As a first-year student, I penned an article about my frustrations with the housing process. I expressed my disappointment of how the university structured their room assignment system and my exhaustion from applying in multiple rounds of the housing process — just to learn later that no first-years were successful in those processes anyways.

At the time, I thought I was writing about an issue specific to first-years. Given Vanderbilt’s seniority-driven lottery system for housing, it made sense that the newest students would face the greatest challenges in the housing process. Surely when I had a better spot in the lottery, the process would become less painful.

I was wrong. My frustrations persisted year after year. As I enter my final housing assignment process at Vanderbilt University, I am more disheartened than ever.

Too many housing processes

Under Vanderbilt’s seniority-driven lottery system, each student is assigned a point value according to their grade level: two points for rising sophomores, three points for rising juniors and four points for rising seniors. Students then apply in different room selection processes either by themselves or with a roommate group. A lottery drawing takes place, giving preference to students or groups with higher average point values. If students are successful in the lottery, they then get to choose their room.

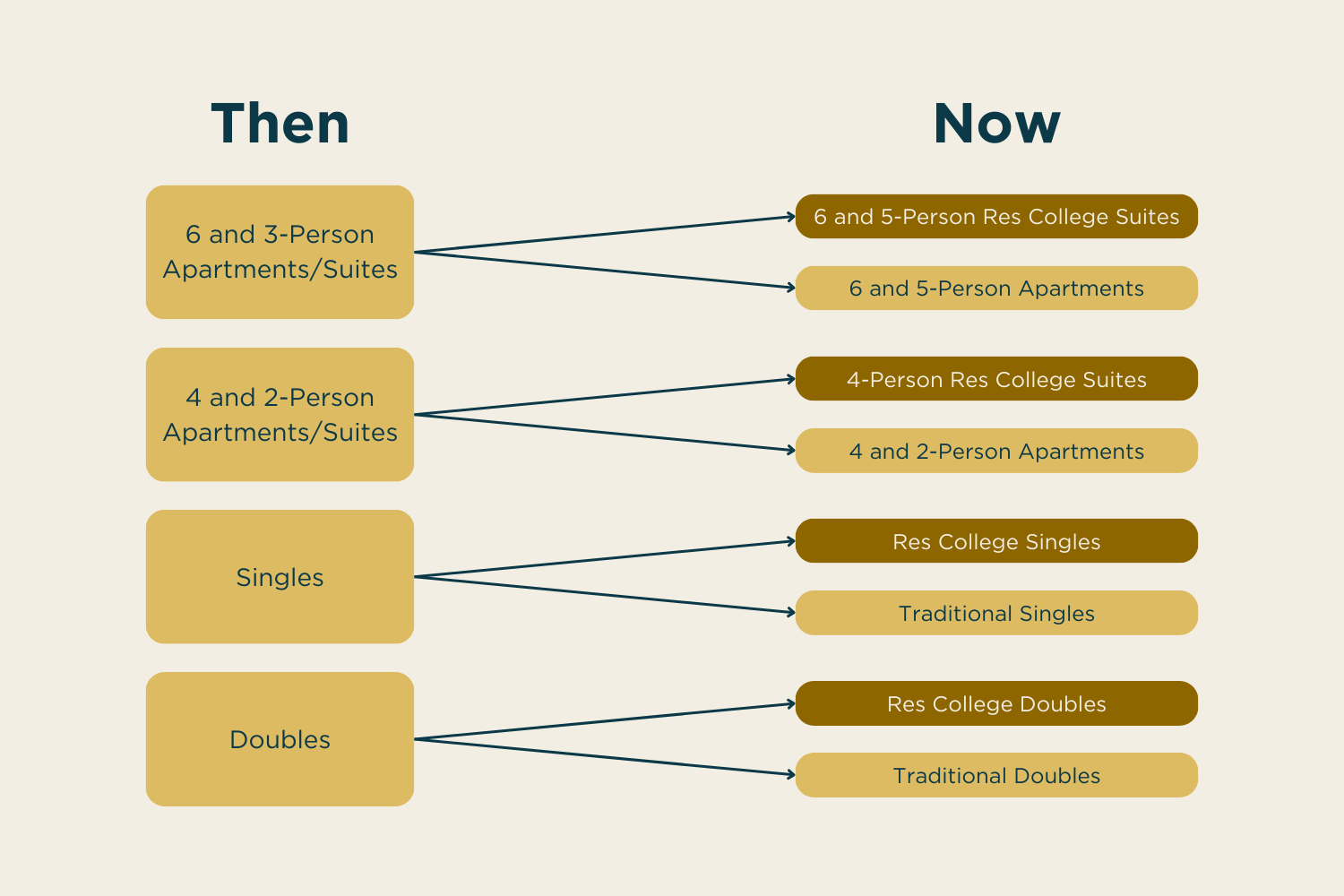

When I first applied for housing for the 2022-23 school year, there were four main selection processes: 6 & 3-Person Suites/Apartments, 4 & 2-Person Suites/Apartments, Singles, and Doubles.

