. Outside appearance is not the only thing that defines your racial identity. Rather, your lived experiences and the values that you hold dear ultimately define your identity — and that is not debatable.

Growing up and going to college has taught me one of the most important lessons I’ve learned: my race is a part of me, but it does not define me. In order to live the life that I deserve, I cannot focus on the opinions that others have about me and allow them to direct the trajectory of my life. Being a Vanderbilt student has forced me to confront aspects of my racial identity more frequently and more thoughtfully, which ultimately allowed me to gain a greater sense of self.

Shannon Hoelscher • Apr 5, 2024 at 9:36 am CDT

Exceptional article. Immense strength is required to share on this level. Thanks for taking the time to reflect outward!

Bri Woods • Mar 24, 2024 at 12:59 pm CDT

very thoughtful and well written.