Crowded lecture halls, cramped residential living, long lines at Rand and Suzie’s cafe during rush hour — all of these have something in common for me: I struggle with them as an autistic student at Vanderbilt.

My autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis was a welcomed surprise during my sophomore year of college. I had willingly gone through testing with the hope of finding a reason for my shortcomings — academic or otherwise — but I did not expect the results to validate my daily experiences. While I only recently received an official diagnosis, I have spent all 19 years of my life living with ASD. My hidden internal conflict with neurodiversity left me jaded in a lot of ways that I still struggle to understand. One particular part of my day-to-day life was incredibly difficult: being a student. My experiences as a college student here have made it clear that Vanderbilt, despite its expressed support for neurodivergent people, is still incredibly inaccessible for autistic people.

I have to give some credit where credit is due. Vanderbilt’s accommodations are generous, especially with support for exams and housing offered with sufficient documentation. However, this very accommodation highlights a problem within itself: the requirement for students to present “sufficient documentation” to receive accommodations. Many students do not have the privilege or access to a formal diagnosis, yet formal diagnostic processes are required to use the accommodations available. In this way, the current system favors those who were diagnosed prior to entering university, which hurts people who did not have access to these resources or would have likely been dismissed due to stigma. Even at a research university with a vast network of mental health services, ASD diagnostic testing at the UCC has only recently become a covered cost under the student health fee, and the waitlist to begin testing can range for several months — in my experience, it was over a year. Prior to this change in coverage, I was quoted a minimum of $500 for a diagnosis at the UCC. In our current system, a first-year student with the hunch that they have autism may not receive testing until their sophomore year, limiting their ability to receive any accommodations until the end of that academic year at the earliest. The only alternative is to go outside the university system, which can cost thousands of dollars. Nashville Psych, the most common off-campus provider recommended by the UCC for students seeking diagnosis and treatment, charges a $2,100 diagnostic fee. Additionally, they are out-of-network providers, so insurance coverage may vary. The student health insurance under Aetna does not explicitly cover ASD testing in any capacity and has not during my entire college career. So, despite the wonderful accommodations available here, they are often not available to those who need them the most. At the very least, the university needs to address the supply and demand issue within the UCC so that students needing support stop falling through the cracks.

That being said, Vanderbilt is simply not built with autistic people in mind. Our newest residential college, Rothschild College, has one of the least sensory-friendly dining halls on campus. In an attempt to mimic the collegiate architecture of prestigious New England schools, they inadvertently constructed a disability nightmare. It’s one thing to discuss the physical space being hard to navigate for people with physical disabilities, yet even as an able-bodied person, it is simply an overwhelming space. My autistic friends and I cannot eat there without some sort of ear protection, as the ceilings are tall and echo sound with nothing to absorb it. The cramped seating arrangement also contributes to a lot of pushing and shoving, which is incredibly hard to handle.

Rush hour at any dining hall is a nightmare, but Rand Dining Hall and Suzie’s Food for Thought (Central Library) are particularly heinous culprits. In Rand, it is incredibly difficult to buy food without your personal space being invaded or getting pushed and shoved by other students, which can contribute to meltdowns for autistic people. Suzie’s gets so crowded that students wishing to buy food cannot all physically fit in the cafe at the same time — not to mention the constant noise from the baristas and patrons both struggling to be heard.