Sofia El-Shammaa)

Since the 2022-23 housing process, the number of these sub-processes has doubled, with the university dividing each sub-process into a residential college and a non-residential college process. This change exacerbates one of the main problems; first-years are applying in more processes in which they most likely have zero chance of being successful. Last year, no individual or group with rising sophomore status was successful in five out of the eight processes. Having students take on this futile endeavor week after week with zero chance of success is mentally draining and unnecessary. It just creates false hope, wastes their time and ends in disappointment.

Room selection and personal preference

The fundamental problem with the housing process is its rigidity: once a process is over, there is no changing anything. If you’ve accepted a room, you may not trade it in for something better, and if you reject a room, you may not get it back later in the process. It is possible to request housing assignment changes after the main process is over, but that process is difficult and requires some luck to be successful. Because of how the system is structured, accepting a room that isn’t your first choice may be preferable to rolling the dice in another process — you might end up with something worse if that gamble doesn’t pay off.

This framework results in an incentive structure that encourages students to accept rooms earlier in the process. A problem arises when a student’s preferences don’t align with the process order the university has created. They are then faced with the dilemma of whether to play it safe with an earlier process or risk it in a later process in hopes of getting their top choice room.

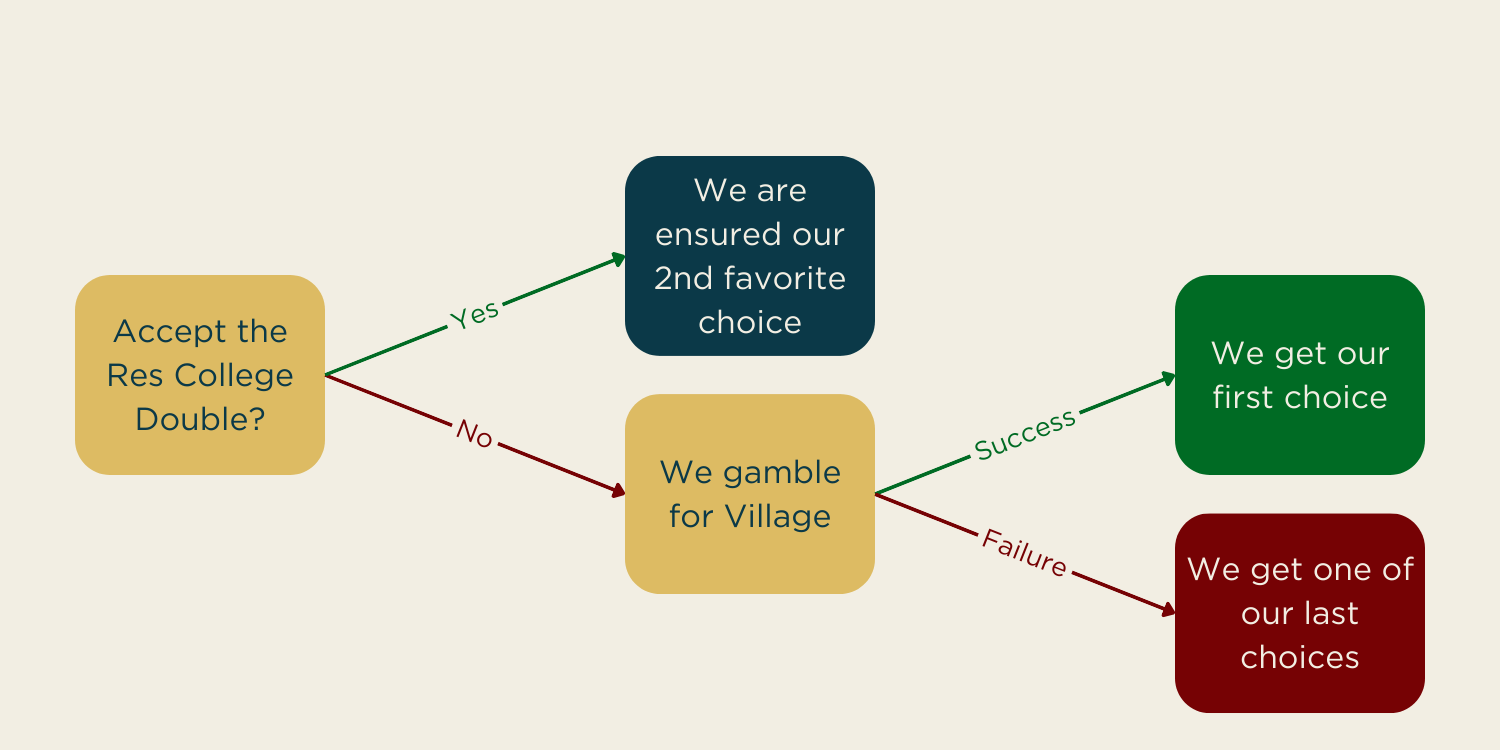

My roommate and I were faced with this dilemma last year. Our top choice for housing was a two-person apartment at the Village at Vanderbilt because of its amenities and proximity to my classes on Peabody. After that, our order of preference was a double room in a Residential College, followed by a two-person Highland Apartment. We wanted to avoid traditional doubles at all costs, we didn’t want single rooms and we didn’t have any other roommates.

The problem we faced was that the selection process for our second choice, a residential college double, came before our first choice, a Village apartment. This meant that if we waited for the 2-Person Apartment process but failed to secure a Village apartment, then we’d lose out on the opportunity to apply for a residential college double and we would automatically be subjected to our least preferred choices. On the other hand, if we accepted a residential college double, we’d protect ourselves from our least preferred options — but sacrifice our top choice.

(Sofia El-Shammaa)

My roommate and I are risk-averse, which means we opted to play it safe and accept a residential college double. In hindsight, it was the wrong decision. Looking at the data from last year’s housing process, I’m fairly confident we would have gotten that Village apartment had we waited for that process. However, as much as I want to kick myself for making the “wrong” choice, I had no way of knowing that at the time. The housing process had just been reordered, so there wasn’t clear data on who would be successful in which processes. Even with previous data, there is no way to confirm which groups of students will attempt which housing processes until after the process is over.

Many students face this dilemma because room preferences will vary from person to person. Each of us places different values on factors such as location, building age, room amenities and number of roommates, so it makes sense that we would all have different preferences on housing. The problem is that unless a student’s preferences align with the order of the housing process, they’re going to face the difficult decision of whether to pick the safer choice — whatever that may mean for them — or risk it for what they really want. It’s a tough decision, and the repercussions will last a full year.

