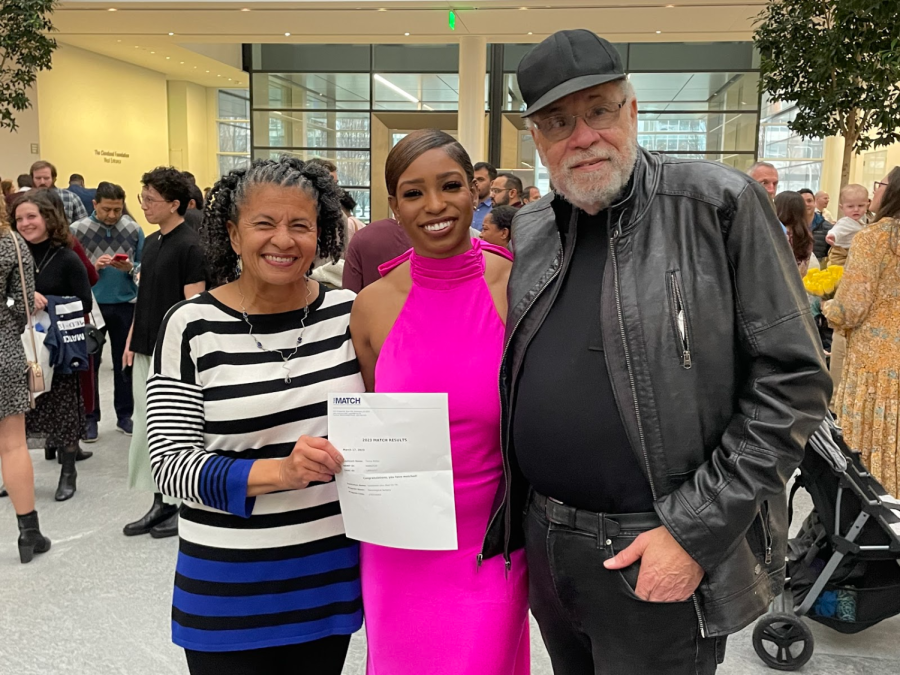

Match Day 2023 marked an important milestone for nearly 35,000 aspiring physicians across the country. But one made history here at Vanderbilt. If you spent even half an hour on Instagram on March 17, chances are you saw the many viral reels of 26-year-old Tamia Potter matching with VUMC, making her VUMC’s first Black female neurosurgery resident since the hospital’s opening in 1874.

A Tallahassee, Florida, native and the daughter of a military father and nurse mother, Potter is a proud third-generation alumna of Florida A&M University, an HBCU. Since she was a child tagging along on many of her mother’s workdays — playing with anatomy labs and models, Potter knew her heart lay in medicine. After graduating from the very university where her parents met, Potter was admitted into Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine where she has produced 12 research papers.

Potter envisioned VUMC as her future home from the moment she arrived for her “away rotation” — a process that medical students complete before residency applications by spending a month at several of their prospective medical facilities. With its welcoming and attentive staff, VUMC easily stood out against her other location interests. When it came time to rank her residency choices, she knew the institution had earned her top spot.

“When I got to Vanderbilt and met those residents and the faculty and attendings, I fell in love,” Potter said. “I didn’t feel out of place. That’s what stood out to me about Vanderbilt. When you’re a Black woman in medicine, you feel it. I did not feel like I was treated any differently for the color of my skin or for being a woman. Being a woman in surgery is very hard as well, but I felt no difference. I had not had a feeling like that anywhere else, and the tone was set like that from day one. It didn’t change.”

(Tamia Potter)

Potter also favored VUMC largely because of its location in Nashville. She appreciated the workplace’s Southern hospitality and saw the hospital as the most fitting location to happily spend a seven-year-long neurosurgery residency.

“I am a Southern girl — I want to give back to the South,” Potter said. “I cannot be anywhere else but the South. Also, when people think about neurosurgeons, they think about very mean people who don’t talk to anybody and are really strict. The people at Vanderbilt were so welcoming and warm, and they treat you like family.”

Potter had a long journey from her initial medical school enrollment to Match Day. She says the match process for medical students is very lengthy and taxing.

“For neurosurgery, most people apply to around 80 to 100 programs,” Potter said. “I applied to 65 programs and I got 40 interviews. You just physically cannot do 40 interviews. So I canceled interviews down to around 27, then I got really tired and just did 22 interviews. They’re from like 8 a.m.-8 p.m., but some last two or three days long.”

Holding the weight of being a trailblazer isn’t new to Potter — she said she’s grown up being the only Black girl in the room. In addition to being the first Black student body vice president of Wakulla High School, she was also the first Black person on the school’s Honor Court and the first Black Miss Wakulla County. Her ambitious high school successes extended into her early medical aspirations as well. Potter earned her Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) license at age 17 and landed her first job working in a nursing home in high school. With a full-ride scholarship to FAMU, Potter majored in chemistry and minored in biology while also working a full-time night shift at the hospital as a CNA.

