I applied to Vanderbilt because I wanted access to an amazing education and the opportunities that education would provide me. But college is much more than just academics. We study, socialize and reside here. Vanderbilt is not just a school; it’s a restaurant, grocery store, catering service, apartment complex, law enforcement agency, investment firm and more. Campus has so many sub-institutions that it is practically a small town. This system results in the university wielding immense power over its students.

Unfortunately, Vanderbilt has abused its monopoly power, forcing many students and their families to foot an unfair bill — especially with housing and dining.

Housing

Vanderbilt’s residential requirement mandates that all undergraduate students reside on campus for the entirety of their four years unless they receive explicit permission. Students are subject to whatever housing prices the university decides, and they have no other options without off-campus authorization.

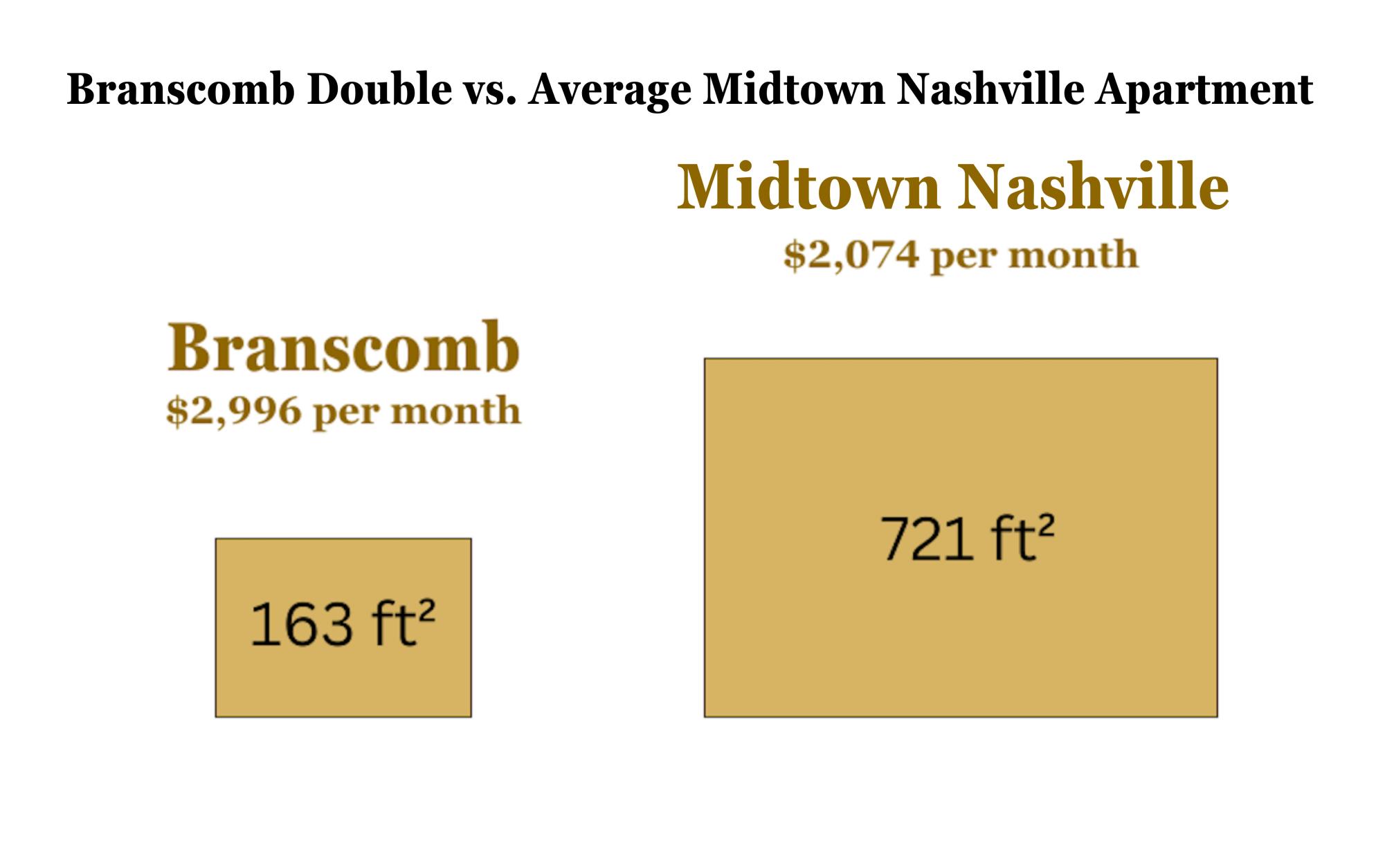

This year, housing costs $13,484 per student for the whole school year, which breaks down to $1,498 per month. This price does not change based on the size or type of room — such as singles or doubles — in which a student lives, except for a $412 semesterly residential college experience fee. If a student lives in a double — usually one room with two beds and no plumbing — both residents pay the same fee, meaning monthly rent is actually $2,996. Compared to the Midtown Nashville area average — which generally ranges from a studio through three-bedroom apartments — of $2,074 per month, it’s already clear that Vanderbilt is severely overcharging, but the story doesn’t end here.

In Midtown, the average apartment size is 721 square feet, meaning that the monthly rent is approximately $2.88 per square foot. Rooms at Vanderbilt look very different. Branscomb Quad rooms are a valuable comparison point because the doubles are standardized in size which allows for exact calculations. Additionally, the vast majority of Vanderbilt students live in a double at some point during their time at Vanderbilt. In Branscomb Quad, doubles are an average of 163 square feet, which