Roommate Group Selection

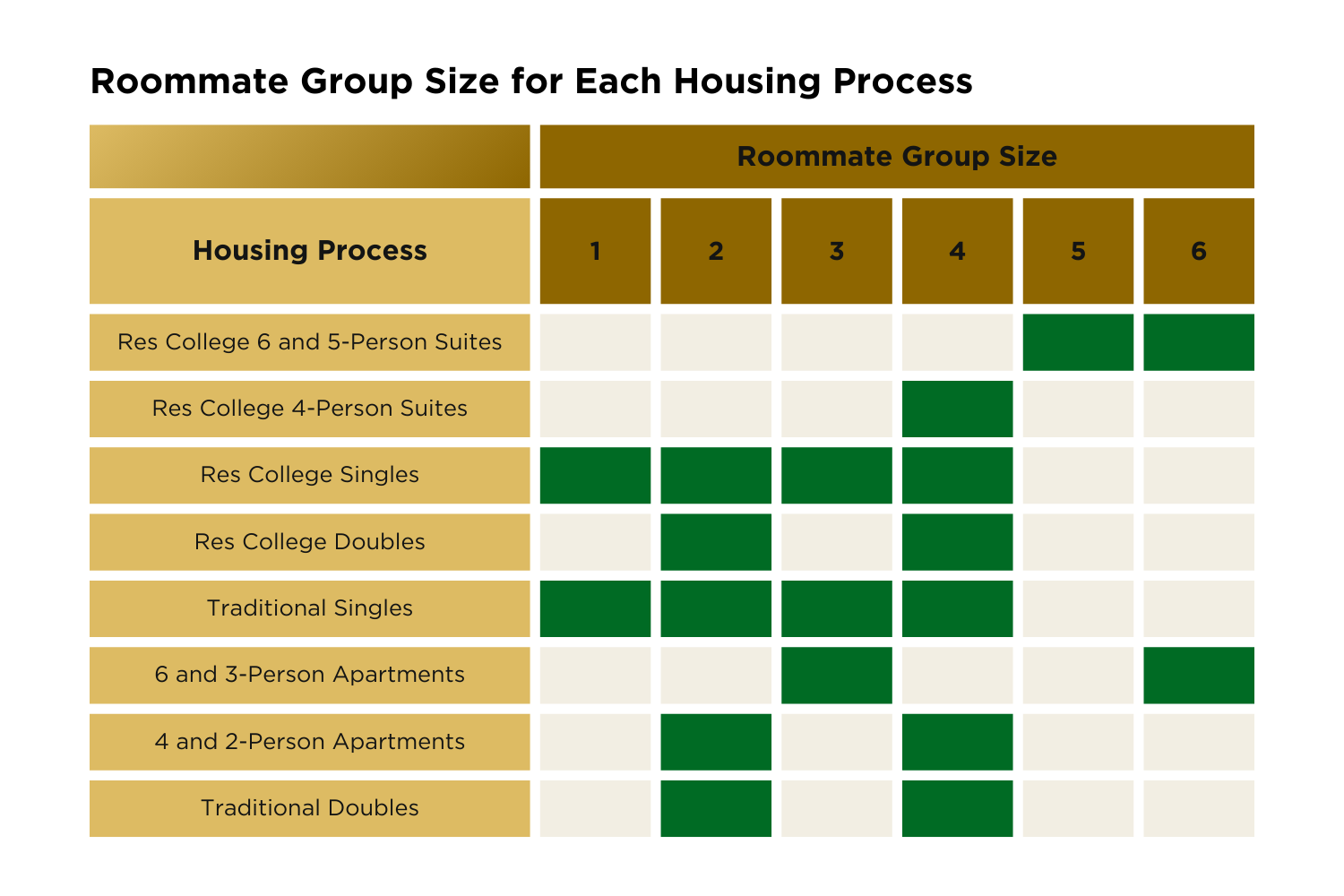

Another headache comes from the formation of roommate groups, which is required for all housing processes except for single rooms. However, breaking the process into multiple rounds — each with a different number of roommates — puts a massive burden on students. This is because they have to form roommate groups not only with the current round in mind, but also with the possibilities of changing group size for future rounds.

(Sofia El-Shammaa)

Last year, my roommate and I tried to find a third roommate so we could try for a three-person Village townhouse as well as a two-person Village apartment; however, no one wanted to join us because of what would happen if we were unsuccessful. The only two processes that follow the three-person apartments are two-person apartments and traditional doubles — both of which require roommate pairs. Anyone that joined my roommate and I would be left on their own if we didn’t secure a three-person apartment as we would stay partnered together for future processes that required an even number of roommates.

This problem wasn’t specific to that situation either. This year, I tried over a dozen different combinations of roommates to form a four-person suite, but because everyone had to look out for themselves and plan strategically, all but one combination collapsed. The worst part was that the guiding priority of these roommate decisions was strategy, not necessarily choosing the people we most wanted to room with.

Much of the chaos and exhaustion of the housing process comes from the ever-shifting game of roommate mathematics. If we try for a six-person suite, which two are excluded in the next round if we have to try again for a four-person? Do I ditch the person I most prefer to live with if someone else offers me a spot that completes their group? The result is a level of alliance formation and disbandment that rivals a season of Survivor.

The alternative

At a glance, one can appreciate how housing has ordered the selections; with campus sentiment that residential colleges are the best housing, it makes sense that Vanderbilt would put those at the start of the process. However, the current system fails to account for the fact that everyone has their own preferences when it comes to housing. Because preferences will vary, there is no singular order that will please everyone: if we reordered the processes to match my preferences, someone else would be put in a tough spot. Instead, Vanderbilt should eliminate the ordering altogether and restructure the housing assignments into a single process.

