If there’s one weekly routine I can count on, it’s the all-out melee on Friday evenings as my friends and I settle on a local restaurant — often one part of the Taste of Nashville — at which to dine.

It’s a remarkably consistent demonstration of politics, negotiation and warfare of a fervor unrivaled by any classroom debate. Some of us are partial to Satay and Sitar, hungry for a bit of spice. Others comfortably flock back to Nicoletto’s or Roma, knowing the warm embrace of Italian cuisine (see: chicken parmesan) is difficult to deny. But one restaurant always seems to climb its way to the top of our list: Hopdoddy Burger Bar.

This outcome, unfortunately, is a devastating loss in my book. Indeed, it’s become something of a joke in our clique: If you want to see Parker at his lowest, just ask if anyone wants to hit Hopdoddy for dinner tonight. Comedian that I am, I tend to lean into the bit for a cheap laugh. Haha, burgers again, very funny…

But deep down, my distaste for Hillsboro Village’s premier burger bar goes beyond an inside joke. It touches on a trend that has been the subject of much debate in culinary spheres across the country, a trend that has recently begun to bother me more and more — like a scrap of food caught between my teeth.

Everything on the menu at Hopdoddy is big. Too big.

If you’ve ever been to the burger joint, as I suspect many fellow Commodores have, you know what I’m talking about. If you don’t, a brief tour through Google Images will suffice. Burgers taller than they are wide, stacked to glorious altitudes with as many as three patties. Thinly-cut truffle fries served in bowls big enough to host the NFC Championship. And, of course, the iconic glass goblets filled to the brim with craft beers and ciders, better suited to a king than a computer science student like myself.

On the surface, a burger, some fries and a drink seems like a perfectly satisfactory meal. Hopdoddy doesn’t mess around either; everything they serve is of respectable, even commendable quality at a price that isn’t unreasonable for Tennessee’s most expensive city. In fact, if the burgers were a fraction of the size, they would leave me little room for complaint. But the sheer magnitude of the feast delivered to my table on that little silver tray somehow surprises me every time, leaving me with a guilty conscience and too many leftovers.

Turns out, Hopdoddy isn’t alone in letting customers bite off more than they can chew. Portion sizes have been growing in volume since the 1970s, according to NYU researchers. Researchers at UNC broke the trend down even further, analyzing growth in portion sizes by category. Hamburgers were a notable offender: Between 1977 and 1996, the typical burger grew 23% larger. But hamburgers aren’t even close to taking the top spot; the average plate of Mexican food grew by 27% over the same time frame, while snacks and soft drinks reigned supreme, growing by 52% and 60%, respectively.

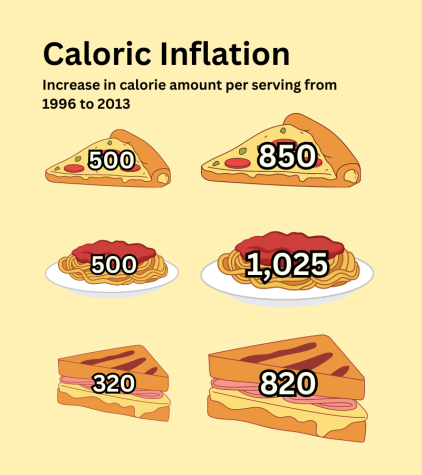

But the gigantification of food didn’t stop in ‘96. In fact, the NIH reported continued caloric inflation over the next two decades after the UNC study had ended. Two slices of pizza went from around 500 calories to 850. A plate of pasta jumped from 500 to 1,025. And the typical turkey sandwich? It more than doubled its stats, going from around 320 calories to 820. Surprisingly, burgers actually experienced fairly low caloric inflation during this time period – only around 77%. But they have more than doubled in size since 1977, as have most other foods analyzed in these studies.