means that monthly rent is $18.38 per square foot. This price disparity is even more atrocious when we take into account Midtown apartments’ additional amenities like bathrooms, full kitchens and separate bedrooms. While I admit there are benefits to living on campus — like connecting with people, having a shorter commute to class and housekeeping services in select rooms — it doesn’t warrant a 538% increase in rent in comparison to the area average.

Almost all first-years live in double or triple rooms, and many sophomores and juniors live in a double or a proportionately similar single, meaning many of us pay a similar rate for square footage. The situation is still bad for those living in the on-campus apartments and suites which have space and amenities more similar to a typical Midtown Nashville apartment. For those living in an on-campus apartment, the total cost is $4,500 or even $6,000 per month for three- and four-person, two-bedroom apartments. Residential college suites — which only place one student per room — also fall short as they only have a kitchenette, and four to six residents share a single bathroom. In comparison, many two-bedroom apartments in the area have multiple baths. In spite of these faults, suites cost about $6,000-$9,000 per month.

Vanderbilt’s price gouging is shameful. If Vanderbilt kept with the area averages per square foot per month, a Branscomb double would cost less than $500 per month. Split across two roommates, the total cost of housing for the whole school year should be under $2,200 per person living in a Branscomb double.

The university is taking advantage of its students, and it can only do this because students have no other housing options per the university’s own rules. Unlike the freedom most people have to change their living situation, we are trapped because our landlord has the power to ban us from living anywhere else. Even when a building floods, the hot water goes out or a dorm’s security systems fail, Vanderbilt students aren’t even allowed to look for an alternative. If we want to continue attending this university, we just have to keep paying more than six times the market rate and pray the water will warm up tomorrow.

