Michael Knowles, a popular right-wing political commentator for The Daily Wire, spoke at Vanderbilt last semester on Nov. 28, 2023. Knowles’ pro-colonialism speech and his previous statement that “transgenderism must be eradicated” sparked protests during the talk and calls for the university to prevent similar speakers from coming to campus in the future. I disagree with Knowles’ views, and I even challenged him during the Q&A portion of his speaker event. But I also disagree with the protestors who believe Vanderbilt should disinvite public figures like Knowles from speaking on campus again.

A university should educate and provide a community for students. To educate means to provide a student the necessary skills needed to excel in their chosen career path and teach them how to think critically. In other words, education should teach people both what to think and how to think.

Thinking critically means determining whether people’s claims align with evidence or are logically consistent. This skill is exercised when engaging with new ideas — especially moral ideas.

The backlash against Knowles tells us an important thing about free speech on campus: students seem more interested in regulating moral speech (such as abortion and gender affirmative care) compared to non-moral speech (such as economics or infrastructure).

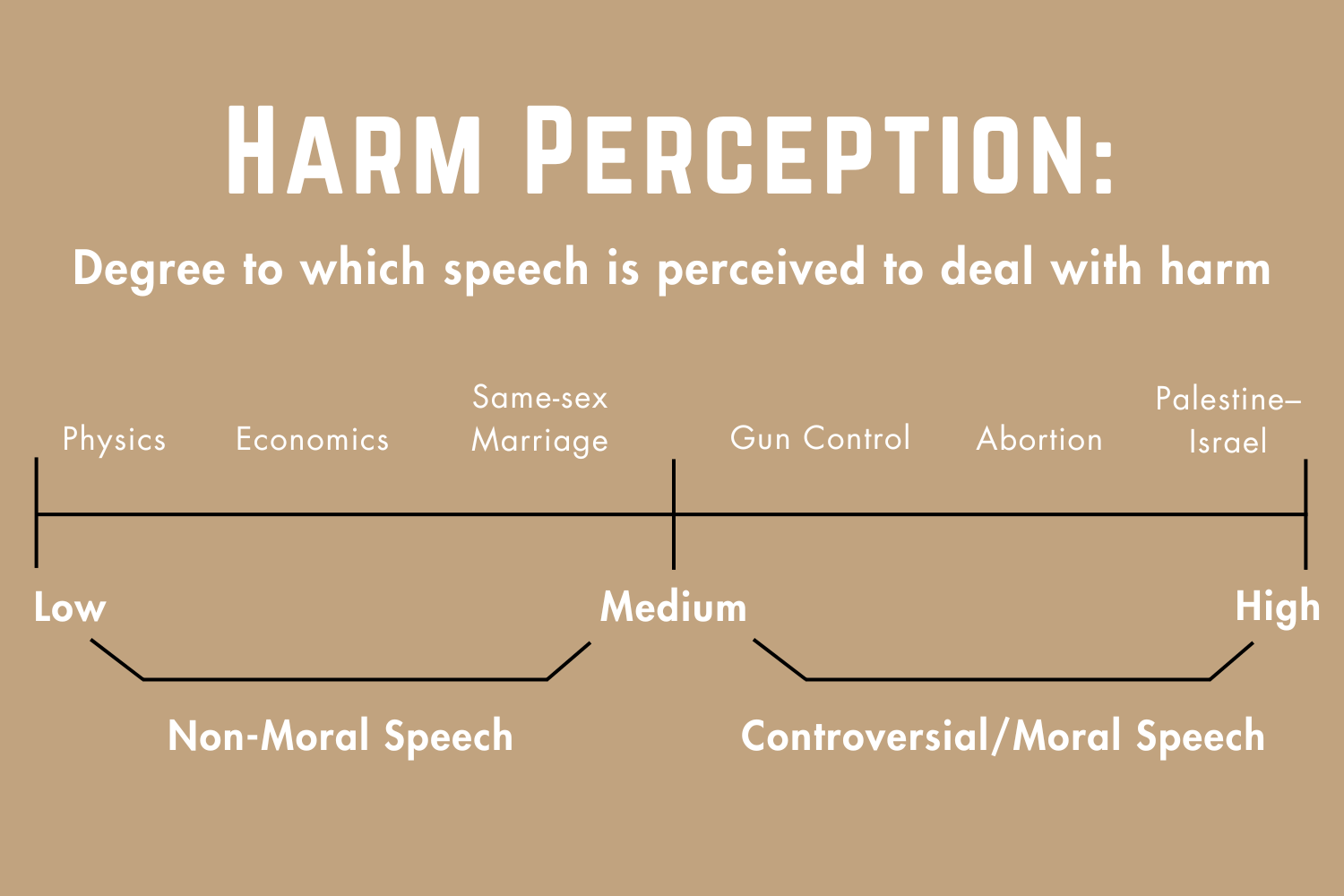

According to a 2017 study, 93% of college students are in favor of inviting guest speakers with diverse viewpoints. Students in the U.S. typically have more reasons to protest speakers when moral speech is involved. What distinguishes moral speech from non-moral speech is the degree to which speech is perceived to deal with harm to a group of peoples’ physical state, emotional state or dignity. As shown in the figure below, based on the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, topics like economics and physics are not viewed as controversial as abortion or gun control. Internet search trends from March of 2024 show that some of the most morally charged topics in the U.S. today are the Israel-Palestine conflict, abortion and gender-affirming care.

What societies consider as moral speech changes over time, though. In 2004, Gallup found that 60% of Americans opposed same-sex marriage. Now, it finds that over 60% approve of it. The question people are concerned with is not if we should allow free speech but free moral speech.