My personal experiences in Nashville and elsewhere offer anecdotal evidence that the trend has only continued over the past few years. Whether it’s Pancake Pantry’s colossal stack of four flapjacks, Elliston Place Soda Shop’s three-egg omelet that easily clocks more than three eggs or the 30-ounce Trenta size offered by Starbucks for beverages that traditionally would be less than a quarter of that volume, it seems like a lot of restaurant food and drinks are just really, really big.

“Portion distortion” is the pithy name dieticians have given this phenomenon, and it’s rooted in simple psychology and economics. Restaurant-goers want a good meal, but they also want to get it for the best value. Rather than cut prices – which is historically difficult – restaurants tend to put more food on the plate, offering up more bites for your buck. This approach is great for grocers selling food meant to last a week or more. But for dine-in restaurants, where food is prepared and plated to be eaten within the hour, this approach intuitively forces customers to choose between wasting food and eating more than their fill.

Neither of these outcomes is ideal. Feeding America reports that 40% of all food in America becomes waste, 61% of which is generated from commercial outlets like restaurants. That equates to 119 billion pounds of commercial food waste annually, nearly 700 times the weight of the Titanic. All those pounds translate to 130 billion plates of food, more than enough to give the 34 million Americans facing hunger three square meals a day. Even at Vanderbilt, uneaten food piles up on dining hall dish returns and in trash cans. A 2017 event hosted by Students Promoting Environmental Awareness and Responsibility (SPEAR) collected nearly 600 pounds of food waste from Commons in a single day.

But let’s say I’m dedicated to cleaning my plate. Waste not, want not, after all. Turns out, over 90% of meals offered in restaurants exceed suggested calorie thresholds for a typical meal. People are also more likely to eat more when more food is given to them; our eyes are almost always bigger than our stomachs. The natural consequence is a steady contribution to an already critical obesity epidemic: Around 40% of people in the U.S. were obese in 2017 according to the CDC. And almost every study has discovered statistical significance between the growth of portion sizes in American restaurants and the increasing prevalence of obesity over the past 50 years.

I want to be clear: I’m far from one to criticize what people are eating. I grew up on a daily breakfast of unfrosted cinnamon Pop-Tarts. I’m still struggling to kick a potato chip habit that once saw me destroy a family-sized bag of Lay’s Lightly-Salted in an hour and a half. Besides, people have different dietary needs based on age, sex, activity levels and a million other factors, as well as different options and levels of autonomy in choosing what their meals look like. Some people just want leftovers for the next day’s lunch. My beef isn’t about what people are eating.

It’s about what restaurants are serving.

We often joke about the haughty Michelin restaurant that serves an avant-garde, bite-sized plate of Wagyu steak topped with caviar and flakes of gold, charging four figures for the caloric equivalent of a bag of baby carrots. Small plates are derided as pretentious, overpriced and unsatisfying. No wonder restaurants present us with such a bounty; inevitably, many customers would riot if the size of their servings were reduced.

But some of the best things I’ve ever eaten have been small. Authentic, flavorful and delicate tacos at Mas Tacos Por Favor. Perfectly seasoned sides of grilled asparagus and brussels sprouts from Barcelona Wine Bar. Even sushi – I’m partial to the O Roll at I Love Sushi, but almost any sushi checks this box. A big plate of food derives its value to customers from being big. A small plate of food is forced to achieve value by being artistic, unique and delicious.

My friends will read this and chuckle. If I’m lucky, I might delay our next trip to Hopdoddy for a couple weeks, or even until next semester. But the truth is that Poke Bros, Frutta Bowls and the Grilled Cheesery will always have my heart for serving something just as tasty in half the size. I think Nashville, and probably every city, could use a little more of that.

Until that day, I’ll order half portions. I’ll ask for takeout boxes rather than leave anything behind. And I’ll skip the sides, even when it hurts. For me, when it comes to food, less is often more.

Who cares • Apr 20, 2023 at 11:54 am CDT

Who allowed this article to be posted ? who complains about bigger portions? Want less food? Order less

thx for sharing • Apr 17, 2023 at 4:56 pm CDT

okay???