Under this proposed system, students would still form roommate groups and their points would be averaged. Then, as usual, housing will conduct the lottery and assign everyone a time. At their assigned times, students would select the room or rooms they want (once again, as they normally do). The only difference between the current system and the one I’m proposing is that under the proposed system, all rooms would be available at the same time. Students can select any style of room they’d like, so if no apartments remain, students could go for singles, doubles or whatever room style remains that would be their next favorite choice. Groups could even mix and match room styles based on what their members want. Everyone would get their top preference of what’s available because all room would be available for selection in a single process.

This adjustment would fix many of the problems with the current system. Underclassmen wouldn’t get dragged through several processes they never had a chance of success in. There’d be no more pressure to choose between applying in your preferred processes that could all end in failure or playing it safe and ending up in a dorm you didn’t want. Roommate groups wouldn’t collapse after each process, meaning that students can pick the roommates they most want without concern of abandonment or conflict. Restructuring could even shorten the housing assignment process from two months to just a handful of days since the university wouldn’t have to run a new process every week.

The current housing assignment system cannot continue as is. Thankfully, this year will be my final time going through this disaster of a process. I truly hope that this is the last time everyone else has to deal with the stress and difficulties of the current system.

! Or have nothing left and be in housing that is the super far from all your classes and not even a choice you selected. (The shuttle, or lack of could be another hustler story!) The fact that some freshmen get the Hank hotel and great res college dorms as sophomore and upper class men lead me to believe the lottery is fixed!

! Or have nothing left and be in housing that is the super far from all your classes and not even a choice you selected. (The shuttle, or lack of could be another hustler story!) The fact that some freshmen get the Hank hotel and great res college dorms as sophomore and upper class men lead me to believe the lottery is fixed!