Dining

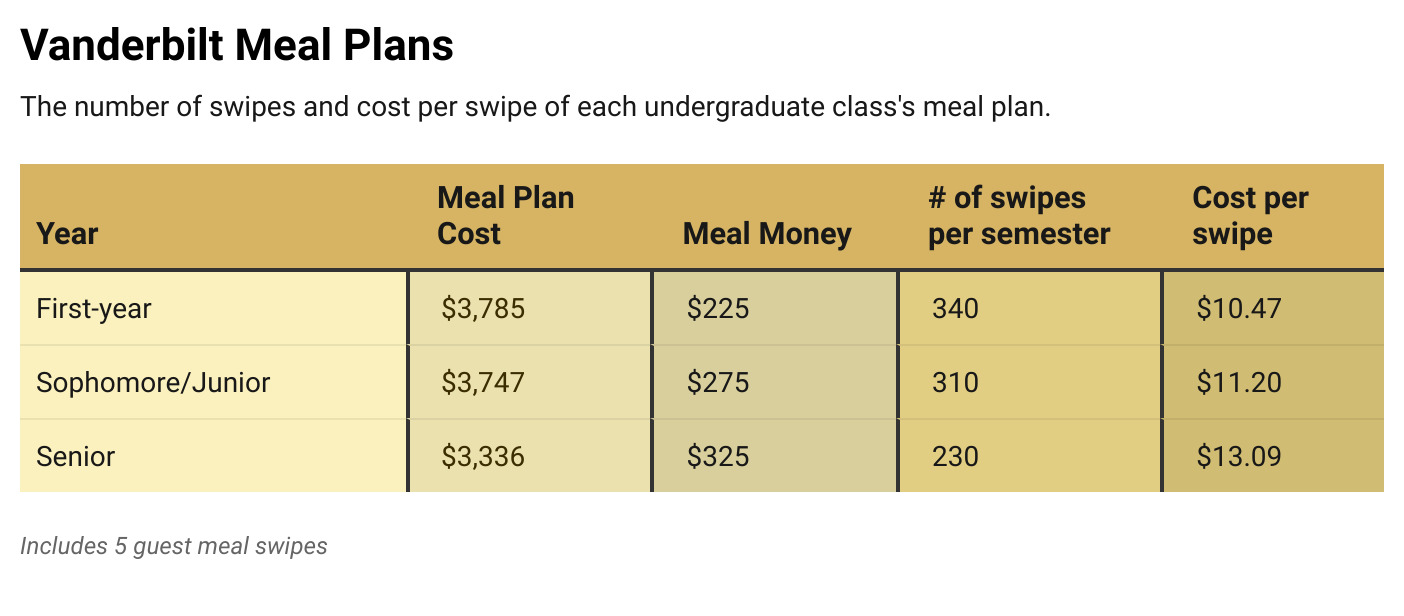

Another place where Vanderbilt’s monopoly power is on full display is in the dining halls. Vanderbilt Campus Dining requires students to purchase one of three different meal plans corresponding to grade level. When calculated on a per-swipe basis, first-years pay $10.47 per meal, sophomores and juniors pay $11.20 per meal and seniors pay $13.09 per meal.

Chloe Whalen)