Should we have campus speakers who take different stances on today’s controversial topics?

Many who say “yes” believe engaging with moral speech requires stronger critical thinking than non-moral speech due to the topics’ complexity and urgency. Adequate education should allow a student to evaluate the evidence or logical consistency of claims related to tough topics like morality. Analyzing moral speech is a way for students to think more rationally by evaluating their views as distinct from their identity. Additionally, there is potential to modify our moral ideas in ways that can help reduce harm. If we hosted civil debates between influential pro-Palestinians and Zionists on campus, perhaps we would come to a better solution to the lives lost in the Middle East.

On the other hand, many who argue that we should not allow moral speech on campuses say that this policy inevitably allows immoral speech. Immoral speech can then lead to harmful thoughts and behavior toward others. This position assumes that once somebody has achieved “correct” moral judgment — such as respecting transgender people — listening to speakers of the opposite side will taint the judgment and can lead to harmful behavior, such as bullying trans people. Additionally, those who already hold hateful views double down. As a result, people attempt to regulate the speech of those who they believe hold immoral views.

In this article, I will evaluate the weaknesses of both views and determine whether allowing or preventing diverse moral speech is more beneficial to a university’s goal.

Caveats for allowing moral speech

The first caveat for allowing diverse moral speech is that it can lead to violence. However, I have yet to see examples illustrating the content of a speaker’s words on a campus resulting in violence. We have, however, seen violence such as assault on students and holding faculty hostage committed to prevent a speaker from visiting college campuses. Even then, only 5% of students support using violence to stop speech. Encouraging civil, non-violent protest through culture and policy can prevent this attitude. Vanderbilt defines civil discourse as speech “that demonstrates respect” for contrary opinions. Without civility, moral discourse becomes unproductive and dangerous.

The second caveat is that allowing moral speech on campus does not ensure diverse moral speech. Recently, there has been better advertising for conservative speakers compared to liberal speakers on campus. While everyone knows about the Michael Knowles and Liz Cheney events, not many have heard about Tarana Burke speaking. The left at Vanderbilt needs to advocate for their speaker events better. And if not that, at least challenge these conservative speakers civilly. Without these actions, we are left with only one side represented.

The third caveat is that diverse moral speech always challenges peoples’ moral views and, therefore, their core identity, which can make them feel uncomfortable. Feeling unwelcome in a dialogue can lead people to exclude themselves from conversations, causing a decrease in diverse people in the dialogue. As Vanderbilt senior and Indigenous peoples’ rights activist Katey Parham claims, Indigenous peoples on campus feel unsafe as a result of Knowles’ argument about the benefits of colonialism. There is no true antidote to preventing this situation of harm. The best that can be done is ensuring no person is ever forced to change their moral views.

In extreme cases, moral speech challenging identities can also lead to a person engaging in self-degradation and self-harm. This can be avoided through better mental health resources and outreach on campus that teach people to deal with attacks to identity.

Caveats for preventing moral speech

Those who believe diverse moral speech should not be tolerated do so because it allows “immoral” speech. Yet, it is hard to prove who is morally “right” or “wrong” in most moral scenarios. You may hold a pro-Palestine or pro-Israel position, for example, but it is wrong to assume that you have the complete moral picture of this complex situation.

Speech regulations on college campuses ultimately lead to a decrease in educational value by reducing opportunities for students to think critically about controversial topics. There is no antidote to this caveat.

Remaining caveats for allowing and preventing moral speech

Both positions on free speech on college campuses have problems that lack clear solutions. Which is worse: a reduction in the voices included in the dialogue (diversity) or a reduction in critical dialogue (education)?

To me, the reduction in critical thinking by regulating moral speech is a worse caveat than potential decreases in diversity. In fact, moral speech does not need to lead to reduced diversity. People who feel uncomfortable from a moral view that challenges theirs can choose to involve themselves in the dialogue more, not less. Knowles challenged my Islamic identity, and I chose to voice my views against Christian nationalism to him. Moreover, students will eventually have to deal with moral speech upon graduating, and it is better to be prepared for that experience.

Speech regulations on college campuses ultimately lead to a decrease in educational value by reducing opportunities for students to think critically about controversial topics. It is difficult for me to say definitively what is right or wrong for many moral issues. When I do hold a strong belief, I want to listen to those who disagree with me and civilly challenge them. When I pressed Knowles on his Christian nationalism sympathies, my views did not change; in fact, they became more coherent as a result of his scrutiny. I was forced to think about Islam as distinct from my identity as a result of his critiques of the religion. I even modified my views of American colonialism, conceding that it’s difficult to define the colonizer given that Indigenous peoples in the U.S. took land from each other as the colonists had done. That’s education.

Vanderbilt should continue to allow free moral speech among its speakers and community members. Diverse moral speech allows students to think critically about controversial ideas — a mark of an adequate education. Members of the university should engage in conversations civilly or else they lose their educational value and can be harmful. Vanderbilt’s liberal students must advocate for their speakers and challenge conservative speakers civilly, rather than heckle unproductively. Finally, knowing that moral views can be central to people’s identities, no one should be forced to challenge these beliefs. But for those who want to do so, let’s keep providing that opportunity.

If college campuses can’t discuss the different ways in which we should deal with the death of the innocent, the rights of the oppressed and the degradation of human dignity, then where will we? In a place of religious gathering? In the Senate? On social media? Hardly. A university that allows diverse and challenging discourse can become a unique asset to society. It will require daring, but we’re no strangers to that.