I have recently felt an overwhelming inclination to meticulously comb through my Instagram followers and one by one remove each person whom I do not personally know — or at the very least, could not hold a conversation with today.

I have begun this process several times, unfollowing and removing followers by the dozens. However, merely minutes in, I get exhausted with the individual assessment of my relationship with each follower, and too often settle with the conclusion, “well, I guess I kind of know them.” Occasionally, I’ve resorted to simply temporarily deactivating my account. Other times, I’ve considered deleting my Instagram account entirely, thinking of starting fresh with my upgraded standards of establishing only meaningful online connections. But, the thought of having to repeat this task on each of my social media platforms is even more daunting and discouraging.

My vehement distaste for social media as it deviates further from reality is hardly surprising given how the online world has corroded our post-pandemic relationships.

The surge of TikTok — right at the cusp of the pandemic — propelled us even further into the digital society that is rapidly overtaking our healthy practices of human interaction. We’ve retweeted, snapped, streamed and reposted ourselves into an alternative universe. Since March 2020, Americans aged 18 and over have spent an estimated 1.43 billion hours on TikTok alone. The coupling of forced physical isolation with a global platform that provides entertaining and addicting 30-second interactions made for great social convenience as well as an imbalance between our online and offline worlds.

Globally, there are 4.9 billion social media users. The average user actively interacts on six to seven platforms, and Facebook leads with over 3 billion users. We encounter hundreds of strangers every single day on multiple different platforms. With every interaction, our digital societies widen our individual perception of the world at an exponential rate, damaging healthy standards of human interaction.

It is not only the sheer number of online social interactions we’re having that I find concerning, but the lack of depth in each interaction. This overexposure to minuscule communication is minimizing our ability to maintain the meaningful in-person relationships that are essential to our overall well-being.

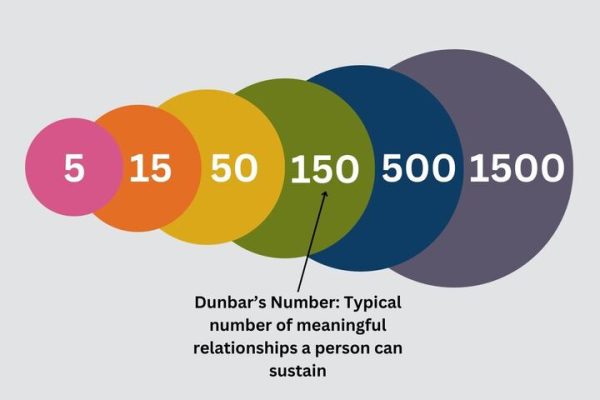

I spoke with University of Oxford psychologist and anthropologist Dr. Robin Dunbar, who coined “Dunbar’s number” — the number of stable, meaningful relationships that humans can possess and maintain is 150.

Dunbar’s model suggests that a person should have five close friends, followed by a “sympathy group” of about 15 people, an active or close network of about 50 people and an extended personal network of about 150 people. There are, however, two additional outermost layers — or “weak ties” — of 500 and 1,500 people. The inner layer represents the number of people we know well enough to have a conversation with and the outer layer represents the number of faces we can simply identify. The outer layer is where online connections, parasocial relationships and “influencer” followings generally fall.

(Lexie Perez)

The age of digital society has shattered Dunbar’s cognitive limit theory. Only 25% of Instagram users have below 1,000 followers, and 50% of users have between 1,000 and 10,000 followers. On a single platform, the ease of following people allows us to push these outermost limits with superficial online connections.

“You get the same patterns whether you look at it as face-to-face interactions, telephone calls, texting, or social media,” Dunbar said in our interview. “The online world is constrained by the same problem that really constrains our face-to-face social world: our minds and our ability to manage relationships.”

We like to imagine that our online and offline worlds are entirely distinct from one another, reassuring ourselves that what we expose ourselves to online will not negatively infiltrate our everyday lives and relationships. We spread ourselves thin by aiming to maintain myriads of relationships — both online and offline — of varying significance. Before we have established 150 meaningful connections or even 500 connections with whom we can comfortably converse, we have already far surpassed 1,500 merely recognizable individuals. Dunbar explained in “Science” that to maintain group cohesion, individuals must be able to satisfy their own needs, and we need to, in some sense, physically exist alongside each other in order to manage a stable community.

We attempt to maintain group cohesion in our digital societies through means such as comments and reposts. This is how we uphold our individual role and input, and prove our investment to the group. We partake in social media activism rather than physically organizing our greater community around the issues. We dedicate hours to engaging in debates in the comments section rather than having substantive open dialogue with our peers around campus.

Out of fear of missing out, we convince ourselves that we need to post to stay involved and to keep our followers constantly updated. Then, every so often, we inevitably make attempts to restore Dunbar’s order in our interactions. We feel an overwhelming urge to temporarily deactivate our pages, to archive posts, to “BeReal” and to activate secondary and more private “spam” pages. We don’t like feeling too seen and perceived. We instinctively yearn for smaller circles. Dunbar’s number suggests that there is, after a certain limit, an adverse effect to exposure.

“Being exposed to too many people makes you very dissatisfied with your current relationships,” Dunbar said.

Prioritizing close, meaningful relationships is not only essential for social functioning, but also for our individual well-being. Dunbar said much of his research has shown that there is a positive correlation between the extent to which someone deviates from the levels of acquaintanceship and their future probability of having symptoms of depression.

“The best predictor of your psychological, mental and physical health and wellbeing — and even how long you’re going to live into the future from this particular moment — is the number and quality of the close friendships [and family relationships] that you have,” Dunbar said.

Rather than serving as an ideal alternative world, social media should be used to preserve the meaningful relationships we established in person. No matter how normalized online communication becomes, in-person connection cannot be replicated.

“The layers of the network require you to see someone on a very regular basis. If you don’t see them at that frequency, the relationship will inevitably decay quite quickly,” Dunbar said. “What social media clearly does is slow down that rate of decay; but it doesn’t stop it. If you do not at some point reconnect face-to-face, nothing is going to stop that relationship from decaying.”

In a quest for balance, we can consciously choose to maintain the sanctity of our circles, valuing quality of friends over quantity. Social media can broaden our knowledge of the world and diversity of thought, but so can engaging with peers on campus, attending cultural events with friends or taking challenging classes. We can aim to keep our minds open while shrinking our online communities. We are most impactful right here in our own bubbles.

As we grow out of our college campus, creating lasting connections will become increasingly more difficult. We should be consciously prioritizing forming meaningful relationships while it’s relatively easy to do so. We should be learning how to form stable networks and gain social awareness, skills vital for our personal and professional futures.

“At the end of the day, the real friendships that matter are the ones that you literally can cry on the shoulders of,” Dunbar offered as a final note. “That means you have to be able to walk around the block, knock on their door and say, ‘I need to talk to somebody.’”

Many of us have likely fallen into a routine of starting our day with a scroll on Instagram and ending it with a scroll on TikTok. Rather, we could aim to abstain from social media as we begin and end our days, opting instead to offer our roommates a “goodmorning” or “goodnight.” We can set screen limits to our most addictive platforms and strive to intentionally engage with one another face-to-face, utilizing social spaces such as residential common areas and dining halls.

We must not let our online interests diminish the value of true, meaningful relationships, especially as college students.