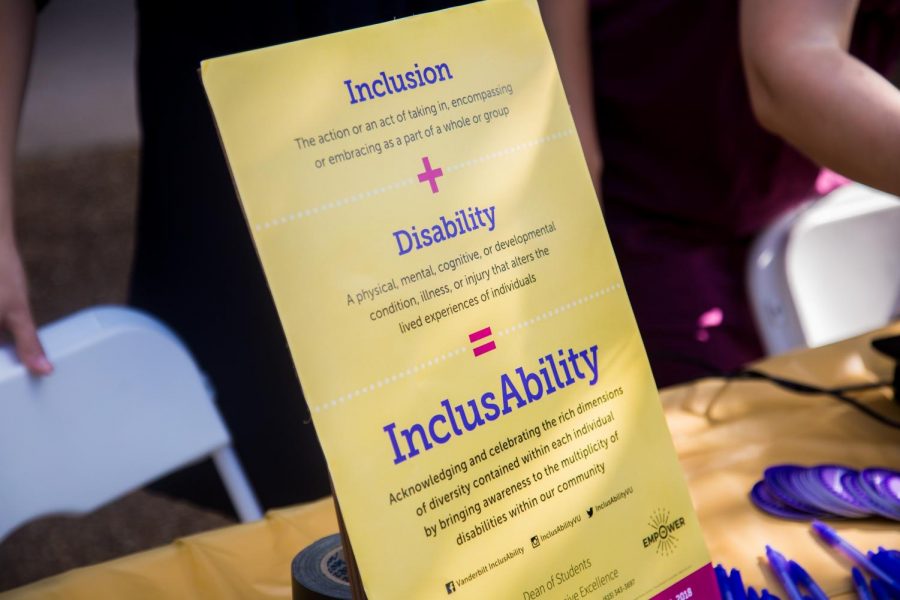

I believe that Vanderbilt wants to help neurodivergent students, whether it is those with ASD, ADHD or students struggling with anxiety and depression. The Student Care Network (SCN) was always more than helpful to hear my day-to-day concerns and connect me to alternative resources when on-campus options weren’t sufficient. Additionally, Student Access Services (SAS) offered accommodations where they could be given. The systemic framework is in place within the university to help autistic students, however, no amount of accommodation can possibly erase the negative effects of hostile architecture. So, what needs to change?

As it stands, every dining hall and most common spaces are not sensory-friendly. Realistically, space and noise are only regulated well in non-dining spaces, such as libraries or certain academic buildings like Buttrick Hall or Mayborn. While these spaces help in academic contexts, students at Vanderbilt need to be supported in living, dining and school spaces, and therefore spaces limited to academic buildings are not a real solution to the problem. At a university where on-campus living is a priority, every facet of daily life should be as accessible as possible. It would be well within Vanderbilt’s reach to have architecture in their newer buildings that prioritizes personal space and noise absorption without necessarily sacrificing aesthetics. Dining halls could have seating that accommodates single diners, similar to study booths in the libraries. This would provide a quieter section of the dining hall that is not overlapped by other students and is physically separate from the lines that sometimes bottleneck from the service areas. Architecturally, lower ceilings in new buildings or sound absorption pads in existing spaces would work wonders toward creating less noisy spaces for diners. Despite promising apps that show dining hall queue times, there are additional ways to revamp those technologies to be suited to the needs of neurodivergent students. A tool that tells students how noisy a dining hall may be at a particular time can help students with sensory needs to make informed choices. Similarly, lecture halls could have seating options for people who cannot sit shoulder-to-shoulder with other students, which would also benefit immunocompromised and physically disabled students. Generally, creating uncrowded and less noisy spaces would be beneficial to many students — not just those with autism.

As campus grows and changes with the addition of new residential colleges and massive renovations to existing facilities, Vanderbilt has the opportunity to be thoughtful about the students it serves. While certain additions, like the Mayborn/Magnolia connector building, make campus a more inclusive space, the inaccessibility of our newest residential college shows that Vanderbilt continues to choose aesthetic over functionality. However, Vanderbilt’s recent commitment to accessible academic policies demonstrates that the university wants to be inclusive, and it makes me hopeful for the future of inclusion on campus. However, I do not hesitate to say that hoping for sensory-friendly dining halls will be fruitless until Vanderbilt makes the conscious decision to reevaluate their architectural priorities.

Unless a place is carved for people like me, I will continue to sport my noise-canceling headphones to survive the lines at Rand — where I eat the same lunch every day — all to feel some sense of control and normalcy in a system that is not meant for me.