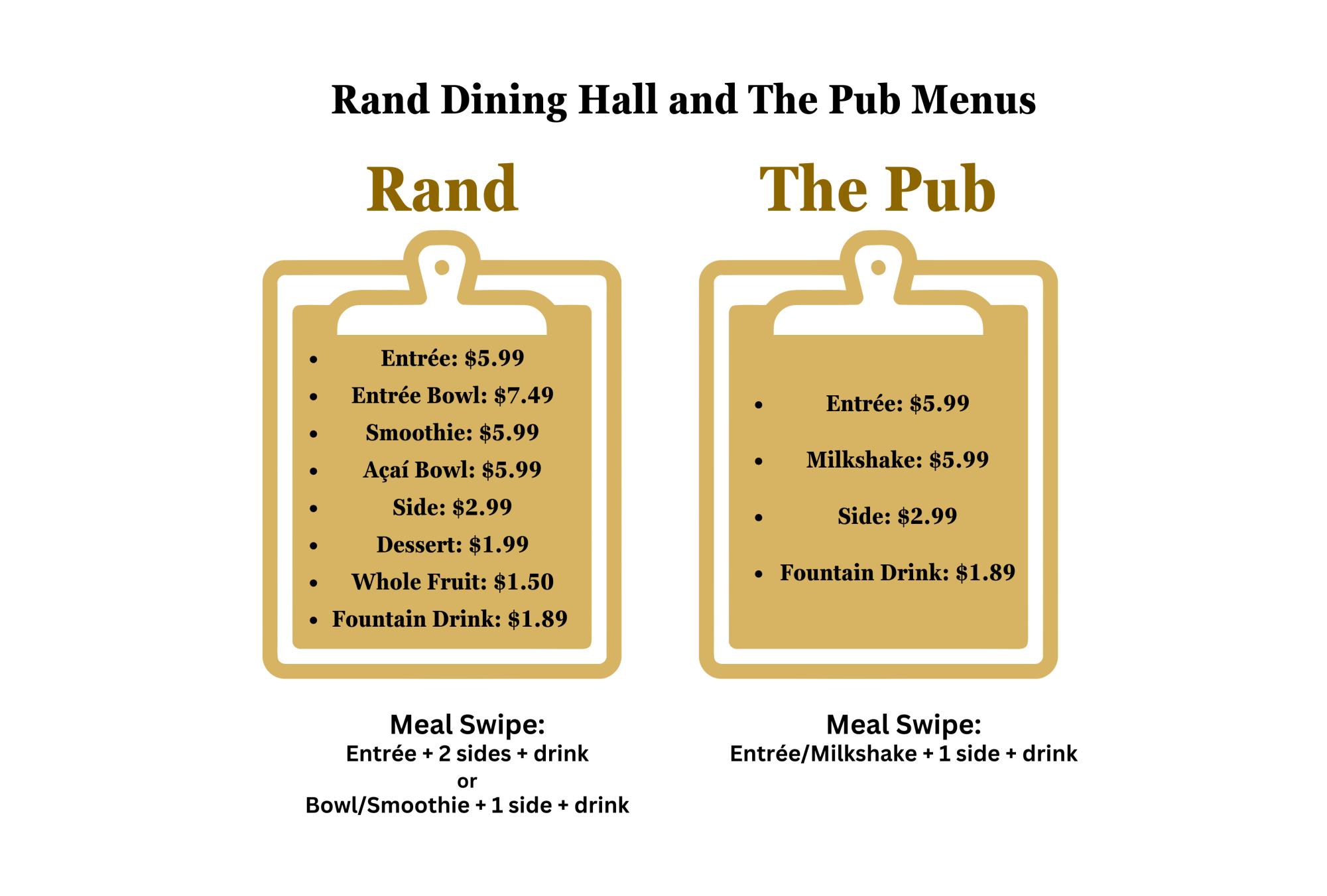

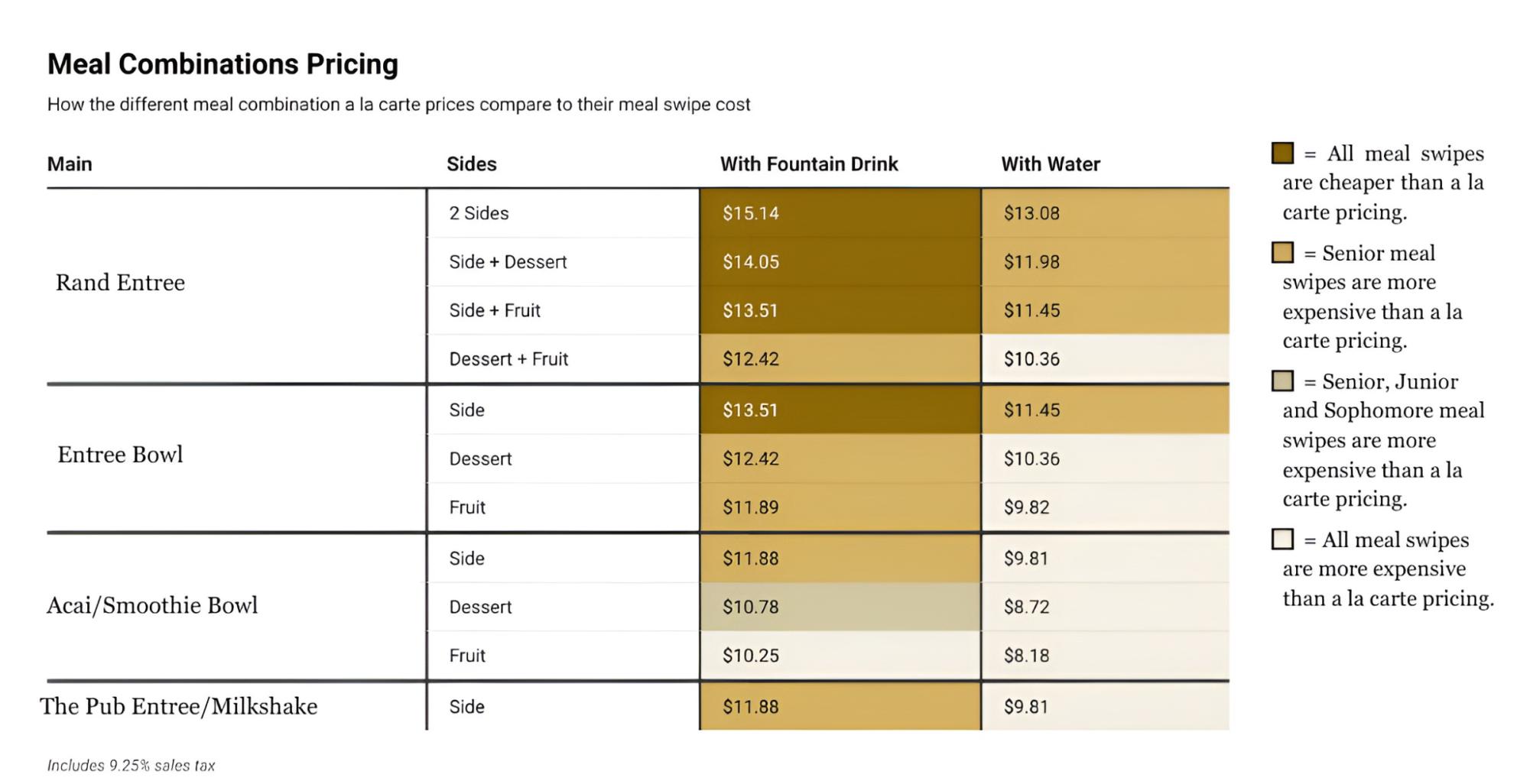

At retail dining halls like Rand and The Pub, items are priced on an a la carte basis as well as being available for a meal swipe. When we compare what you can get for a meal swipe with the cost of a swipe, it becomes clear that Vanderbilt is forcing students onto meal plans that are excessively expensive.

(Chloe Whalen)

At Rand, there are only a few options that are cheaper on a meal swipe than paid with real money. Some combinations, such as the smoothie, fruit and fountain drink at 2301 total less than even the First-Year meal swipe’s cost. At The Pub, there is no meal that is ever cheaper for seniors on a meal swipe than al la carte. In these locations, most meal swipes cost more than the items you can get for them. This situation is especially true for students who prefer to drink water since they wouldn’t pay for a fountain drink. So to those who prefer an apple to french fries or water to orange juice, you are likely overpaying for your meals.

In specific circumstances, it is possible for students to save money using the meal plan compared to a la carte purchasing; however, this solution would require students to maximize all of their meal swipes, which often doesn’t happen. Regardless of grade level, students who don’t use all of their meal swipes, eat smaller portions or prefer cheaper meal combinations would likely benefit from ditching the meal plan and paying per item.

Most despicably, Vanderbilt not only mandates the number of meal swipes we must purchase, but also how we can use them. A few years ago, a group of students started Swipes for a Cause, a way for Vanderbilt students to donate their excess meal swipes to food banks. However, Vanderbilt quickly and forcefully shut down this program, citing cybersecurity concerns. Later, the university launched a significantly restricted version where students could only donate their extra guest swipes — a maximum of five per semester. Instead of allowing students to use their pre-paid swipes how they wanted, Vanderbilt deployed the Office of Student Accountability to obstruct students’ charitable efforts, leaving the swipes unused. Any unredeemed swipe results in Vanderbilt retaining that revenue without having to provide a product or service.