“There are a lot of stereotypes about Black people in medicine and affirmative action,” Potter said. “People believe they’re sacrificing quality for quantity of diversity. That’s not the case. You can be a very well-qualified person and be a person of color at the same time. The problem is, because that stereotype exists, when you’re a Black person in spaces like these, you feel the pressure and need to be the best because you want to prove to people that it is not an affirmative action job. I am qualified to be here, and you’re not sacrificing anything by me being here.”

There are over 100 medical specialties, but deciding on neurosurgery wasn’t difficult for Potter. She said she’s always had an inkling toward the physiology and anatomy of the nervous system.

“I think it’s very interesting to be able to understand how I’m having this conversation with you, which parts of the brain are working right now, what happens when they dysfunction and how to fix it,” Potter said. “I like the problem-solving that comes with neurosurgery. Working with a system where you have little room for failure really drew me to [neurosurgery] because I’m kind of a perfectionist.”

Potter says her passion for neurosurgery also stems from her empathy for the patient population. Her ultimate goal is to make neurosurgery more accessible to people like herself while also ensuring she’s providing the highest quality of care to patients. She believes the U.S. is in a pivotal position for medical treatment, especially in neurosurgery.

“It’s 2023. There’s so much technology — like AI — that can be used to help treat patients,” Potter said. “There are ways that we can find to treat patients without breaking their pockets. A lot of these pathologies, people didn’t ask for. So it’s not fair to ask them to cough up half a million dollars for something that they didn’t even cause themselves. Something I really want to do is figure out how we can reduce the cost of treatment, but also make sure we’re adequately treating patients with the highest quality of care.”

There are currently 33 Black, female neurosurgeons in the U.S., encompassing 0.585% of all neurosurgeons. Potter emphasized that, while some may criticize VUMC for taking 150 years to add to that percentage, this situation isn’t unique.

“This is normal,” Potter said. “Gabbie Johnson, she’s in my class, just became the first Black woman to train in neurosurgery at WashU. Most of these places have not trained Black women before.”

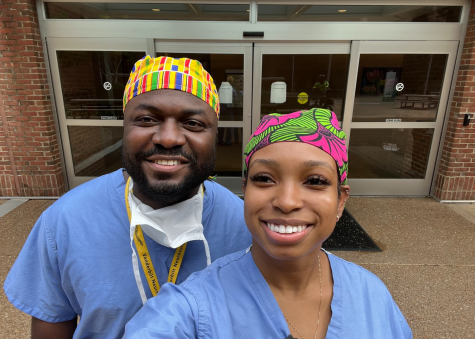

Potter also pointed out that VUMC’s current first-year neurosurgery resident Kwadwo Sarpong only had a handful of Black men precede him as well.

(Tamia Potter)

Potter encourages undergraduate students to follow through with their medical school aspirations, no matter the educational hurdles which may arise along the way. She even attested that someone looking at her own MCAT score years ago probably would not have predicted she’d be in the momentous position she’s in now as a result of her steadfastness.

“You don’t know what someone is capable of until you give them the right resources,” Potter said. “You can’t just say because this person came from this school and because they don’t have these scores that they’re not going to be an amazing doctor and surgeon.”

Potter wants to educate people on the many pathways to and possibilities within medicine. She has plans to work with both the American Society of Black Neurosurgeons and Women in Neurosurgery to spread awareness for increasing accessibility to neurosurgery. Potter also wants to use her position to be a symbol for other aspiring physicians.

“I didn’t see my first Black female neurosurgeon until I was 21 years old when I’d moved to Case to start med school. That has to change. Everyone isn’t cut out for everything, but at least you can see it. At least you know it’s a job option and it is attainable. It may be hard, but it can still be done. That’s what I want for neurosurgery,” Potter said. “It is doable if you have the right tools and the right resources and mentors.”

While VUMC is excited to soon welcome Potter to Nashville, she is far more excited to satisfy her own Southern longings. Having attended medical school in Ohio, she feels deprived of the sunshine and cuisine of the South and her home state.

“I am ready to be in the South! I want food, music and sunshine,” Potter said. “I want fried chicken, collard greens, candy yams, cornbread and macaroni and cheese baked with the crust burnt on the side. I’m ready to say ‘yes ma’am’ and ‘no ma’am’ and not have people look at me like I’m crazy. I’m ready to be around people who understand me and know exactly what I’m talking about when I say I want some grits.”

If the long hours of her neurosurgery residency dare allow it, Potter hopes to cheer on Vanderbilt at a few home basketball games in the future. As she closes her studies at Case Western, the Commodore family sends her our best wishes and proudly awaits her July arrival.