Typically, bulk buying constitutes a reduction in the price per unit of an item, but at Vanderbilt, the individual items are often cheaper than the bundle itself. Vanderbilt can only impose this backward system because of its monopoly power. If students had a choice, many of us could continue eating the same meals we always do for significantly less money.

Looking Forward

Students come to Vanderbilt first and foremost to receive a world-class education, but the university has taken advantage of this aspiration by bundling a bunch of extra costs into attendance. If you want to attend Vanderbilt and receive the education it promises, you need to pay for tuition, overpriced housing and obscenely expensive meals. While charging exorbitant prices may not be unheard of at other elite universities, that does not make this practice right.

Students are limited in our ability to fix these problems since Vanderbilt writes the rules. The best thing we can do is consistently push back on these injustices. Speak out against pricing inconsistencies, maximize your meal swipes and donate excess food through channels Vanderbilt hasn’t banned yet. Respond in the way that makes the most sense for you and your financial situation. While students can take small steps to improve their own situations, responsibility falls on those leading Vanderbilt to right these wrongs at the institutional level. Vanderbilt’s motto, Dare to Grow, calls on us to continuously improve. The best way for the administrators to display this commitment to growth isn’t just to invest millions into new athletic facilities or choke campus with endless construction projects. Instead, they should ensure that students are paying a fair price before they try to finance their next major project. Only then will we dare to grow into a truly better institution.